Can we consider that the digital world in general has now reached the point (perhaps long past the point) where it serves the oppressors far more than it serves us?

By David Perez

Two dangerous things are happening simultaneously.

First, the official COVID narratives are mutating in ways that threaten to make it a forever phenomenon—unsurprisingly to anyone who’s been paying attention. Second, the titans of Hi-Tech, in league with the Deep State and its political lapdogs—are hell-bent on eliminating voices of dissent on various Internet platforms.

It seems to me that we have to fight extreme with extreme. But our extreme might be simple. Hard, yes, but a very direct action. Might we, for instance, begin our resistance by ditching our smartphones? In the one’s and two’s? Or in rallies where we dump them en masse? Might this make the agenda of the corporate and political elite harder to implement, particularly all the surveillance apps supposedly for our health?

While we’re at it, can we consider that the digital world in general has now reached the point (perhaps long past the point) where it serves the oppressors far more than it serves us? Has our habit of evaluating the benefits of technology in strictly personal terms been trumped by its use by empire for economic, political, social and militarized rule?

Can we overcome the feeling that high tech is a runaway juggernaut we’re helpless to control? Re-imagine an old normal independent of behemoths like Facebook, Google, Amazon and Twitter, free from the tyranny of algorithms, our self-worth measured in digital likes and shares?

When does acceptance become surrender?

It seems to me that we have to fight extreme with extreme. But our extreme might be simple.

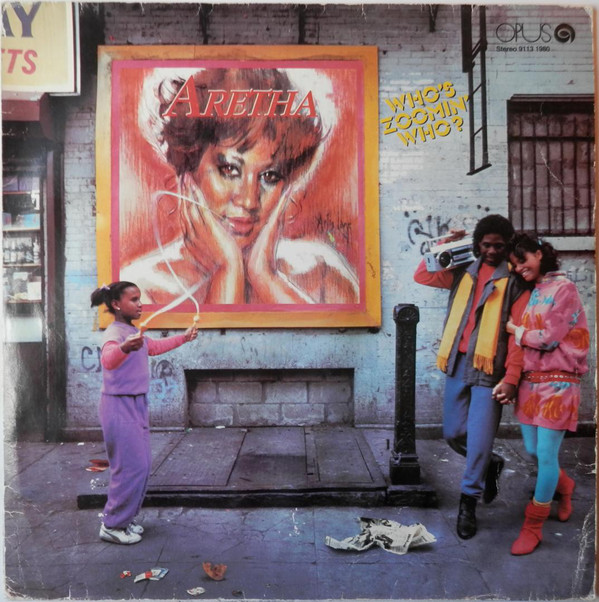

Who’s Zoomin’ Who

I realize, of course, that because of COVID, millions of people are now more dependent on the Internet and apps like Zoom for their bread-and-butter, and only for the grace does my income situation enable me to opt-out. Nevertheless, it’s a real question: Is our being forced to spend more time online potentially another health hazard? To quote that 1985 Aretha Franklin song: “Who’s Zoomin’ Who?”

It could very well be that the Luddite Might-Wannabe inside me has fed over the years by my job at Op Cit Bookshop in Taos, New Mexico. Formerly known as Moby Dickens, the store has been operating in the same location for over 30 years as a time machine to the past, some might say an ancient past.

Our Point of Sales (POS) system still runs on MS-Dos, the precursor to Windows built-in 1977 and too old to be linked to the Internet. The computer monitor is a CRT with green lettering and the keyboard functions with F keys. We also use an Okidata Dot Matrix Printer. The only thing missing is Pong.

What makes one tool superior to another has nothing to do with how new it is. What matters is how it enlarges or diminishes us, how it shapes our experiences with nature and culture and one another. — Nicholas Carr

The Sentimental Fallacy and Long Lasting Low-Tech

Alas, we do have a laptop with a Wi-Fi connection, which allows us to order inventory from distributors like Ingram, as well as checking emails and doing research on bookstore-related news. But by and large Op Cit operates very old school. We even use index cards and scrap paper to take special orders and leave each other notes.

When customers, a steady mix of locals and tourists, discover how low-tech we are, they invariably respond with something like, “Oh my God, that’s so awesome!” Many of them, youth in particular, wonder how such an old operating system could have lasted this long. We wonder the same thing.

Personally, the Op Cit experience has caused me to examine just what it is that I truly need. As science author Nicholas Carr wrote in The Glass Cage: Automation and Us (W.W. Norton 1994): “We assume that anyone who rejects a new tool in favor of an older one is guilty of nostalgia, of making choices sentimentally rather than rationally. But the real sentimental fallacy is the assumption that the new thing is always better. What makes one tool superior to another has nothing to do with how new it is. What matters is how it enlarges or diminishes us, how it shapes our experiences with nature and culture and one another.”

I can’t shake the feeling that perhaps we’ve reached a crossroad, maybe gone past it. That digital addiction has become the real lockdown, hiding in plain sight, weaponized on behalf of the ruling class.

Less Enamored with Digital

Writer and reporter David Sax makes a similar point in The Revenge of Analog (Public Affairs 2016), a detailed book that shows how youth are at the forefront of getting unplugged from a relentlessly digitized world. Sax writes: “There’s an argument that the world has fundamentally changed and we should just get used to it. That the amount of time spent on computers, smartphones and so forth is because the young love it, it’s their way of communication. To deny that is to deny reality. Moreover, the technology is good; it is liberating and has opened vast new frontiers.”

The book shows how it’s the exact opposite. It is the younger generation that has become less enamored with digital technology, and warier of its effects. Sax explains: “These were the teenagers and twentysomethings out buying turntables, film cameras, and novels in paperback. They were the students who told me how they would rather be constrained by the borders of a page than the limits of word processors.”

Good to know, right?

Hey, I totally get the challenges. The Internet is a vast resource with enormous benefits. This very article for this very website demonstrates its use value, and I’ve been clicking and scrolling for decades. Still, I can’t shake the feeling that perhaps we’ve reached a crossroad, maybe gone past it. That digital addiction has become the real lockdown, hiding in plain sight, weaponized on behalf of the ruling class. And as I stated in the beginning, their agenda relies heavily on pumping up the drug.

So, might our ultimate liberation depend on getting unplugged, or at least moving in that direction? Extreme measures that lead us back to community and love?

David Perez is a writer, journalist, activist, and actor living in Taos, New Mexico

Let’s whisper this story in one another’s ears in the old game of Telephone, and see how far it travels, so softly and intimately.

Yes! Yes!

I love the image of a pile of discarded smartphones, ready for rare metals reclamation, surrounded by people holding hands and singing. A bit Suesian- Whos down in Whooville Center- but maybe more attractive for all that color and curvy weirdness. Can’t get more analog than that. Sign me up on one of your index cards.