Link to original (my favorite old-style page)

Dear Friend and Reader:

For the past couple of years, I’ve occasionally posted to my Facebook page the question, “What if the Moon landing really happened?” I can’t take credit for that line — the phrasing originates with Andrew McLuhan, grandson and student of Marshall, who also had a knack for turning things sideways so you could see them better. We’ve been bouncing around the topic for a while.

My question was intended mostly as a thought experiment. I was interested in two things: one, the basis of people’s belief that the Moon landing occurred or did not occur, and two, philosophical ideas about the implications of humans visiting another world for the first time in known history. What if?

The first relates to epistemology: how we know what we think we know. This is a topic that deserves more attention: a whole university department everywhere including the mall. The second was an inquiry to my readers for some ideas about such a profound event: humans actually leaving the only planet we know, and its atmosphere and its gravity field, and landing somewhere else.

At the time, it was a sensational event beyond anything we can comprehend today. Most people were exuberant (and a good few were angry — it was the Sixties after all). The world and society were in rough shape.

Many have, though, commented that by Apollo 13, the third planned lunar landing less than 10 months later, the public was already bored with the whole thing. Ratings were saved by a shipboard disaster threatening the lives of the crew. Their near-death experience, broadcast around the clock, revived interest in Apollo and demonstrated, again, that space travel had risks.

Many people read my “what if” question in reverse, as if I was specifically insinuating that Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong didn’t roam around the Moon on July 20 and 21, 1969.

This was sometimes taken as an insult and affront to their bravery and achievement, and the work of so many people we are told was required to get them there. While I was open about my technical questions (which I’ll come to in a moment), I avoided seeming accusatory. More like acurioustic.

What I found interesting was the extent to which the question itself was regarded as an indictment. It seemed that for many, merely asking was construed as being in denial, or a little tetched, as they say in Maine.

Few recognized that I was asking an actual philosophical question, with a hint of satire. The responses mostly sorted into two camps: the Moon landing absolutely, unquestionably happened (and you’re a nutso conspiracy theorist if you think it didn’t); or, no way, no how: it did not happen, and you’re not paying attention if you think it did; the very notion is laughable.

Were you aware of this seeming divide, till now?

There is also the position taken by Richard Hoagland and others that astronauts reached the Moon and found UFOs and/or glass pyramids and/or other evidence of prior and/or current civilizations.

That theory includes a proposed explanation as to why we did not establish a Moon base there, nor still occupy the territory: the natives were hostile.

Good stuff, right? Will we ever know?

There were a scant few people commenting who gave what I would consider an honest answer: I wasn’t there, so I can’t tell you. Others have admitted something along the lines of, “I think I know, because that’s what I was told.” That’s honest too. One of our staff editors, who seems to support the idea that the Moon landing happened, recently suggested that I am on a quest for the truth.

I told her no, I am just looking for a good question.

The Grand Metaphor

On one level, the Moon landing is a metaphor for our relationship to technology: how amazing it is, how we’re supposed to take it all on faith, including the truth that new scientific developments are good for us, and that scientists are inherently truthful, objective and trustworthy. Do you have any idea how your phone or computer works? Here’s a pop quiz: give me a one-minute lecture on ports. Not plugs, but rather a basic architectural feature of how software interacts with an operating system.

I once explained to one of the world’s top astronomers, whom I adore and with whom I am privileged to correspond regularly, that I come from a field of journalism (environmental toxins) where scientists routinely make up studies, falsify data and cover for one another’s crimes, all because so much money and liability are at stake. Astronomers, we reckon, do not do that.

Over the past year, I’ve done my best to engage a discussion of the Moon landing with some of the scientists I know. I have learned something about where what is supposed to be science meets the realm of belief. In these discussions, men and women of science seemed to morph into protectors of the faith.

One preeminent astronomer I spoke with (someone in what I consider the most exalted class, those who have actually discovered planets) said he had a hobby of engaging the discussion with people in places like airports, and probing why they lacked faith in science sufficient to sustain their doubts. At least he had a philosophical approach and some sense of humor — the kind of scientist who might write a science fiction novel. But his approach was still, ‘so why don’t you believe it?’

I tried to pursue a theory that Moon rocks would be proof positive that people went to the Moon — a physical artifact of some kind. I learned that the Earth and the Moon are about the same age, and that the main difference between terrestrial rocks and those brought home by Apollo astronauts is that there is no geological activity on the Moon: no tectonic movement to speak of, no glaciers, no atmosphere weathering or shaping them.

Moon rocks are “brand new,” in the words of a UCLA geologist who has studied them — they are untouched by forces of nature as we know them on Earth. By that he meant water, ice and air.

In that conversation, I learned that Moon dust smells like gunpowder, and that the dust is a remnant of countless meteorite impacts over billions of years. Imagine all those explosions through the millennia and the ages in the otherwise utter silence of space.

I could not get an answer regarding how someone could prove they are from the Moon.

My geologist source did not say this, which I found in an article: “The rocks of the lunar crust have been repeatedly broken apart by some impacts and glued back together by other impacts. As a consequence, most rocks from the lunar highlands are breccias (brech’-chee-uz), a word for a rock composed of fragments of older rocks. Breccias occur on Earth, but they are much less common than on the Moon.” There are whole bunch of clues there. And apparently the chemical composition of breccias is different on Earth than on the Moon.

The same article, by Randy Korotev at Washington University, continues, “Because breccia refers to texture and anorthositic or feldspathic refers to mineralogy, rocks from the lunar highlands are variously called anorthositic breccias, feldspathic breccias, or highlands breccias. Because the lunar crust has been battered so intensely, there were very few hand-sized rocks collected on the Apollo missions that are unbrecciated remnants of the early igneous crust of the Moon.”

So there was another layer of information. Not all Moon rocks are fresh and young looking due to the lack of an atmosphere or water. Some of those are left, though many or most were smashed together bits of the lunar crust baked into new forms by the pressure and heat of the impact. My prior source was clear that Moon rocks are “brand new rocks,” whereas breccias (which he did not mention) are made of old rocks. There’s a lack of old original igneous (volcanic) rocks laying around the lunar surface because most have been smashed and re-formed by impact events.

First Impressions Mean a Lot

I was born in March 1964, so I was a little kid becoming a big kid during the years of the Apollo mission. I have a distinct memory of seeing the 1969 event broadcast live, as a five-year-old. It was dark. Little B&W TV in the living room, something very special, up at night, parents focused in a way I had never seen.

I was so into the whole Apollo mission thing that I told my nursery school teacher (in front of the whole class) I would be going to Cape Kennedy to see the launch, and she believed me. This was one early initiation into how dangerous lying was.

My early association with the word “NASA” is down-home American goodness. At the time, the government had a horrid reputation. This was in the peak era of the Vietnam War, with a lot of dead American kids involved, and turmoil in the streets, though somehow NASA was considered impeccable: pure scientists who could do the impossible. Really, they were one of the historical bright spots in the midst of it all, though this was fantastic image polish for Uncle Sam.

Even though I now know NASA was and is largely a military program (the crew of one Space Shuttle flight consisted of seven colonels! What could they possibly be doing?), I still can’t shake that friendly impression of them.

Many people associate NASA with a kind of technological perfectionism, though this has been obviated by the Apollo 1 fire that killed three astronauts, and the Challenger and Columbia disasters involving the Space Shuttle. (I have not been able to figure out why all three NASA disasters where astronaut lives were lost occurred on dates within a window between Jan. 27 and Feb. 1, with the Sun in mid-Aquarius; many astrologers have tried to figure this out.)

The Understated Eagle Scout Armstrong — and Laika

That all said, I love the Moon landing story as it is remembered in myth and song. It’s perfect. Half a million people working together, for a supposedly peaceful goal of humans landing on a body other than Earth for the first time. I love the incredible ingenuity of how the Apollo flights progressed, each with its own special mission, each building on the prior one, and preparing for the next.

Who doesn’t love the unassuming, understated Eagle Scout Neil Armstrong? He had been a civilian test pilot, still recovering from the loss of a child, when he landed the lunar module on the Sea of Tranquility with less than 30 seconds of fuel remaining.

(By his instruments’ estimation, it was 20 seconds; he said that subsequent analysis on the ground determined 40 to 45 seconds).

Then there was John F. Kennedy, who in the late 1960s had the beatified status of a saint. Just four months into his presidency, Pres. Kennedy had said to Congress in his brash and elegant way, “I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

The next year, in 1962, he said at Rice University in Texas:

“We choose to go to the Moon. We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills; because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win.”

We could use some of that spirit today, in our time of No Can Do.

It’s not just that the past has been swallowed by digital and deleted. Today we can barely imagine how intense the “space race” was, and how closely it was related to both the nuclear arms race and the Cold War. (Please, see the film The Atomic Cafe.)

Short of nuclear annihilation, there could be no winning the arms race or the Cold War — so the space race became the proxy. And that, really, was not such a bad thing, compared to the alternative. The astronaut thing went on all through the late 1950s, emerging in consciousness as a permanent feature, with the Russians successfully launching the Sputnik satellite. Then it was 2-0 for Russia when Yuri Gagarin orbited Earth and splashed down safely. Americans were panicking. The Russians were tied in the Arms Race, and winning the Space Race.

The USSR sacrificed the canine Laika, the first animal in space, deciding that re-entry with her alive was unnecessary. She had been picked up as a stray, and turned out to be intelligent and the sweetest of creatures. She proved that, for a while, survival in orbit was possible.

Finally our team got John Glenn up there for a few orbits, and we were back in the game.

As They Tell Us

Then, per the official story, in a concerted, sometimes misguided, sometimes frantic effort (and sometimes disastrous, and always heroic, and often brilliant), the United States is said to have developed the technology over the course of about seven years to leave the Earth and inhabit another planet, if only briefly.

Get this: the first flight of the Saturn V rocket, that is, the Moon vehicle, was in November 1968, for Apollo 4, just nine months before Apollo 11 flew.

Getting people onto the surface of the Moon is variously described as the greatest achievement of humanity, or of science, or of the Americans, or all of the above. Maybe something even bigger. Here’s some typical language, from a PBS description of its Race to the Moon special series:

“In the early morning hours of December 21, 1968, three astronauts strapped themselves into a tiny capsule perched atop the most powerful rocket ever built. They were about to attempt the most daring, dangerous mission in the history of exploration: a journey from the earth to the moon. If they succeeded, they would realize a dream that had captured people’s imaginations since time began. If they failed, the United States would be forced to cede technological dominance to the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War. The three men were the crew of Apollo 8 — the first manned mission to the moon.”

[Note, Planet Waves style capitalizes Earth and Moon; PBS style does not; most style guides don’t, which I’ve always found puzzling. Earth is not a proper noun?]Could any or all of that somehow not be true? Embedded here is the concept that if you don’t accept the fact that we actually went, you think America is a total loser, or worse, a phony. It is this kind of stacked thinking that makes me wonder who has actually thought this through. It’s a question where independent thought verges on prohibited.

The Moon landing, in American lore, is like the Resurrection to Christianity. It is supposedly proof that we are divine beings, who were able to ascend to another dimension. It is presumably proof that we are the greatest civilization on Earth, and have the greatest scientists on Earth.

While I have my questions about the imagery, and how the cameras functioned, and how battery-powered air conditioners were able to make the 260-degree temperatures survivable, the source of my doubt involves how even asking whether and how this great feat happened is akin to blasphemy.

Seven Little Questions

Here are the questions that I have not been able to get answered, and which are currently open accounts. They all should easily sail through fact checking if men indeed walked about on the Moon. I am interested in seeing verified, data-based responses to these queries — not speculation. Here goes:

1. The heat issue. The surface of the Moon is 260 degrees F. during the day (day lasts two weeks), 48 degrees hotter than boiling water. I don’t understand: A. how you can really insulate for that (the claim is Mylar), and B. how a battery-powered air conditioner could have enough juice to lower the interior temperature to 80 degrees (a sustained interior/exterior differential of 180 degrees) inside the lunar module (or LM, pronounced lem). I would also like to see verified data on the testing of the space suits, proving they could withstand that kind of sustained heat, essentially an oven, for hours.

2. No blast crater; no dust on lunar module feet. Neil Armstrong specifically notes at the beginning of the first moonwalk that the lunar module did not leave a blast crater when it descended with considerable downward vertical thrust. I want to know why not a grain of Moon dust is visible on the feet of the lunar module in any photo. The downward thrust would have churned up a lot of that dust in a 1/6 gravity environment, it would have gone everywhere, and settled in place.

3. How did photographic film survive at such an extreme temperatures? Even if it didn’t shrivel up like lasagne, pre-digital photographers well know that a little heat harms the emulsion of color film and you don’t get clear pictures. There are many other problems with the photographic records, some of which are described as common of attempts of photographers to simulate the powerful single-source effect of sunlight, making all the usual mistakes. But that doesn’t matter if your ordinary Kodak film has melted.

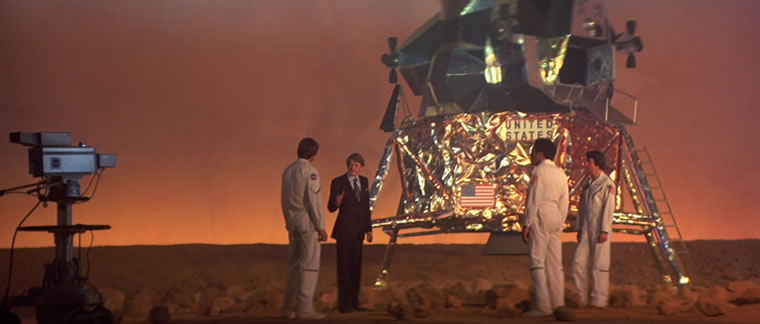

4. How does the video camera pan the shot of the LM ascent stage taking off from the Moon? In other words, the video frame follows the small craft that took the astronauts from the Moon base to the Command and Service Module (CSM), even though there is nobody else left on the Moon. Unless it was one of the hostile natives doing them a favor. To use a colloquial expression, it looks fake. NASA used a lot of simulations to create video images, though usually they would say “simulation” on the screen, with the little toy doll rocket ship twitching. I remember this from watching as a child and asking my parents about it. Aside, over the years, I’ve seen credible discussion of a whole lot more imagery issues than these. It’s not just the few obvious ones you see debunked (the most common being the “no stars in the sky” issue). Most are much better than that.

5. How is it even meekly possible that all the original video footage of the Apollo 11 Moon visit was lost? By that, I mean the 10-frames-per-second signal that was re-broadcast in that jumpy, ghostly image on global television. Yes, it was lost. In the National Archives. Or it was erased to record something else — and never found. I mean it. Fact check me. The best we have is restored second generation footage. There’s a recent episode about this on the Science Channel.

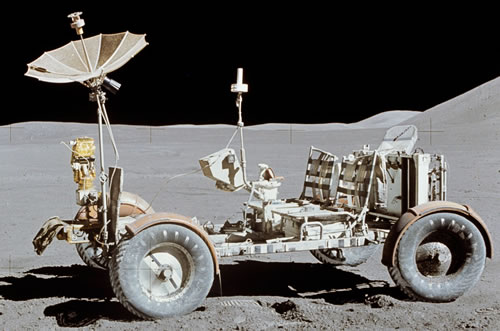

6. Issues With Dish TV: Italian filmmaker Massimo Mazzucco makes an interesting point when he says that on one of the later missions, a transmission dish is mounted on the lunar rover, that little jeep they used a few times. So is a camera, and you can see the landscape bouncing around as they go over bumps, sometimes shaking the frame as much as 15 degrees. How, he asks, does the satellite dish, which requires to-the-degree alignment to connect with the receiver, manage to keep broadcasting while they’re out four-wheel driving?

7. The Moon rock thing. I want a competent, concise and non-defensive explanation of why what we think of as Moon rocks can only come from the Moon. That should be easy. If this article is true, and it seems well researched and well presented by someone with a clue, it supports my theory that Moon rocks would be absolute proof — assuming, of course, that we have chain of custody documents establishing their source. As with any environmental sample, that documentation should exist, and we need to see it.

I want to hear the rest of my issues explained like you would explain something to a child: honest answers to questions one through six. As our old friend Carl Sagan said, extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof. If that applies to ESP and astrology (which is what he was talking about), let’s apply it to science. Of course, most people think of the Moon landing as ordinary and requiring no proof at all.

Is that too much to ask? Just seven questions? After 50 years, the answers should be easy to find and easy to understand.

I won’t get into the Van Allen radiation belts that surround the Earth, which are variously claimed to be deadly or harmless. Whichever it is, they seem to act as a preservative. Many of those early spacefaring astronauts who we are told crossed through them have lived into their 80s and 90s. This controversy exists, though I’ve set it aside for now.

I am open to the possibility that the Moon landing happened, but that the film and video were “simulations,” as NASA called some of its imagery. Maybe they were hiding the space alien base that would have been in the shot. Maybe they didn’t want the USSR getting any real images of our gear. Maybe they never solved the film issue.

I’m not one of those people who just believes things. As your personal journalist, I am certain that’s a selling point. However, to maintain this position, I experience more than my share of being called a fool for asking what I think are sincere questions that any little kid would want to know. This gets me into trouble occasionally, though I keep doing it.

So, no, I don’t merely believe the Moon landing happened. I also don’t believe it didn’t happen. Believe is what you do when you’re unwilling to endure a lack of data. I’m willing to do that uncomfortable thing and stand in the face of the unknown. Even stranger is the peculiar way in which “it did happen” and “it didn’t happen” exist in seemingly parallel realities in my mind. Have you ever heard of morphogenetic fields? There seem to be at least two surrounding the Apollo mission. I keep encountering the parallel reality. It seems equally true and untrue.

Two Other Questions: Why and How?

Before I get to the essence of my What If question, there are two points that deserve reflection. One is: why might NASA fake the Moon landing? The other is, how could they possibly do so? I will address both briefly, to the best of my ability, after pondering this all for a decade or so.

The Space Race was a proxy for the Arms Race, which was a proxy for World Domination, and we simply Had To Win. There was no way those “damned Ruskies” were going to get the best of us, and be known and remembered eternally for this great technological achievement.

My theory under one scenario is that NASA sincerely tried to do it; that they wanted to; and that they built a legitimate program, at first, and got close — and then for whatever reason, they figured out it would either be impossible, or too risky. They could not leave dead astronauts on the Moon. That would be worse than not going at all. So under this scenario, the solution became, “Let’s not, and say we did.”

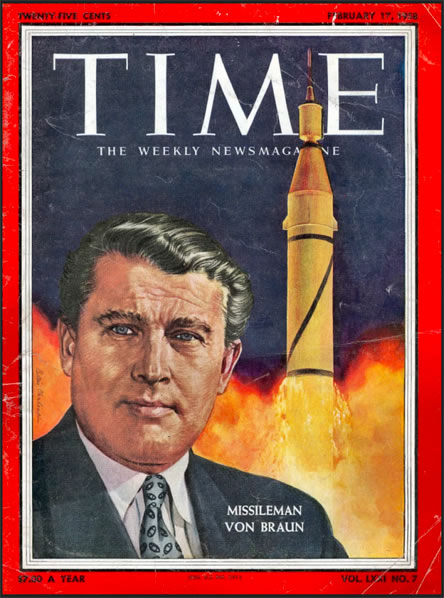

There is another more sinister theory, which is how all that rocket science and money went into rigging the planet with nuclear bombs. The eminently charming, handsome genius behind the Moon landing, Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun was a devoted servant of Der Fuhrer before he became the rocket science genius behind both the space program and the nuclear missile program. And today, we worry about skinheads on Reddit.

Von Braun was imported to the United States along with a thousand rocket scientist “refugees” from Germany right after World War II as part of something called Project Paperclip. There was a special military operation devoted just to his personal delivery.

These Nazi scientists were spared trials and hanging at Nuremberg, so they could help us conquer our mutual enemy, the USSR. Who had sided with us against the Nazis just a few years earlier. It was almost like that scene from 1984 where a TV news reader is handed a new script live on the air, and the enemy changes on the spot. And the announcer says, “We have always been at war with the Soviets. The Germans have always been our friends.”

Maximilian and his thousand physicists were behind the nuclear missile program (intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs) and the space program: both were led by Von Braun. He had been the equivalent of a major in the SS (one rank below colonel). And then he was, personally, the chief architect of the Saturn Vsuper heavy-lift launch vehicle that the Apollo program was based on — that great icon of American achievement and status.

I know, my head is spinning too. You’ll think of this every time you see a paperclip.

Classification and Compartmentalization

Remember — the SS was the agency that ran the concentration camps and were responsible for most of the Nazi atrocities. In the ’50s and ’60s, von Braun’s Nazi past would graze the surface of scandal, though it never quite stuck. He was another one of those Germans who had no clue what was going on down the street. That’s what he said when he was cornered. Oh, I was here, and that was there — just like the people living a mile from Auschwitz.

Rather, he was widely regarded as the very hero of the space program, without whom it would not have been possible. So summing things up, in the 1940s he was involved in the relocation, arrest, gassing, shooting, starving and strangling of 12 million people, and in 1958 was hailed on the cover of TIME magazine. This gives you an idea how impeccable NASA’s public relations machine is.

The second issue The second issue involves how faking something as vastly complex as the Moon landing might have been possible. Let’s put it this way: stranger things have happened.

The Apollo program was classified; it was part of the Cold War and inolved the very pinnacle of American technology (which eventually found its way into every facet of life).

Classified programs are also compartmentalized on a “need to know” basis. People involved have little or no notion what is happening outside their particular classification or compartment. This is understood by people in this line of work. So in the end, very few people would have any basis for knowing what did or did not happen. Many government programs work this way.

Two historical events that come to mind are the development of the atomic bomb and the infiltration of every major media outlet in the United States by the CIA. I understand, or pretend to, how complex an operation concealing any shade of non-Moon landing (even far short of a hoax) would have to be. I also have some sense of how complex the two historical examples I gave are.

And one other thing: people holding classification take it seriously. They tend not to talk, whether from a sense of duty or for not wanting to end up at the bottom of a lake. And if anyone with high enough clearance did go to the press, public incredulity would take care of any possibility of being taken seriously, like those 9/11 truth fruitcakes. The news is run by gatekeepers, who define what is and is not in the realm of the acceptable.

There are many massive programs that operate under the cloak of secrecy and compartmentalization. We are surrounded by them. And on the other side of awareness, what we can actually see, there is a strenuous effort made to shape the public dialog by deciding what is acceptable and what is not.

The Moon landing is the very least of it. We might be asking ourselves: what if all those ICBMs actually happened?

What if the Moon Landing Really Happened?

Recently PBS re-ran its Chasing the Moon series referenced above. In one episode, there was an extended interview with Apollo 8 commander Frank Borman.

The way the schedule worked out, Apollo 8, the first flight to orbit the Moon, was up there on Christmas Eve. Knowing they would have the largest audience in TV or radio history, someone suggested that they bring a Bible and recite the creation story from Book of Genesis.

I wish I had Frank’s exact words; I can only paraphrase. He said that while reading the story, he realized that all religion is set up with the Earth at the center of everything and as the most important place in the universe and the only thing God cares about.

From Frank Borman’s point of view, this was ridiculous because he could see with his own eyes that the Earth was just a small part of everything. While their reading from the Bible felt sincere to me, and does to this day, his view from the window undermined the whole notion of worldly religion right on the spot. I’m also a fan of the Apollo 11 press conference, which is worth studying. At their first meeting with the press since returning home from the heavens, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins were asked to comment on their achievement from a spiritual or philosophical perspective: what is the real meaning of this thing you’ve done?

On that day, Buzz Aldrin said, and again I paraphrase, that it shows what we can do when we work together. What other problems can we solve, now that we know we can do something this incredible?

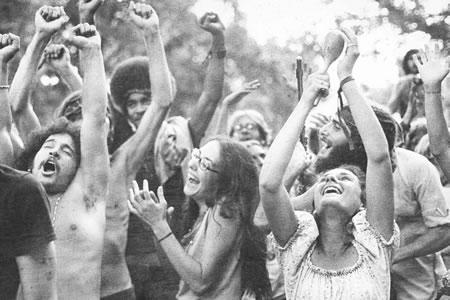

One might think this would lead to a kind of revolution of spirit. And in their era, it seemed they were part of one. The 1960s, for all their problems, were a time of greater participation and involvement. Despite the chaotic state of society, just weeks later, 400,000 young people gathered on a field in Bethel, Town of White Lake, for the Woodstock Music and Arts festival. Though it was not intended as an anti-war protest, it certainly became a declaration of the desire for world peace, complete with its own proof.

That “Earthrise” photo from Apollo 8 became an icon of the nascent ecology movement, which was spawned a decade earlier with the publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. This was the first popular work to explain what an ecosystem is. (DDT spraying did not kill birds directly. Rather, the spray landed on the leaves, which fell to the forest floor in autumn, were eaten by worms and concentrated in them, the worms were then eaten by birds and killed; hence springtime, usually filled with birdsong, went silent.)

Combine that with Earthrise and maybe we would see that humans were poisoning our one and only planet — and would stop. But we humans, aided by made-of-human corporations, did not stop; the spraying got worse, the chemical pollution got worse, and the nuclear incidents started to happen. After 141 above-ground atomic blasts [verify against American Ground Zero], the meltdowns happened one after the next and the spent nuclear fuel has piled up to the point where nobody has a clue what to do with it. Finally, the notion of putting it in a salt mine seems disgusting and futile.

Though the Earth has only 2.5% fresh water (the rest is salt water), we somehow allow fracking to destroy drinking and irrigation wells all across the landscape, from sea to shining sea and on every continent besides. We’re happy to turn on the stove and have some of that gas come out. And then there is global warming. In one gesture, industry destroys our drinking water supplies, and puts carbon into the atmosphere.

False Messages of the Moon Landing

Maybe we cannot count on the revelations of those astronauts taking hold: that the Earth is not the center of it all, and that we have to work together (without being paid by the government or Grumman Aircraft to do so). Or maybe you had to have the experience directly — maybe you personally had to be looking out the window of the Apollo 8 command module to see through the ruse of religion, and embrace the concept of massive cooperation toward a single goal.

However, in the case of the Apollo program, that single goal everyone worked toward was corporate: funded in the billions by taxpayers only with indirect consent.

World dominance was the goal, whether psychological (we’re the greatest) or military (winning the Cold War). That is not pure science; it’s not knowledge for the sake of knowledge.

NASA, the master of public relations, managed to help its government put a friendly face on global destruction, dressing up the ICBM as the friendly Saturn V.

And they did so under the leadership of a high-level Nazi as their chief architect.

The Moon mission is over, though the world is still rigged for nuclear annihilation. Young people still sit next to ICBMs on aircraft carriers, in submarines and in underground silos in Kansas. Do we count all those missiles as the crown of technological achievement?

Humans, as a lot, are notoriously terrible at learning from our experiences. Only occasionally do we do the right thing after trying every possible wrong one. Our potentially nimble, creative and ingenious minds are usually as dense and cobbled together as Moon rocks — often consumed with jealousy when we’re not obsessed with personal survival rather than collective.

As has been said a few times, the human mind/spirit is capable of brilliance and transcendence, and astonishing pettiness and short-sightedness.

One of the most revealing types of image from the early space program showed how thin the atmosphere is — how fragile, meaning, how fragile we are. Are we getting the message?

Ultimately, the message of the Moon landing, whether real or simulated, is that we can leave the Earth. That is what was demonstrated, and what we were told and largely accept was real. Whatever message of ecology or about how the Earth is not the center of the universe may have been conveyed philosophically, the thing done was leaving.

And that’s not a valid message, if we are thinking in terms of growth and progress. In fact, we humans are stuck with whatever we do to our planet. There is nowhere to go but here.

With love,