First published Oct. 27,2016 Link to original

Dear Friend and Reader:

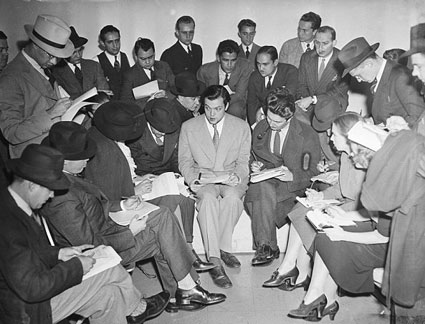

For his weekly program on Halloween eve of 1938, a young Orson Welles tried something new. For some months, his Mercury Theater on the Air had run on Columbia Broadcasting System (the CBS Radio Network) with a small listenership. On the evening of Oct. 30, they decided to try doing a science fiction program.

They had acquired the rights to a short novel written by the British sci-fi author H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds. (Wells and Welles were both of English descent, both had George in their name, but they were not related.) That story, about an invasion from Mars, had been published 40 years earlier, in 1898. It was an old and well-known work at the time, read by many children and recreated in comic books.

Welles, however, thought the story made a boring script, so his writers updated it into a series of spot-news reports about an invasion from Mars that cut into a seemingly ordinary dance music program. This was a new technique at the time, the earliest version of the “breaking news” stripe at the bottom of the CNN screen: interrupting regular programming for something more important.

At the beginning of the program an announcer said clearly that the show would be a dramatization of the novel. Then at about 40 minutes, an announcer again said it was a dramatization, and then finally at the end Welles said it was a Halloween prank. But that did not matter; the genie was out of the bottle.

Most people know the history: some listeners panicked, thinking it was an actual invasion from Mars and war with Martian robots. Others thought some other kind of air invasion had happened, having missed the bits about Mars. It’s true that a good few people fell for the dramatization and freaked out. I heard a personal story about someone whose relative was in labor in a Manhattan hospital that night, and was abandoned by the maternity nurses who decided to save themselves and left the ward.

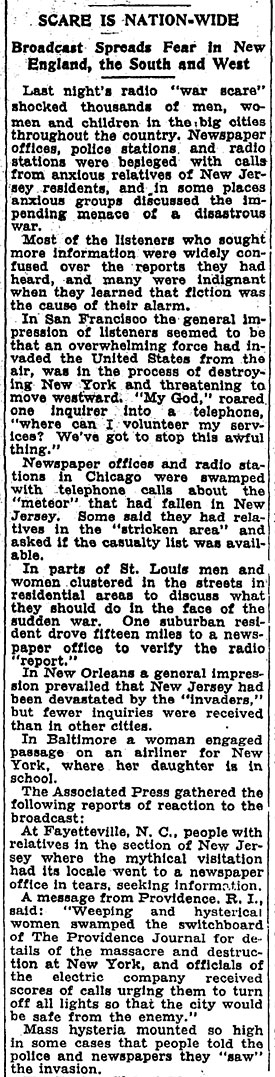

It’s true that many hundreds of phone calls came into the CBS switchboard, and hundreds of people called their local police stations all over the country. One guy in the Midwest was called desperate by a New York Times article the next day because he drove 15 miles to check in with the nearest police station; he must not have had an iPhone.

Then the newspapers ran with the story, greatly exaggerating how many people fell for the hoax. I’ve read that some 1,200 newspaper articles about the broadcast were published in the following weeks, nearly all of them focused on the supposed panic.

Introducing the Echo Chamber

What resulted was the first ‘classic case’ for media study, and what may have been the first example of the media echo chamber. Something started as a book, then became a radio broadcast. People took to the telephones in an attempt to verify whether it was real. Then the newspapers ran with the story, making it their own, and turning it into something entirely new.

By my reckoning, this was the first event of its kind, and provides lots to consider in terms of how we reckon reality against what we experience in the media. For example, the drama was not real; the panic was not as widespread as legend had it; but the panic was given substance when it was reported in print format.

Demonstrating that “the medium is the message”, this event had a different message depending on where it was published. Nobody paniced when the novel came out. They saved that up for the radio drama.

What we have is as much a study in the environment as it is a study in the event. The environment consists of radio itself, and of the state of mind of the listeners. World War II was unfolding in Europe as Hitler conquered countries one by one, so people were accustomed to hearing reports of a (real) war.

And the device of the news interruption of regular programming was happening so often that one contemporary commenter said the interruptions were getting interrupted. That’s exactly what happened the night of War of the Worlds.

We’ve been doing lots of media studies the past two years at Planet Waves as I’ve tried to get a handle on what this internet thing is all about. I’ve done some of this with the help of astrology.

I thought it would be fun to check out what was happening in the planets at the time of the War of the Worlds broadcast. There has been some excellent commentary written over the years; I’ll either weave it into the article or add it to the end as links for further reading.

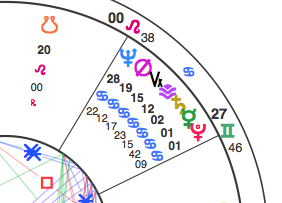

First, a Stunning Progression in the Chart of Orson Welles

Recently I introduced the technique of the progressed horoscope when reading the charts of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. If you want a more detailed description of the technique, I suggest the article about Trump’s chart. To sum up, progression is a method of casting astrology that moves the natal chart ahead one day per year. If you’re in your 42nd year of life, your current progressed chart is for sometime during your 42nd day of life. The astrological events of your first days on Earth parallel their corresponding years. It’s a strange phenomenon, but that’s astrology for you. It also sounds like the mathematical phenomenon of fractals.

A fractal is a sample of a mathematical pattern that contains the whole pattern. Discovered by science in the 1980s, my take is that the progressed horoscope is the actual discovery and practical application of fractals.

Progressions represent points of inner development that can come with corresponding events and developments in life. Most astrologers use them as a predictive tool.

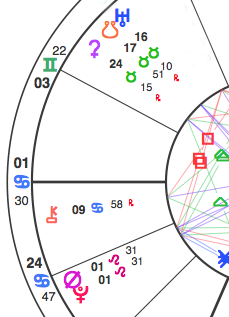

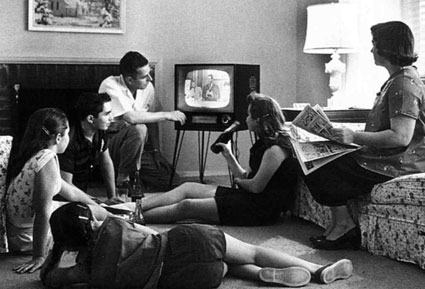

On the night that War of the Worlds was broadcast, Orson Welles was having an interesting progression: Mercury was conjunct his Pluto.

This happened just once in his life. Pluto was new at the time, having shown up in 1930, with many plutonian events coinciding with its discovery: mass media, the rise of fascism, another world war and fascination with sex, death and psychology. Pluto was the first astrological point openly associated with ‘the millions’. Mercury conjunct Pluto is shorthand for intense. Pluto gives that Mercury some serious impact, and profound, instinctual insight. The conjunction was located at the degree 1+ Cancer.

When the program began at 8 pm on Sunday, Oct. 30, 1938, that was the very degree rising. The rising degree of any chart is like the chart’s unique thumbprint. The rising degree moves fast, ticking by about one degree every four minutes.

It’s dependent upon location on Earth and time of day, and if you cast a chart for in the same place for every Sunday night at 8 pm, the rising degree will be different.

This was the one night that that one degree aligned with a rare conjunction by progression in Welles’s chart, about as likely as winning Lotto, or hitting jackpots on three slot machines simultaneously. And that’s approximately what happened.

The Aries Point is Everywhere

I’ve mentioned the Aries Point quite a few times — that’s the zone in the chart where the collective realm intersects with the individual realm. It’s described the Talking Heads line, “when the world crashes into my living room,” or by the Redstocking radical feminist collective — “the personal is political.” This is an extraordinarily important idea to keep in mind in these days in which we live: there is no private life that is not shaped or even determined by some much larger public life. We are part of the collective and it is part of us.

The Aries Point is the first degree or three of Aries; and by extension, the opposite degrees of Libra, and the first degrees of Cancer and Capricorn; in other words, the cardinal points. When the cardinal points are active, the portal from the individual into the collective is wide open. Also, the middle degrees of the fixed signs (the midpoints of the cardinal points) also give a dependable Aries Point effect.

Straight away, with 1+ Cancer rising, the Aries Point is in the game. With Welles’s 1+ Mercury and Pluto, that raises things by an order of magnitude. The Aries Point comes in different flavors depending on the sign involved. In Cancer, we get the feeling of home — all those people cuddled around their radios. Chiron in Cancer is rising in this chart, at 9+ Cancer (which adds emphasis: this is gonna be strange, so let’s get on with the show).

Opposite Cancer rising we have Vesta in the first degree of Capricorn. I’m not sure how to read this; it’s an interesting manifestation of Vesta, though it’s fair to add “at home by the fire” to the mix.

Then, stretching from 3+ Aries to 3+ Libra is an opposition of Mars and Eris. The opposition is exact to one arc minute, meaning 1/60th of a degree. This is so close that it’s impossible to plan. Mars and Eris are acting as one entity, focusing the Aries Point with the precision of a laser. This is in turn amplified by contact with the ascendant, and the other Aries Point planets, including Welles’s Mercury-Pluto conjunction. If you’re getting lost, just follow the numbers — things with similar numbers are in aspect to one another. Chiron and Saturn are brought in by a ‘proximity effect’ of being close to Aries Point planets.

In many previous articles, I’ve described the current Uranus-Eris conjunction as being associated with broadcast media and with the internet. You may recall that in 1927 and 1928 Uranus and Eris were conjunct on the Aries Point, coinciding with the advent of commercial radio, the patenting of the transistor and the early experiments with television.

The Mars-Eris opposition in this chart affirms that Eris is the patron saint of mass media — and its resulting tendency to chaos. Mars-Eris says turmoil like nothing else. Both are deities associated with combat and conflict; Mars is overt, and Eris is covert. Mars describes the “war” piece, and Eris describes the subversive effect that the show was about to have.

Just to add a little extra Aries Point, there was about to be a lunar eclipse right in mid-Scorpio. That alone would spark up the Aries Point effect. And opposite that eclipse was Uranus in mid-Taurus. This chart looks like some astrologer designed it, but it’s just not possible to do that. (And, notably, Eris was not discovered, Chiron was not discovered and I would be surprised if 10 astrologers on the planet were using Pluto in 1938).

In other words, the only way to get this chart is synchronicity. Indeed this whole setup is the perfect definition of synchronicity: ridiculously meaningful, highly unlikely random coincidence. Of course, you don’t see this unless you’re paying attention. Like all beauty, it’s in the eye of the beholder. There would be no astrology, but for astrologers.

A Realtime Media Psychology Experiment

It’s well known that the reaction to War of the Worlds was overblown by the newspapers, partly in their need to discredit the relatively new institution of radio. More likely, it would seem that the newspapers were envious of the instantaneous mobilizing and persuasive power of radio, something that they would never have.

I ran this past philosopher and media theorist Eric McLuhan, son and collaborator with Marshall McLuhan. “Don’t confuse mass audience with large audience,” he said. “A mass audience is a function of speed, not numbers. It can be an audience of two million, or two thousand, or two hundred, or twenty. The distinguishing requirement is simultaneity.”

The impact of War of the Worlds involved that simultaneity. That’s what made it so real to people. Radio beats the tribal drum. Everyone listening hears the same thing at the same time. People gathered around the thing, enhancing the tribal experience. This was then picked up and embellished by the newspapers, which dragged the story out for many weeks, weaving it into a legend that became history.

Anyone in any position of power, or with an agenda of influencing the public, took notice: politicians and other government officials, media companies, entertainers.

Much of the effect of War of the Worlds drew on the power contained in the background: people’s pre-existing fears of invasion and of ‘the other’; the impact of repeated news interruptions (including the most famous one, the Hindenburg disaster about 18 months earlier); and psychic disorientation due to the presence of a new communication medium.

One thing to remember about new technology is that it’s destabilizing. Society rearranges itself around developments like radio, and often this becomes obvious through events like War of the Worlds. But the changes in consciousness and the structure of society happened long before — it was electricity itself that made radio possible, and the earlier development of the telegraph that made communication instantaneous, collapsing space and time. Talk about disorienting.

“Our actual broadcasting time, from the first mention of the meteorites to the fall of New York City, was less than forty minutes,” wrote John Houseman, an actor and producer who collaborated with Welles. “During that time, men travelled long distances, large bodies of troops were mobilized, cabinet meetings were held, savage battles fought on land and in the air. And millions of people accepted it — emotionally if not logically.”

In a 2011 article called “Media Effects in Context,” published in Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, Brian O’Neill made this comment (I’ve removed internal citations for ease of reading):

“While the scale of the panic is known to have been exaggerated, Cantril [the author of a 1940 book analyzing War of the Worlds] was interested in exploring the variability of listeners’ experiences, factors that may have inhibited critical ability for some, and the contradictory accounts, pointing towards how the same information heard by individual listeners was processed in very different ways. Cantril’s claim was that neither educational level, nor the circumstances in which the broadcast was heard, were sufficient to explain the susceptibility to suggestion or the different ‘standards of judgment’ displayed by individuals. Rather, he argued that a combination of psychological personality traits — self-confidence, fatalism, or deep religious belief — predisposed individuals to uncritically believe what they were hearing.”

We may think we’re more sophisticated today, but so are the media magicians. When something like a 9/11 happens, who exactly looks at it and questions whether it’s real? (I’ve covered that particular question in this article from 2002).

w/love,