By Thomas Moore

As I’ve been writing a book about sex in recent months, I’ve had the Kama Sutra , the Indian guide to personal sexual culture, spread out on my desk in front of me, and occasionally I’ve consulted the Internet to track down relevant books and articles. On the Internet, I’ve noticed, as soon as you venture in the direction of sex you quickly come upon graphic images showing crude, unadorned forms of stark sexual union. Apparently we have finally found a public place where we can show our private parts and secret fantasies, free of the repressive eyes of governmental agencies in service of the puritan philosophies that dominate our culture, but here there is no love, little sentimentality, and almost nothing that could be called foreplay in any innocent sense of the word.

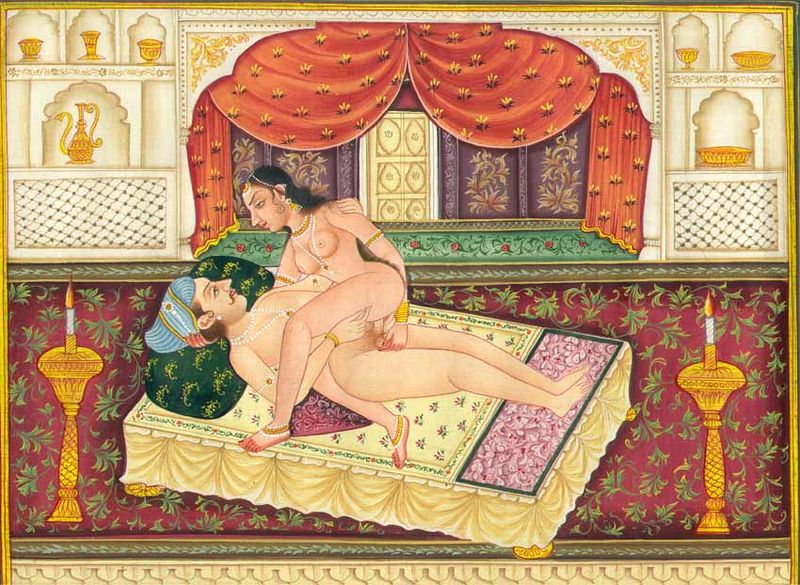

In contrast, the Kama Sutra discusses a wide range of sexual matters, beginning with the general comportment of one’s life (dharma), establishing personal economic security (artha), and the arts of love (kama). I notice that the Kama Sutra, graphic and open-minded in its own way, places sex within the context of a refined humane life, while the Internet focuses on organs and acts.

I’m reminded of the beautiful erotic figures carved into the Indian temples of Khurajaho and Kanarak over one thousand years ago, images that depict every imaginable sex act within a context of worship and prayer, and I wonder why the Indians put their sexual fantasies on temples while we give ours over to pornography. This is one of those questions that I believe, if we could answer it, would pinpoint exactly what’s wrong with our culture.

Although I’m convinced we’re all moralists at heart, I’m not interested in making any judgments here about the ethics or appropriateness of the Kama Sutra, the temple sex couples, or the Internet, but I am interested in the sexual life of the community I live in. We seem to be both obsessed with sex and embarrassed by it. Sex sells, I’m told by almost everyone who hears I’m writing about the theme. Some insinuate that I must be writing about sex for the royalties alone, cashing in on our mass compulsion, but I wonder if I’ll lose readers, because one isn’t supposed to be interested in both spirituality and sex unless you’re writing about sacred sex, whatever that is, or offering suitably cantankerous health or moral cautions.

Medieval monks spent hours at their holy work of copying manuscripts containing chapters of the Bible and lessons in grammar, while in the margins, called gutters, they doodled all kinds of obscene images and phrases. We do something similar when we create an efficient, clean world of speedy highways and no-nonsense office buildings, while our extravagant sexual images — our dirty thoughts — are funneled into red-light districts, a Forty-Second Street or a Hollywood and Vine, or an unregulated highway called Internet. We divide sex from ordinary life and then wonder why it enjoys emotional autonomy in our lives.

History shows that sex has always had its selected areas of tolerance and was rarely visible at the center of daily commerce, except perhaps in Pompeii or in the sacred precincts of old Greece, Peru, Rome, and Sodom and Gomorrah. I’m not arguing for a democratization of sexual images, because it seems appropriate to be as careful about sex in public as a parent might be about it at home, but I do wonder about the sharpness of the line drawn between public life and the gutter. I wonder why we demand that our political leaders be without sexual fault — I discovered while practicing psychotherapy that no one, least of all our upright fellow citizens, lack lurid skeletons in their closets or in their dreams and fantasies.

Maybe if we spiced our daily lives with qualities associated with sex, we might make public life more sensuous and the gutters classier. People used to build beautiful, sexy bridges, for instance, but now we build them for cost-efficiency alone. People used to build roads that you’d want to drive on for a Sunday outing, but today we just want to get from one place to another as quickly as possible-no foreplay. Today we don’t have time, anyway, for a Sunday drive. In some parts of the world, say in a piazza in Rome or a plaza in Mexico, businesses fill the square with chairs and tables decked out with food that would make you salivate as you pass by. In some parts of the world they still make life itself sexy with their sensuous movies, their extravagant food, and their seductive streets. We have our oases of public sensuality-Bourbon Street in New Orleans and maybe the casinos of Los Vegas-but usually they are so removed from the culture at large that they quickly become outrageous and tinged with unsavory — a telling word-associations.

I look in vain in public areas for a good chair. Many crowded areas have no place to sit down, or if they do, the seats appear to be designed for something other than the human body. Sitting on a concrete slab, a popular form of public seating, doesn’t do much for my sexuality. My body would also like to see some nourishing color in place of the ubiquitous metallic glass, an overabundance of flowers and trees instead of an architect’s skimpy afterthought-the token juniper and de regueur marigolds, and sensuous flowing water that isn’t hidden behind warehouses and bridge supports. I hope it’s obvious that food, flowers, seats, colors, and waters have something to do with sex.

Office buildings are often the most sexless places in public life. Our fantasy of work seems to translate into hard marble, cold granite, pale walls, authorless art, green-only vegetation, scarce windows, white light, modular desks, thin carpets, and bodiless background music. It’s no wonder that Eros takes advantage of the office affair as often as possible; it’s his only refuge. Here I find a rule that has broad application: Take sex out of the world we live in daily, and it will become a giant, unsettling force in our personal lives.

Religion has a powerful influence on sex in America, but the religious institutions merely reflect an attitude toward spirituality that is deep in the American psyche. Spiritually we are virtually all believers in transcendence, imagining our values, vision, inspiration, communal and marital cohesion, and faith all coming from above the clouds, off the earth, out of our bodies, far from sex. We believe in the mind, and we don’t trust the body. So far do we separate spirit from body that we are profoundly unsettled when we hear about a priest, preacher, or guru caught in some sexual scandal-it’s an old theological idea that humanity has nothing to do with divinity. We are working up a fever making new laws about touching each other in school and in therapy. As many have noted, we’re more scandalized by a photograph or painting showing a nipple or a penis than by the image of a child starving on a dry, dusty road or lying shot in the middle of a bombed-out marketplace.

The body is our central embarrassment-merely having one, making love with one, or indulging in the human fascination for the sexual body. To all appearances, we’d like to be bodiless, and most of our inventions point toward that goal as they encourage us to sit in front of a screen and work, play, shop, and meet with old friends electronically. But after a lifetime of avoiding the body, we meet it face to face in illness, where, not coincidentally, we also discover our souls. Illness teaches us lessons our high-tech education has overlooked: that we are mortal, that we have a body, that to be human is to have sensation, and that we could discover what is really important by paying attention to the body’s reactions. I suspect that we could learn all these lessons more pleasurably by living every day less mentally and more sexually.

The repression of the body and its main work, sex, wounds the soul immeasurably and deprives us of our humanity. Often we refer to sex as “physical love,” the work of a soulless body, and then we try to justify this biological act morally by making sure that it’s in the service of affection. But the bifurcation of body and soul can’t be healed so easily. We have yet to discover that sex is not physical love but the love of souls. You don’t have to spiritualize sex to make it valuable, because by its very nature sex is a deep act of the interior life and always brings with it a wealth of emotional and spiritual meaning.

Mircea Eliade, the religion scholar, often remarked that the sacred sometimes lies camouflaged in the mundane. As a student of world religions myself, I notice that the positions and organs one sees on the web’s erotic pages are identical with the positions and organs beautifully and graphically portrayed on the Indian temples, on Greek pottery, in ancient ritual, and in religious legend and lore. Oddly, pornography is so close to religion that one wonders if it isn’t at root an unconscious attempt to preserve the sacredness of sex. Where do you find graphic sexual imagery today? In pornography, in religious ritual and statuary, and in dreams. If we assume that dreams portray the soul’s interests in pure form, untainted as they are by conscious manipulation, then they tell of the psyche’s necessities and the role of erotic feeling and fantasy in the economy of the heart. Religious erotic art shows us how profound sex is in the nature of things, and how close to religious ecstasy is the pleasing oblivion it grants. Pornography plays the role of providing a symptomatic presentation of erotic realities that have been excluded from our canons of propriety.

We have lost religion, not as an institution or a set of beliefs, but as a way of living close in touch with the raw roots of desire and meaning. With religion absent, sex, historically wedded to religious practice, falls into the gutters, as much outside of life as religion but now shaded in darkness. Potent sexual imagery has been removed from public life, appearing only in graffiti and in taboo magazines and movies. Artists, always intimate with religion, intuitively perceive the close relation between sex and religion and try to give eros a prominent place in their work, but since art, too, has been marginalized, we misjudge sexual imagery in art as irreligious and pornographic.

Sex is trying to break through and out of our secularism, but we misread the signs, thinking we’re beholding the work of the devil instead of angels. Pornography is the return of the repressed, the religious nature of sex presenting itself in dark instead of bright colors. Every time we think of sex as biological, every time we teach sex education as a secular study, we are setting ourselves up for more pornography, and, strangely, for all its stupidity, lack of taste, and outrageousness, as a symptom pornography both reveals and distorts the role of imagination in sex. Pornography is full of problems, but mercifully it keeps sex from becoming the heartless preserve of the medical establishment and the social scientist.

Sex is the ritual recovery of vitality and life. It makes marriages, creates families, and sustains love. It takes us momentarily out of our minds and into our souls. In sex we “come”-come back to ourselves in unmediated sensation, come back into our world from our mental outposts, and come back into life from our attempts to get a perspective on it. It’s no wonder we’re obsessed with sex, since it is the very epitome of vitality, and yet, because it is full of vibrancy, we’re also deathly afraid of it. We can all agree intellectually with John Lennon that life is what happens when you’re making other plans, but still we’d prefer the fulfillment of our plans to unexpected outbreaks of vitality. Unlike many other cultures, we don’t appreciate orgy, even within strict ritual limits. We leave it for pornography, where it is either indulged compulsively in the way of a spectator, or moralized against, or both simultaneously.

The most common story I have heard from persons in psychotherapy tells of a happy marriage in which one or two of the parties feel compelled to engage in an extramarital affair. The person involved can’t understand the reason for the overwhelming allure of yet another carnal liaison. They assume something must be wrong in the marriage or in their own past. They never consider that there might be some deep need for orgy, for sex without the weight of moralism, or for enough and varied sex to offset the bodiless, passionless life that modern work and family values insist upon.

In many cases, the affair looks to me like the office flirtation and the pornographic photo — it’s symptomatic of a failure to give sex enough prominence in daily life and in the privacy of a marriage. I don’t advocate affairs, but I can understand their allure in an age of incessant labor, anxious leisure, compulsive entertainment, unrooted ethics, and a public life built on efficiency and machinery. In this cool, gray world, we starve for friendship, excitement, and intimate conversation. One sought-after reward of an affair might be a forgetting of responsibilities, as the couple risk their reputations, marriages, and in some cases their livelihoods for a few wicked hours of carnal delight.

Some, of course, would say that affairs are the result of a breakdown in family values and traditional morality. Whatever the merits of the analysis, it is generally presented in a style and tone that are moralistic, self-righteous, paternalistic, and uncompassionate-indications of discomfort with sex and with the moral complexity it may bring into the lives of ordinary people. It’s difficult to trust an approach to life’s most fascinating and challenging mystery that demonizes sex or deals with sexual problems without heart.

One solution to our obsession/repression pattern in sexual attitudes would be to align sex with our intelligence, civility, spiritual values, and all other aspects of our daily lives. In the realm of the psyche, it seems that the segregation of any element leads to trouble. If the only thing in life is your depression, then there may be little chance of being liberated from it. If money is the aim and purpose of life, then it will probably reveal its emptiness in due time. Sex makes important demands for privacy and secrecy, but if we cut it off from the fabric of life’s totality, it may begin to show itself as odd and even monstrous.

It isn’t enough to make easy intellectual deals with sex — “I’m willing to understand that my sexual feelings are basically good and normal, if you, Sex, are willing to leave me alone and let me live my life according to my plans.” A more substantive weaving of sex into life may be accomplished by softening the barriers between ordinary living and sexuality.

We might temper our moralistic approaches to food. If you want to feel guilty these days, eat an outrageously sumptuous dinner with friends or boldly go into a market and buy some food that someone in a lab coat has determined is bad for you. Few things in life are closer to sex than food, and yet we’ve gone too far in surrendering this ordinary pleasure to the medicine-haunted guardians of kitchen virtue. Or, in a culture that frowns on idleness, give yourself some completely unproductive time in a day. Excessive productivity is incompatible with an erotically interesting life because the senses get distracted by busyness and drivenness. Not spending your time profitably might be the best thing you can do for your sex life.

We might give serious attention to feelings and qualities associated with sex, such as pleasure, desire, intimacy, and sensuality, and give these very qualities a place in all aspects of daily life. We might take needs of the body into consideration as we build and arrange our world. We might give serious attention to our ordinary desires. Sex finds its way by means of desire, and it follows that if we were to live life generally in tune with our sexuality, we would give desire its proper place. Some would object that to do whatever we feel like doing is narcissistic and irresponsible, but taking desire into account is not the same as doing whatever we feel like doing. We are not sophisticated about desire, and so we tend to reduce discussion of it to absurd, simplistic, and obviously objectionable terms.

Every day desires spring up from the pool that is the human soul and source of life. Some are strong, some weak. Some often contradict others. Some are impossible to satisfy, some can be dealt with in a few minutes. The point is, desire serves vitality and ushers in new life. We can’t act on all desires. If that were possible, at this moment I’d be living in several states and countries. Some desires stay with us for years and may change somewhat as time goes on. In some cases, late in life we may find a desire fulfilled after many years of containment and experiment. Being loyal to desire, giving certain desires time to show themselves more fully and reveal how they might make their way into life is a form of sexual living. Broadly speaking, it is an erotic way of life.

We could learn from sex to live all of life more intimately. There’s something sexual, again in a broad sense of the word, in a warm neighborhood community. I will never forget the afternoon, shortly before we moved from Massachusetts, when our family gathered our neighbors together for a good-bye ritual. We created a small spontaneous ceremony in which we all said something from the heart about our history in the neighborhood and about the loss we were all feeling. This moment reflected an intimate way of living on a street. We could have kept our thoughts and feelings to ourselves, but the closeness of that moment represented the eros, the sexuality, of living among good friends.

Our society can be a friendly, helpful, and community-minded place, but in the area of sex especially it can hardly be called compassionate. Quickly we judge celebrities whose private sexual difficulties become public. We dispose of politicians and military personnel who miss the mark of our anxiously protected norms. Because sex is so full of life, it isn’t easy for anyone to deal with it, and it is rarely neatly arranged. In general, if we want to live a soulful life we have to allow some latitude for the unexpected in ourselves and others, but this is especially true of sex. It is the nature of sex, maybe its purpose, to blast some holes in our thinking, our planning, and our moralisms — sex is life in all its boldness; it’s not a hothouse of efficient repression.

Read the biographies of the men and women who have made extraordinary contributions to humanity throughout history. List their achievements in one column and their sexual idiosyncrasies in another. Notice the direct proportion between sexual individuality and creative output, between desire heeded and compassion acted upon. Then reflect long on your moral attitudes: Are they deep enough, humane, compassionate, and suitably complex?

Every day we could choose to be intimate rather than distant, bodily rather than mental, acting thoughtfully from desire instead of from discipline, seeking deep pleasures rather than superficial entertainments, getting in touch with the world rather than analyzing it at a distance, making a culture that gives us pleasure rather than one that merely works, allowing plenty of room in our own and others’ lives for the eccentricities of sexual desire, and generally taking the role of lovers rather than doers and judges.

© 2002, Thomas Moore

Amanda, when I first read your comment this came to mind: “the more fully human I become, the closer I come to god”. This has been my experience, and has been part of my path to getting in touch with my body, my feelings, my sensations, my ability to feel compassion for another, to feel awe and wonder at something miraculous, or to well up with joy when something touches my heart. All the things that make me human, and have brought me closer to god. Feeling god. The Great Mystery.

On another note, I have seen some really great art exhibitions at several of the Smithsonian Museums here, mostly at the Asian and African American Art Museums, that very much depicted sexuality and a sexual openness of the times, it’s seeming importance and relevance, whether male-female or male-male. I don’t recall much female-female depicted though, now that I think about it.

MoonRose

…as reverence for existence.

i agree — great article. i’ll have to read through it again when i have a little more time (hot outdoors — time to go play in some water!).

i find Moore’s thoughts about needing to be *closer* to religion, not freed from it, very interesting. i get the sense he’s using the term in a more spiritually whole and ideal sense than how most of us experience religion these days…

I really enjoyed reading this article — I read it in the middle of last night after stumbling across a reference to it in one of the posts above. It is well written and a worthwhile read.

Surely the time has come for us to take our minds OUT of the “gutter” (yays to the monks and their doodlings…..!) and instead throw Eros right back IN! It would be a freeing adventure I’m sure — I know that it’s something I need to dive in to. We are so conditioned to deny our bodies and desires cloaked as they are in fear and apprehension.

However, I sense a shift in attitudes, especially among young people. Just last week my friend’s thirteen year old daughter was explaining to her mum, in a casual matter of fact way, that her friend was bisexual. How refreshing to hear such honesty and acceptance and not a smidgen of sanctimonious judgment or condemnation. Our youth can show us the way “back to the garden” because they haven’t quite shaken off their stardust yet. I hope they never do, all the while reminding us that we are ALL golden and that together we are, as Thomas Moore suggests, “making a culture that gives us pleasure rather than one that merely works.”

Amen to that. Let the desiring and expressing begin!

I find considerable push-back from creative partners regarding the creation of sexual images that are also beautiful (beyond the fundamental concept that sex itself is inherently beautiful.) In other words, people love porn, but erotica is more difficult to “sell”.

Last evening I felt compelled to explore a simple idea I have noticed over a long time – that it has become difficult to feel. In this sense I mean this — there are few material things by which I am surrounded each day that I can actually feel more than superficially. Experimentation shows that I can feel the cotton sheets on my bed more deeply than I can feel the polyester blanket. I can feel the wooden table more fully than the plastic keyboard that I currently type upon.

I began awareness of this years ago with my cats. I had discovered that I was not really FEELING them, although I stroked their fur. I began to practice the art of sensitivity in a different way.

Last night I sat with a houseplant for some time – feeling its vibration so deeply……..this may be old news to lots of you out there, but I had never considered that this was something THAT NEEDED TO BE CONSCIOUSLY WORKED AT. That is, feeling at core/sexual level. That is, so much has been cut away as described in Mr. Moore’s article.

Well, nothing to conclude here, fellow PWers only that this article (once again, thank you PW) fits the moment beautifully – and expresses so much so eloquently. I have pulled many quotes from it to consider as I go about this day of mine, but this one seems so very basic to all – “that to be human is to have sensation”

So many ways to experience that today…..beginning with a cat who’s just come over for a scratch on her chin.

xo