New! Press Room — International Coverage of Eric Francis

Note, this edition is up to date as of Dec. 25, 2019. For a newer edition, see “About”

“I look out across the slumbering sea of humanity and I whisper these words in the night. And I know that I address a great being sleeping still in ignorance of itself. I know that if the wild winter winds of your communication systems send tatters or fragments of this message echoing in the darkness, it will still be to the unconscious that I speak. For the conscious have seen the sky start to brighten in the east and have felt the warming spring of eternal life begin to thaw the hardness of their preconceptions.”

— The Starseed Transmissions

I AM A horoscope writer — the kind who appears in the backs of magazines and next to the puzzles in the newspaper. That’s one of those unusual jobs where someone would definitely wonder how you got into the work. Many people question whether it’s even real, and hardly anyone has met someone who writes them.

Very few astrologers dedicate their work to this particular form. Many feel that it’s an insult to their profession. I think of it as astrology’s most elegant and practical medium: 100 words in a magazine, no birth time necessary, for free. If that reaches someone, astrology is serving a purpose.

I’ve written horoscopes for daily newspapers around the world, including the Mail and Mirror in London; the Daily News in New York; the Sydney Morning Herald in Australia; and countless magazines, from Marie Claire to Harper’s Bazaar; from Canadian Home to Flaunt.

I am also an investigative reporter — the old-school kind, who takes years to develop a story. My specialty is scientific fraud associated with chemicals so toxic they are measured in parts per trillion, called PCBs. I cover the history of environmental pollution and how it was concealed from the public, the press and the government. I could step before an audience right now and give an hour presentation on the history of Monsanto, without referring to notes.

Sierra, the Village Voice, The Ecologist and the Las Vegas Sun have published my articles, among many other national publications. For years I covered PCBs for Woodstock Times, a body of writing of which I’m the most proud. My document collection fills many good-sized file cabinets, and a storage unit and a massive repository on Document Cloud.

My work as an astrologer has taken me all over the world. This story begins in a little town in New Jersey, and explores a cave in upstate New York. From there it passes through the King’s Chamber in the Great Pyramid at Giza. There are extended visits to London and York in England, then to Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam, Vancouver BC, Miami, and an island off of Tacoma called Vashon.

Though I’ve lived it all, I’m as curious as you are to see what happens, and how it happened. As of this writing, what all these places have in common is my horoscope column, called Planet Waves. Well, it’s a bit more than a horoscope. Though I am known by most people as an astrology columnist, I remain an investigative reporter in two senses of the term. One is that I’m an accredited photojournalist, ready for any assignment that might be appealing.

The other is that my astrology articles about world events are often a fusion of classical journalism and thoughtful astrology. You might say that I conduct cosmic investigations. But I always remember my basic credo: Astrology is better as a tool for asking questions than it is for getting answers.

I Never Planned to Be an Astrologer

Astrology found me. When I sat down at the Warren Township desk of the Echoes-Sentinel newspaper at age 22, my first professional job as a journalist, there was a calendar with planetary glyphs and the lunar phases hanging on the wall next to me.

I would stare at it while I typed articles about municipal development, the rescue squad and town government, wondering what it all meant. Flo Higgins, my editor, was the one who knew. The editor of the Echoes was also a professional astrologer, who owned a New Age bookstore on the Jersey shore in Fair Haven, called Aquarius Rising. This is unusual; typically the closest a newspaper gets to astrology is a syndicated horoscope column.

Her so-far 27-year run as editor had included lecturing and/or predicting turns of fate and fortune to a generation of young journalists — and everyone else within a 25 mile radius, one on one.

(As an astrologer, she was a little old school in her approach. She said she was paid about $40 an hour, an astonishing sum of money to us.)

By working for the Echoes, one had unwittingly subjected oneself to Astrology 101, complete with lectures on Mercury retrograde, your upcoming Saturn return, timing events around the Full Moon, and tarot cards in the office.

This was probably not the place one was trained to work when attending the Columbia School of Journalism.

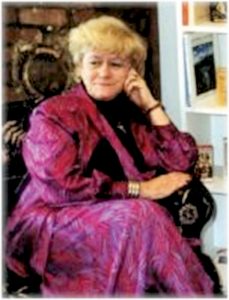

Flo was an unusual blend of properties, principles and aura that one took for granted because it was just her. She could be brusque and chilly and bossy, and utterly arbitrary, but if you gave her some time and space to be herself, you figured out she had a heart of gold and was in possession of some true wisdom. And once she believed in you, her faith was unshakeable.

There was no doubting the power of this force of human dominance. Her comportment blended a cigar chomping news editor, a football coach and the psychic at the end of the amusement park pier. In her purple lamé shawls, her high heels and slightly heavy set frame, she would vibrate the floor as she walked past my desk, invoking the gods.

Or ordering me to call the police department. If you asked her a question, any question at all, there was a 50/50 chance she would growl, “Call the cops!” because they know everything.

So the Warren emergency dispatch desk served as a kind of personal Echoes-Sentinel municipal information concierge for everything from the time of events, to getting help tracking down the mayor, or ascertaining data on whether a certain road was still closed and for how long. (Every police department has a non-emergency number; that’s the one to use for routine business. You don’t dial 9-1-1.)

The Random Page of a Newspaper

How did I find Echoland? I was 22 years old and it was 1986, recently graduated from the State University of New York at Buffalo. At the time, I was living in a place called Miracle Manor. This was a community of about 20 people who had rented an old convent in central New Jersey, where we had devoted ourselves to the study of A Course in Miracles, a kind of do-it-yourself program in spiritual psychology.

I had just gotten fired from my table-waiting job at the Sizzler Steak House, a great development because I wanted to be a writer. But I had no idea how to go about it.

One day I was sitting at the dining room table of Miracle Manor, complaining to my girlfriend Ginger about how there were no jobs for writers. So she said, well, maybe check the classified ads. I thought, oh, how can it be that easy? Ginger is a practical person, and there’s also something unusual about her perceptions. She reached for a single sheet of newsprint lying on the table. The odd thing was that this random page happened to be from the classifieds of the Newark Star-Ledger.

She picked up the page and looked at it.

In fact, it was from the help wanted section.

She looked closer, and it happened to be the ‘W’ page. The Star-Ledger is a really thick newspaper, and there could be 40 pages of tiny classifieds on any given day (that was life before the internet). So I was intrigued when, on this one random page on the dining room table at the particular time of this particular discussion, she found a classified ad for a writer job at a local newspaper just a few towns away. Writer begins with a W. What a coincidence!

Yet at the same time, somehow it seemed normal; this was the kind of thing that happened every day at Miracle Manor. I can’t say that I ever got used to it, but after a while one got the idea that these unusual little occurrences were actually the miracles to which the course was referring; and that miracles were normal.

The ad said something about the job being for an entry-level writer to cover Warren Township. So I picked up the phone and called the Warren Town Hall and got the secretary of the Planning Board on the phone, Mrs. Wimmer.

She knew the job was available; it was a small town. There was a Planning Board meeting that night, and I asked if I could come; of course, it was a public meeting. So, after dinner, I got in my gold 1972 Dodge Dart, drove the 20 minutes down I-78 (a new highway that would soon enough factor into every last article I wrote), and showed up with my notebook.

The meeting pushed the experience of boredom to existential depths. The Planning Board is where new housing developments are discussed, sometimes in excruciating detail. (Actually, the Board of Adjustment was worse; it would fix the problems created by the Planning Board; but fortunately in Warren, there was an Echoes tradition of ignoring the Board of Adjustment, because there were so many other stories. I’ve never been once! I’ll have to get there some time.)

Mrs. Wimmer was kind and supportive, she took the Planning Board seriously (it was truly her life’s work), and she seemed happy to conspire with me to get the job. At the meeting, I met a guy named Andy, the college student on winter break who was filling in for what would be my job. He was sitting at the back of the room covering the meeting, and in a few minutes he needed to go back to write the story. I introduced myself. He, too, seemed willing to enter into a conspiracy for me to get hired.

He explained that the editor was someone named Flo Higgins.

“She’s an astrologer,” Andy said.

“An astrologer?”

Everyone had the same reaction.

“Yeah, she has a bookstore down the shore called Aquarius Rising. It’s her other job. She charges $40 an hour to read charts.” I had no idea what an astrologer was, but it sounded New Age. I was not much of a New Ager, but technically, A Course in Miracles was also New Age, and so were a lot of other things I was doing.

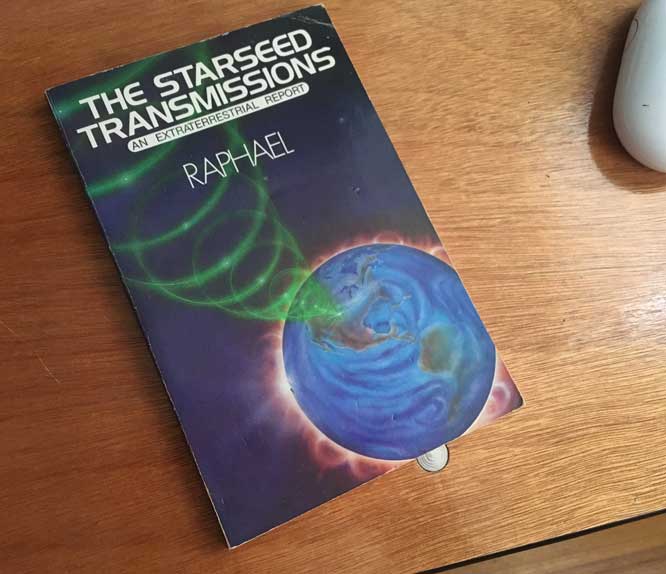

The Starseed Transmissions

I learned from talking to Andy that Flo was right on this wavelength. Right then and there, I devised my plan for The Starseed Transmissions, which at the time was a hit book on the New Age scene, to fall out of my bag during the interview. It was a good thing, too, because Flo thought I was a terrible writer and I probably would not have got the job otherwise.

A few days later I showed up for the interview. The Echoes office was in a ramshackle building on Main Street, with sagging floors and a bathroom piled high with the collected reporter’s notebooks of perhaps a decade or more. Hiding in a little alcove in the back of the office was the great Flo Higgins.

Intense barely begins to describe her. Bleach blonde, 60ish, no-nonsense and reluctantly authoritarian, she was high-strung, judgmental, and pissed off, but no matter how hard she tried, she could not hide her kindness or her genuine Irish-style warmth and generosity.

She had no idea I knew anything about her, that I had talked to the guy who was sitting at what would be my desk a few feet away, or that I had been spying on the Planning Board.

She asked me about my experience and all the usual job interview questions. I told her I had started a magazine in college, called Generation, and had done lots of writing and produced some political campaigns. She was nonplussed, but in an enthusiastic sort of way. It was as though she would go out of her way to show you how unimpressed she was.

Finally, when the moment seemed right, I reached into my bag and out fell The Starseed Transmissions: An Extraterrestrial Report, its friendly green cover shimmering on the floor.

“Oh, The Starseed Transmissions. Why are you reading that?”

She knew the book, just as I had predicted.

“I live in Miracle Manor.” Well, actually, Ginger had read me the book on the phone over the summer, before we got there.

“Miracle Manor? What’s that?”

I explained that it was a community in Piscataway created to study A Course in Miracles.

“Oh really? Well I’m an astrologer,” she said matter of factly. “And I have a bookstore down in Fair Haven called Aquarius Rising, and we sell The Starseed Transmissions and A Course in Miracles.”

“Oh really?”

And so on.

Well, naturally, I got the job — but only after I found out what a horrific writer I was, how I had written the worst test story in the history of the newspaper, and how she was going against her better judgment by letting me do a second test article about the Planning Board, because my first one turned out so terrible, and how in all 27 years of being editor of the Echoes she had never given anyone a second chance to cover a meeting and write a test story.

The two other writers felt the first story wasn’t all that bad, but they knew Flo and were clearly trying to help me get the job. Of course, she was right. I had no idea how to write hard news copy, and my first story totally missed the point. (A meeting can go on for three hours, and the thing that makes headlines takes just 30 seconds.)

I demanded a second chance: any editor knows that a reporter has to be persistent, so I figured it couldn’t hurt. She relented.

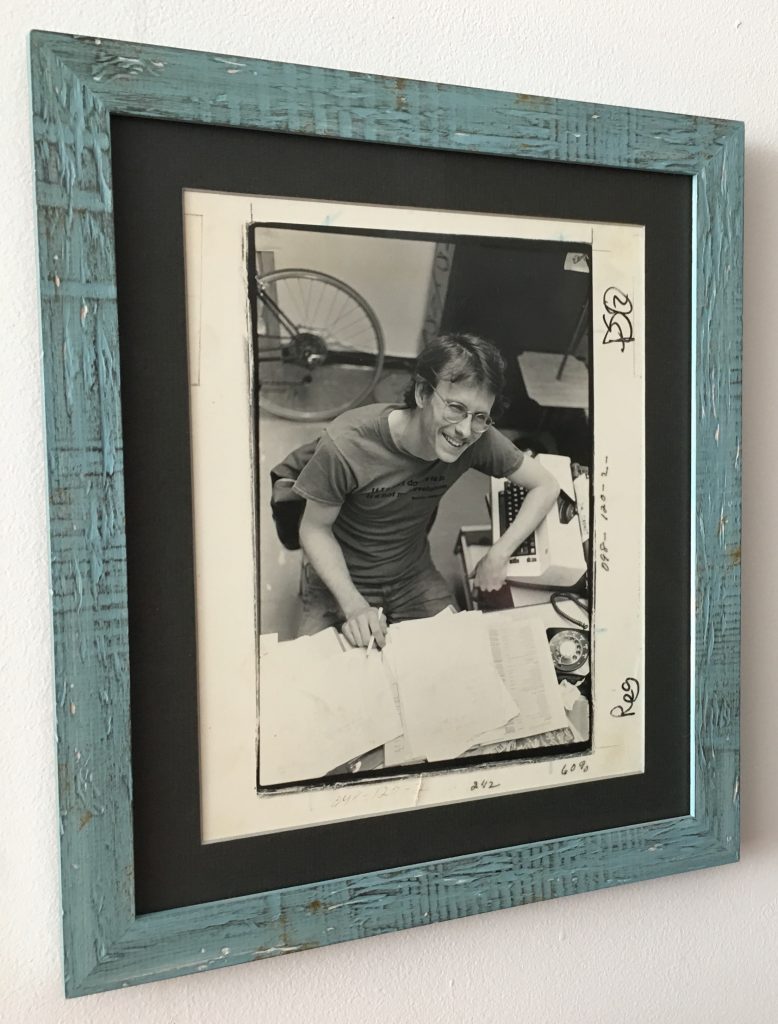

I had an old friend from college named Reg Gilbert who had worked as an intern at the Bergen Record’s news desk (at the time, one of the most impressive newspapers in New Jersey).

When I rewrote the story, it was with professional help, and it was basically perfect: starting with a hard lead that nailed the main issue that emerged in the meeting, inverted pyramid style, clean writing, all in correct AP style. I did not mention my assistance copy editing. Reg’s picture still hangs over my desk.

She decided I would get the position of Warren reporter — the town with the most interesting news.

“But not before the Full Moon” she said. “You should never start anything right before the Full Moon.” So I had to wait a few days to start. It was my first experience of what is called electional astrology — choosing the right chart for the right action you want to take.

An Ongoing Astrology Class

Two or three other reporters in our office covered four towns: Warren Township, Stirling (Township of Passaic), Watchung and North Plainfield. If a word of astrology ever got in the newspaper, it was Ben Franklin who put it there, in some other century. The only point of intersection between our duties as a newspaper and the constellations was in the office itself. Above ground, we were ordinary, hardworking beat reporters; when out of public view, we were stargazers, whether skeptical or not.

There was no questioning the efficacy of astrology, if anyone was tempted, which was unlikely even if you thought it was ridiculous.

She took it so seriously that you would feel stupid not at least paying attention; and from the mere force of her personality, you would have to admit that you might be missing something if you dismissed it. That’s partly because she was almost always right about everything else. Reporters with no proclivity to woo woo (and there are plenty; we are a hardboiled lot) at least had to listen and learn a bit of the jargon.

In the spirit of newspaper reporting, and respecting my boss and beliefs I did not understand, I treated the subject as objectively as I did any other.

Per my training and later experience of working with A Course in Miracles, I also learned that quite a bit is possible in the world that I didn’t think or imagine was. I was after all living in a New Age community, where there was a lot less grounded stuff accepted by my housemates and some truly unusual things happened.

It is best to keep an open mind rather than be dismissive — a quality that has helped me many times as a professional journalist and in many areas of my life.

Flo spread the gospel of astrology throughout the newspaper group via the central office in Stirling where we all came to do final editing and production. She was friends with a man named Jim Kelly, who ran the newspaper group’s production plant.

He was the guy who would come in and take the web offset printing press apart and put it back together if it was broken, to make sure the newspapers came out on time.

He could also fix the computers and the plumbing. He did not seem like the astrological type. But taped to his door was an official-looking sign, typeset in-house, bearing a phrase he had copied from Secrets from a Stargazer’s Notebook by Debbi Kempton-Smith, with whom I would have dinner in an Indian restaurant in Manhattan years later:

Don’t sign. Don’t buy.

Mercury is retrograde.

Mercury isn’t always retrograde, of course. But I can see where to him, as the master of all things both digital and mechanical, it might have felt like it. For Jim to be advertising his endorsement of astrology was more evidence of its veracity rather than of Flo’s role as a thought influencer — but both were true. Looking back, it’s rather funny that for a newspaper group that did not run a horoscope column ever, once, just about everyone was at least fluent in the basics of astro-talk.

As I mentioned, I was assigned to Warren Township, the biggest town with the most news in our area, featuring a brand-new interstate highway running through its north end, and lots of big real estate action.

There, I covered the Township Committee, the Planning Board and the Sewerage Authority, along with writing about traffic planning studies and the politics of major development projects. All writers had to take turns doing “Man on the Street” interviews, writing the ridiculous “People” column and writing police blotters. Marriage announcements were (thank God) handled by Nikki in the central office up in Stirling. She wrote millions of them.

It was a serious job, where we all had to produce about 80 column inches per week of high quality news journalism, get nothing wrong, stay at work late to cover sometimes endless municipal meetings, write fast on deadline nights and the rest of the time, and were paid about $120 each 60 hour week for the privilege.

Our region of New Jersey at the time had one foot in its earlier agrarian and rural environment, and (thanks to Interstate 78) one in burgeoning suburbia and industrial development. It was still possible to feel the place it had been for so long. There were little hints here and there.

For years, two men took turns being mayor. Frank Salvato was a dairy farmer and George Dealaman ran a slaughterhouse. I remember these people vividly 35 years on.

What was interesting about my era at the Echoes was that a new political party had emerged, called the Concerned Citizens of Warren, and it was shaking things up — in particular, getting a grip on runaway development. It was led by a man named Paul Archibald.

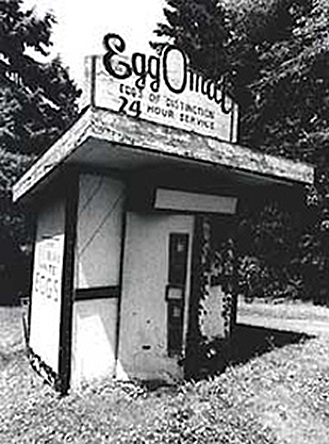

At the far end of Main Street, on the way out of town, standing along the road, there was a dilapidated one of a kind thing called the Eggomat. It was an egg vending machine, which looked hilarious and still worked. It was guarded not by a camera but rather by an intercom, which must have been connected by a cable to the farmhouse behind it. This may have been the invention of the “internet of things.”

Yes, This Was my J School

It was in this environment where I learned how to be a journalist, and also how to read runes and tarot cards, all provided by Flo, who would bring things into the office from her book store.

I added my own contribution to the mystical atmosphere of our gritty little news shop, with its sagging floors, ancient awards hung from the walls, and its heaps of reporters’ notebooks and steno pads from yesteryears stuffed into file drawers and closets in the back.

At the time, I lived at Miracle Manor, a community based on A Course in Miracles, located about half an hour away. A Course in Miracles is a thousand-page course in spiritual psychology and healing first published in the late 1970s. It’s designed to be practiced independently, though several people had formed a community, and in its second year, I got to live there.

A Course in Miracles communities were so rare, we may have been the only one. Ginger — my girlfriend who found the help wanted ad on the kitchen table — came along with me to the Echoes, as we had been working as a writing, design and photo team for years, at our university.

She brought her stylish, down to earth personal ambiance to both Miracle Manor and Echoland. (She is a Scorpio who in winter would wear a striking, bright red full-length wool coat.) Her grandpa Bill was a columnist for the Buffalo Courier-Express. We had both had learned a lot about writing from him.

I loved my job — it was a tremendous privilege to be a working journalist. The fact that it was a town in New Jersey mattered not; I knew I was getting a lesson in the cell biology of civics. I found all that municipal government stuff truly interesting.

Nobody reading the newspaper would have picked up the meekest clue of the mystically infused atmosphere of the office, where some friend of Flo’s might walk in offering rune readings for $3 and the next Mercury retrograde would presumably turn the whole publishing company upside down (it never did). We had the best coverage of the Planning Board, the Sewerage Authority and the Township Committee anywhere. We were good.

My Miracle Flight to Buffalo

Flo could be hard to get along with, but I learned it was worth the effort. Many miracles happened involving Flo — things that went right when they should not have.

One weekend, I had scheduled a trip to Buffalo, where I still had friends and successors-of-enterprise on my former college campus. I planned to take a couple of days off after our stories were filed for the week. But at the last minute, Flo got hung up about certain details in my article about Jell-O wrestling at the high school, and kept me on the phone for an hour doing edits, which pushed me dangerously close to missing my flight.

If I missed the flight, I would miss a meeting on the campus designed to straighten out a political problem in a forthcoming election. I was angry. But, being a student of A Course in Miracles, I decided to at least try to forgive her, and as soon as we hung up, I got in my Dodge Dart and headed for Newark Airport.

All the while, driving along, I was focused on forgiving her, thinking, okay, it’s not a big deal. That’s just how she is. And so on.

Then suddenly I was lost on the six-lane fettuccini of the New Jersey highways. I panicked. Then I was at the airport. Then I was in front of the USAir terminal and saw a sign for parking. There was a parking spot right by the front doors. It looked legal. I parked and locked my car and ran.

However, I had no ticket, or even a reservation; I cannot tell you why, maybe that’s how you did it back then. I headed for security and, mysteriously, got through. This was after some terrorism had created the rule about needing a ticket to go through the security check, but nobody asked me. Then I bolted through the airport, not quite leaping over garbage pails.

Then I was at my gate; well, the gate for a flight to Buffalo for which I had no ticket. Nobody standing there, not a soul. The Jetway was open, leading to the airplane. I walked in and, at the end of the little bridge, stepped onto the airplane and was greeted by a hostess.

“Welcome aboard USAir!” she said cheerfully.

“Hi,” I said, and looked around for a seat. There was a window seat around Row D — the only seat I could see anywhere.

I slipped in, stashed my bag in front of my feet, and tried to shrink my aura to the size of a cricket. I watched one hostess walk up and down the aisle doing a headcount, and another physically counting the boarding passes; I understood this process.

If the two did not add up, they would keep counting and figure out who or what was wrong. Then I watched as they locked the cabin door, knowing that was it: they couldn’t open it except for an emergency. The airplane took off. I made it to Buffalo in time for my meeting.

It was experiences like this that gave Flo a mysterious and meaningful place in my life. There was something between us, and it seemed to involve our respective spiritual paths. By this time I was well involved in my study of tarot cards, and she had personally passed the ancient tradition on to me, by being the person to lead me to the cards, and more significantly, the one who handed me my first deck.

But she was also someone with whom I could practice the principles of the Course: if she got on my nerves or was too demanding, all I had to do was make an effort to forgive her and some miracle would happen. I would add this, however. The Course does not exactly say that you should forgive people. Rather, it teachers you to ask your inner teacher for help forgiving them. You bring the “small willingness.” The great spirit brings the rest.

The Harmonic Convergence

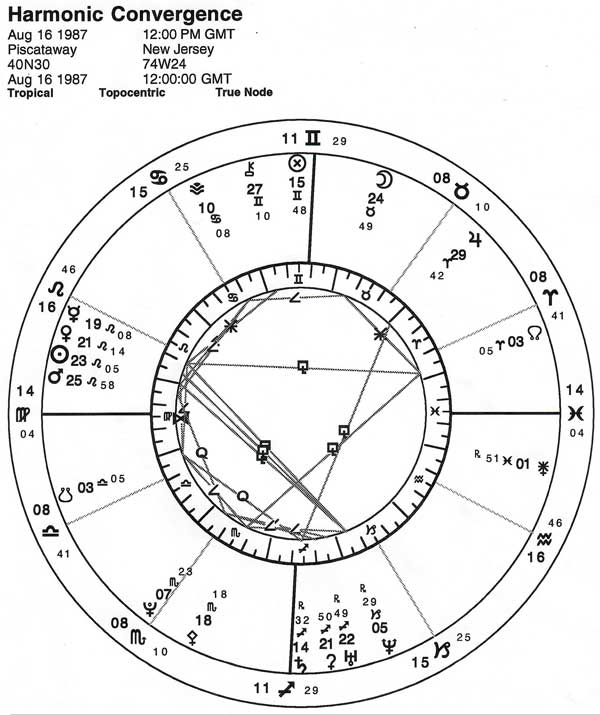

From the era of my life that I associated with Flo Higgins, there is one other event worth mentioning. On that astrological calendar over my desk, there was one day I kept looking at: Aug. 16, 1987. That was the date of the Harmonic Convergence, a worldwide meditation for peace created by Jose Arguelles, author of The Mayan Factor. If there was just one thing I was curious what astrology had to say about it, that was the day. (This comported with my later preference for the astrology of events rather than people.)

Flo knew about the Convergence; she owned a New Age bookstore after all. That her Warren reporter took an interest was evidence that the world was becoming a better place. The other reporters were only meekly interested.

Miracle Manor, where I lived, ended up becoming a hub of this event for central New Jersey, all the way down to Princeton (quite a distance). That’s because an organization called the Holistic Health Association of the Princeton Area (HHAPA) had an event planned but nowhere to host it.

Miracle Manor had a 16-acre facility with a big multipurpose room, a kitchen, 16 acres along a river, guest rooms and a chapel. But we had no event planned.

In typical Miracle Manor fashion, the two merged, and we hosted the HHAPA Harmonic Convergence event, which was so large it made page one of the Newark Star-Ledger, the biggest newspaper in the state.

For those interested, there are descriptions of both that event and of Miracle Manor presented in detail in an earlier book of mine called Light Bridge: The 25-Year Span. That document covers from 1986 up through 2011, with many Planet Waves articles retrieved and presented in a kind of historical sequence.

As for the astrology of Aug. 16, 1986: Once I started casting charts in the mid-1990s, it was one of the first that I cast. It currently hangs on the wall of my office, cast in the first version of the astrology software I use, before the chart was even available in color.

I’m adding it as a graphic; this is not what I was looking at on the wall over my desk. That was a more ordinary calendar with some astrological hieroglyphics. But for the record, I’m including the chart for this pivotal event.

Soon after the Convergence, Flo announced her retirement — or rather, her resignation. I coordinated the writing and printing of a parody called the Echoes-Echoes, which included a feature article called “Making the Most of those Useless Gourds” as part of the autumn supplement. Jim, the Mercury Retrograde plant manager, took care of the printing, and we used company equipment to typeset and publish it.

Then we gave it out at Flo’s “resignation” dinner. It was a big hit.

The Echoes-Echoes contains a running joke about the “astral plane,” to which Flo made continuous reference, as if it was a place as tangible as the town library. As a matter of ordinary discussion, anyone not paying attention to their work was said to be “out on the astral plane.”

I stuck around a couple more months and worked for the new editor, a serious guy about 30 years old named Charlie, who had been with the company since he was a puppy. He promptly warned us how bad what he called “job hopping” looked on a resume (i.e., don’t go out for a soda and get a job with the daily paper), and he wore a tie and sports jacket to work. He wanted us to act and write like proper journalists.

But it wasn’t any fun. He didn’t have the raw, gloves-off intensity and the constant running tirade of cynicism that made working with Flo so excellent, and what was worse, there was no more astrology. Journalism became serious in a boring way. When I headed off to my next job, editor of Kane’s Beverage Week, I brought my tarot cards with me. I brought all I learned from Flo’s campy, gritty, honest approach to community journalism.

And I knew not to start anything right before the Full Moon. After 25 years of astrological practice, I can personally confirm that is good advice.

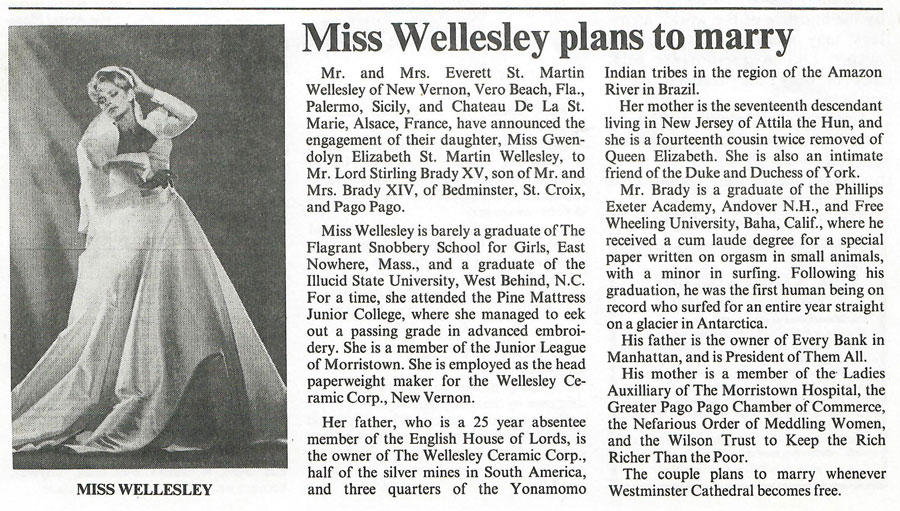

I mentioned that someone named Nikki wrote the wedding announcements from the central office in Stirling. I would see her when I came in to edit before her shift ended on production nights. When we did the Echoes-Echoes parody of the Echoes-Sentinel on the occasion of Flo’s resignation, I asked Nikki to write an announcement about this photo that had found its way into the Warren office. I already had a crush on her because she was so intelligent, calm, sweet and adorable. Then she revealed her streak of comic genius.

Onto New and Different Things: Kane’s Beverage Week

Shortly after Flo resigned — something nobody thought would never happen, or rather, we were certain would never happen — I left the Echoes-Sentinel to become a national business reporter. I brought with me a lot of writing experience, a deck of tarot cards and a basic astrological education. Around the same time, the Miracle Manor experiment ended, and I moved into an apartment in Plainfield with Ginger.

My training in A Course in Miracles would be something I would use every day throughout my life, in every facet of my existence, whether personal or professional.

As for the tools I had been exposed to from knowing Flo, tarot cards seemed the most useful; they are portable, easy to access, and don’t require so many steps to get from the question to some concept of an answer.

Astrology is infinitely more complex, and I could not see the point of it, so at the time, I did not look into it much.

That worked out well, because learning tarot is a great way to study astrology, even if you don’t know you’re doing it. Tarot contains its own symbolism and then through the deck are interwoven many layers of astrology imagery and concept. This includes the 12 signs, major planetary archetypes, and even some combinations of the two.

Tarot contains references from many sources (particularly depending on the deck), though on one level tarot can be seen as a shorthand astrological system. So without recognizing it, by making a study of tarot I was learning astrology.

This fact came to the surface when I began working with The Book of Thoth by Aleister Crowley, which I consider the best book on the tarot. I say this because it’s an excellent study in the most basic levels of the deck — the elements (which are the suits), the meaning of numbers (therefore basic numerology), the identity of the characters in the 22-card Major Arcana, and how each card in that part of the deck relates to every other (through a system called Kabala).

While Crowley is explaining tarot he’s also explaining the foundations of astrology, making this an efficient way to learn both and to leverage one system off of the other. This by the way is the essence of Crowley’s teaching: he works across the various esoteric systems and is for that reason an excellent author to study.

My new job was national business reporter, working for a company called Whitaker Newsletters in Fanwood, New Jersey. I was the editor of Kane’s Beverage Week, an industry newsletter that served executives of major liquor, wine and beer companies. House of Seagram was a big fan of our work and had many subscriptions, which cost $250 a year in 1988. You may have heard of some of the other work of its founder, Frank Kane: he also wrote The Shadow radio scripts, and was a pulp fiction scifi writer.

I also edited Health Professions Report, a newsletter for medical and nursing school deans.

As editor of Health Professions, I was sent to Chicago to cover the proceedings of the American Medical Association (AMA) world congress, as well as nursing conventions in Kansas City and New Orleans. I was once sent to cover a brewery opening in Fort Collins, and had lunch with Auggie Busch III and the Colorado governor.

Looking back, it was an incredible opportunity for a 24 year old journalist.

Wherever I went, A Course in Miracles, my tarot cards and my notebook came with me. I was fully devoted to my work as a journalist, and my work as a spiritual seeker, and I was able to make the connections.

I understood that being a reporter was not separate from my spiritual training. Rather, my “work” was the main place where I would be applying my esoteric knowledge.

One day I was at the National Beer Wholesalers Association trade show in Anaheim. This was capitalism galore, with California beauties pouring beer throughout a football field sized trade show floor. I went to lunch in the Anheuser-Busch free restaurant (all the major companies had them).

On a whim, I spread my tarot cards on the table, and sat there in a business suit doing free readings for people attending the trade show — my first time ever reading for anyone in the public. It would not be the last. I loved it, and I was good at it.

As for astrology — I had no interest, or so I thought.

Onto New Paltz, New York

In the spring of 1989, there was a strike at campuses of the City University of New York. In the Whitaker Newsletter office, I watched on the little television as students were arrested, being dragged kicking and screaming. I recognized they had not had passive resistance training. In that moment, I knew I needed to get back into campus journalism of some kind.

During my years at SUNY Buffalo, I had edited two different campus magazines and the student handbook. I loved covering educational issues. At Whitaker, I was also editor of the New York Education Law Report, but that was not nearly interesting enough. And mostly it dealt with state court rulings that affected K-12 schools.

That spring, I was following the Grateful Dead on tour to a few cities, and at the Pittsburgh show, I met a young lady named Kirsten. A moment later, she introduced me to a tall Japanese psychedelic artist named Mikio, who had hair down to his waist and who was born on my birthday. They both lived in a place called New Paltz.

I went to visit her one weekend, and decided that that was the place I wanted to be. The Paltz was a place unlike any other, with a history and splash of DNA to match San Francisco. It had a State University campus.

I applied to start a masters program midsummer, which is pretty much impossible because the admission period is over. However, someone who had been admitted died in a car accident, and I was given her her space as a student and the classes she was supposed to teach.

I never met her, but some of my teaching colleagues knew her as an undergrad. She seemed like a pure-hearted type and was an excellent poet — someone I would have loved to know. I owe her a debt of gratitude for the many, many unusual events that unfolded as a result of my going to New Paltz. I only know her pen name: B. Wisteria.

When I think about her, I feel a pang of longing, as if I miss an old friend — though I never met her.

My primary goal coming to New Paltz was to study English on the masters level, and write poetry, something I started doing around the time I graduated, and got deep into.

While I was working at Whitaker Newsletters, I self-published my poems in a series of four chapbooks that I printed on the huge copier used to create the newsletters we sent out. I did not know it at the time, but writing poems is excellent training.

If you’re working carefully, you’re thinking about every sentence and phrase that you write; poetry is sensitive down to the punctuation and visual placement of the words. This prepares one for every other kind of writing.

While I did plenty of poetry while I was in New Paltz, I soon discovered my true literary love, which was journalism. Using the publishing model I learned at Whitaker Newsletters, I started a statewide professional newsletter called Student Leader News Service.

The Little Bang, the Big Bang and the Bigger Bang

Like many things in my life, particularly where my writing is concerned, I had no idea what I was getting into when I started Student Leader. I came up to New Paltz in possession of a superpower: a Mac II CX computer, then a state-of-the-art Apple. The only other person to have a comparable computer was a guy named Gil Plantinga, who became the unofficial tech for Student Leader.

I also had a laser printer, then a new technology. Our work looked impeccable (thanks to a lot of training as a designer, from Ginger). I could publish high-quality publications at home.

Student Leader concept was that we would serve as a news gathering and distribution organization that served student newspapers and student governments throughout the State University system.

Pretty soon, we were drawing friends from down in the City University of New York system, who were excellent journalists. Student newspapers down in the city were bolder and more fun. First among those was Meridian, at Lehman College in the Bronx.

I recruited some of my new friends to the project. Pretty soon we had established a news network and could move stories around the state fast; that was never possible before.

During our first semester, Associated Press came to visit and ran a story about the project on the statewide news wire. We were being taken seriously! (I have that, I’ll link it soon.)

I secured New York State Capitol press credentials, and I learned the ropes of the Assembly Higher Education Committee and the State and City University central administrations. And that was it — we were part of the New York State press corps.

I have unusually good luck when it comes to drawing relevant information, contacts and documents to me. Sometimes a little too good, but I choose my assignments carefully.

We had great fun and kept breaking bigger and bigger stories — all of them written in my living room, which had been converted to a newsroom with five telephone lines coming in: catchy ones like 255-2500 and for a fax number, 255-2525, which matched P.O. Box 255, New Paltz. We visited many SUNY and CUNY campuses and got to know the editors of the student newspapers there, spreading the gospel of gritty journalism.

One of our biggest stories, working in concert with Meridian, involved busting the University Student Senate (USS), the City University system-wide student government, for blowing nearly $400,000 on banquets, limos with cell phones, a trip to the Ivory Coast and lots of other fun stuff. That played big in the New York City dailies, which we owned for a week (the news cycle was longer then — three to five days).

Our coverage resulted in articles in the New York Times, the New York Post, Daily News and Newsday, some of which you can read here. It was the ultimate gotcha story, and moreover, it was students minding the affairs of our own business. At the time, this seemed like the big one, but really, it was the Little Bang.

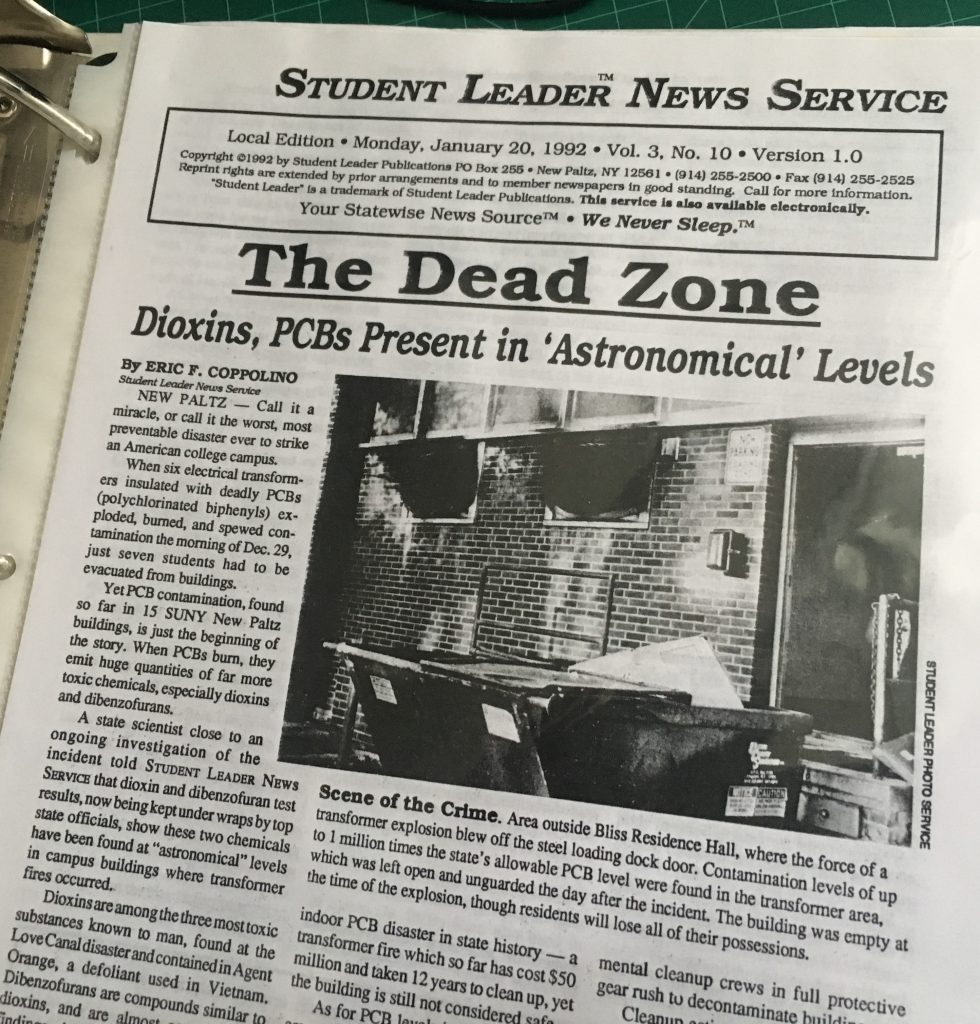

But that turned out to be child’s play compared to what would happen next: the SUNY New Paltz PCB explosions. I’ll summarize those here, though if you want to get to the full story, it has its own website — two words that should never go together: Dioxin Dorms.

The short version of the story is that from the 1930s through around 1980, a class of chemicals called PCBs (polychrloinated biphenyls) were used in electrical equipment worldwide. But the chemicals were defective: they were explosive and more toxic than the manufacturers claimed.

Uses included insulation inside the transformers placed inside of campus buildings at the local college campus. One morning in December 1991, a car skidded off a road outside of town, and hit a utility pole. This damaged the crossbars, the high-voltage wires touched, and an electrical surge was sent into the campus power system.

The PCB transformers were supposed to absorb the blow, but due to defects, seven of them failed, ruptured, burned or exploded, contaminating six campus buildings, the air, the earth and the groundwater.

I knew I had to deal with this on a full-time basis. Soon after, I closed down Student Leader, and continued my career as an independent investigative reporter. Needless to say, I was not using my tarot cards much during this phase of my life; I was covering or rather uncovering the impact of the New Paltz disaster many hours a week.

Soon after, some attorneys representing the Nevada Power Company got hold of my reporting in our local newspaper, and reached out to me. They had information about how what happened at New Paltz had happened many places. In fact, PCB contamination was not just in the campus dorms but also in wildlife up at the Arctic Circle.

Read a description of SUNY New Paltz after the electrical accident

Of the New York Post and the New York Times

Investigative journalism presents a number of challenges: for one, people on both sides of the issue tend to hate you. Readers because you’re telling them they’re going to get poisoned, and the government because you’re exposing this fact. Next, it’s a miracle if you get paid, and while many miracles had happened in my life, at the time, that particular one wasn’t going on. Third, it was psychologically very challenging, as these kinds of stories are dark and sinister.

Uncovering lies means dealing with people who lie, and they are little other than bad juju.But the subject matter was really interesting, and suddenly the story was going national. I became connected with sources who were feeding me documents that proved that General Electric and Monsanto knew decades before that this kind of disaster would happen.

It was around this time that I began reading The New York Post horoscope. Some people knew I liked tarot cards, and someone — I wish I remember who — suggested that I would appreciate what the Post’s astrologer was doing. Normally I would never read a horoscope, just like lots of sensible people. Like most people, I thought they were kind of dumb, and if the astrologer got it right, it was luck.

Right around then, a reporter for The New York Times has been working on a story about my coverage of the New Paltz dorms. I had no idea when or even if the story would run. It seemed too good to be true. But I knew it was possible, because I had already been covered by the Times and every other paper in the city — coverage I sent to Mike Winerip, the Times’ columnist.

On Friday, January 29, 1993, I opened the Post, went to the horoscopes, and skipped down to Pisces, my birth sign. “What happens next will more than compensate for recent financial and personal disasters,” the writer informed me matter of factly. This was the work of Patric Walker, born in New Jersey, raised in England, relocated to Greece, and, as I later discovered, the deacon of the horoscope column.

An hour after I read this, the phone rang. It was a writer from the Times, the polar opposite newspaper to the Post. The writer was Michael Winerip. He was calling to inform me that his article about my ongoing PCB coverage would be appearing in Sunday’s edition — on page one of the Metro Section, no less. It was one of those “Hi, gotta run, bye” kind of phone calls, and he distinctly had the tone: get ready, your life is about to change.

A day and a half later, the story ran. It bestowed not instant success or wealth, but something more precious than both in the life of a reporter: credibility. That, and millions of people would soon find out what was happening in New Paltz. Because the Times is read worldwide, and by the entire newspaper industry, this was a real development. I was no longer just some freak with a Macintosh and a theory. I was about to be a Freak with a Portfolio.

The article was stunning.

“He has a gift for rooting out the disturbing fact from an otherwise orderly pile of documents,” Winerip wrote. “In the tradition of investigative reporters, [he] draws strength from being disliked, blitzing officials with Freedom of Information Act requests.”

Press coverage does not get better than this, really.

Of my prior work, he recalled some of my more impressive moments covering higher education, and added that I was “one of the few people not on the state payroll who understood the state budget.”

Now I suddenly had public acknowledgement, but astrology now had demonstrated itself as well. In one newspaper, someone who knew me pretty well was writing accurate things about my work; in another, someone who didn’t even know I existed was writing arguably more accurate things, putting it all into context.

The Times article became my calling card. From that day onward, a fax of it went everywhere a story proposal went. Every single source, government official, and editor anywhere near the PCB issue now knew the Times was watching my work, and had good things to say about it.

This is quite helpful when people’s main defense against an investigative report about their contaminated building or conniving corporation is to claim the reporter is a nut case. If I was one, then so was the Times, so I was in good company.

Soon, my writing about PCBs, which had expanded in scope to covering allegations of fraud committed by the manufacturers, was appearing on page one of The Las Vegas Sun, a major daily newspaper, then in the Village Voice, and soon after on the cover of Sierra magazine. The Sierra article reached a worldwide audience of environmentalists, scientists and academics. I was also adopted by Woodstock Times, which provided me with a base of operations and an excellent new editor — Parry Teasdale.

Studying Astrology from a Newspaper — and the Ephemeris

In addition to investigating and publishing on the progress of the New Paltz cleanup and the global coverup of PCB and dioxin contamination, I began to track Patric Walker’s column carefully. I started to take in what I could about astrology from the clues he left in his writing: small, basic things like a planet changing signs, Mercury changing directions, or certain aspects he mentioned, often studied sitting on the curb in the parking lot of the local Mobil station where I often bought the newspaper.

Day after day, astrology seemed more astonishing: not merely the accuracy, but the relevance of the points he was making, and his insights into the actions of the people around me. It was interesting that a horoscope column could have this kind of clarity or soundness of advice. But it was also clear, direct writing. His attitude was a bit skeptical, like a friend watching over your shoulder.

Patric was always on your side and whatever you were doing, encouraging you to stand up for yourself. I learned that the message of a horoscope column is not the astrology per se but rather how its ideas are delivered by the astrologer. This is a matter of subjective interpretation, and of the writer’s voice.

Patric was bold, and he could put words together. Your life has you feeling like “a dressmaker specializing in alterations,” he once wrote for Pisces during a rather absurdly complicated period of change.

“What came to light recently has made you aware that there is no use doing things in your usual gentle manner, and the only way to bring others to their senses is by forcing a showdown,” he wrote in the midst of one of the most confrontational weeks of my journalism career, where I had just forced a major showdown.

As I followed Patric in the New York Post, atrology became more intriguing by the day. It also began to rekindle my interest in tarot, which had dwindled a bit when the guys in moonsuits showed up. Through those years, my spiritual point of contact was A Course in Miracles, running in the background. Once it’s in, it’s in.

The whole point of A Course in Miracles learning how to listen to your inner voice, and how to ask for and receive help. It’s not prayer in the sense of a wish list, but of an actual dialog with Spirit. It’s more about listening than asking. The response to prayer often comes in the form of direction.

One night around this time, I was driving from Woodstock to New Paltz in upstate New York, returning from the home of a colleague who was planning to take me to Italy to research Tarot decks in the Vatican’s library. It was a great offer — I love Tarot and grand libraries, and it seemed amazing that the Vatican had a Tarot card collection — and I was also quite determined to visit someplace exotic for the first time.

But this woman was a bit flaky; she rarely came through with her plans. On the way home, I stopped in a gas station and picked up a copy of the Post and opened to the horoscope. It said, “You are obsessed with international travel, but do not put all your eggs in the basket of someone who has let you down before.”

Could a horoscope be any less vague or general?

One day, I had to find out how he did it. This could not be some kind of magic; it was a written newspaper column. My first exposure to astrology had been in a newspaper office; I knew one actual astrologer. I knew that it was a craft. So I went into Esoterica Books in New Paltz, to get the one thing I knew I needed. This happened to be on my 30th birthday, and on a day of special importance related to the New Paltz PCB incident — perhaps a story for another time.

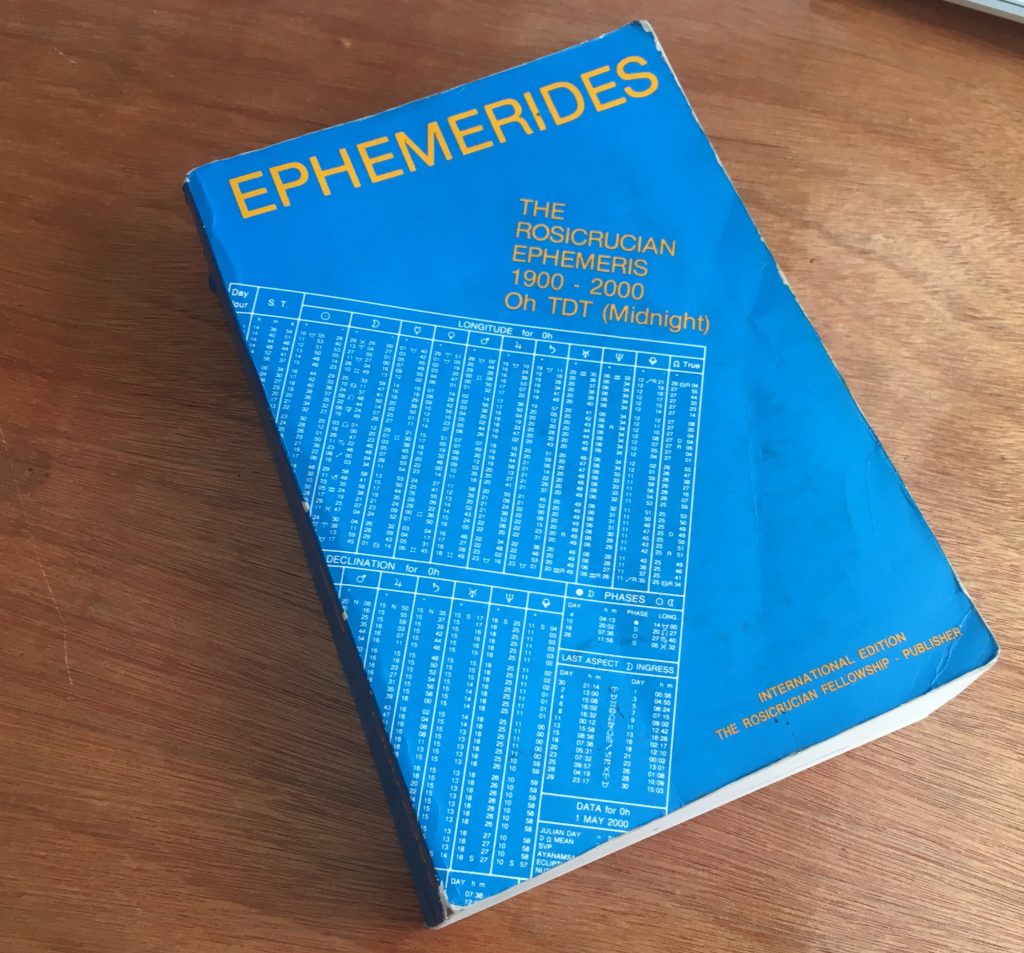

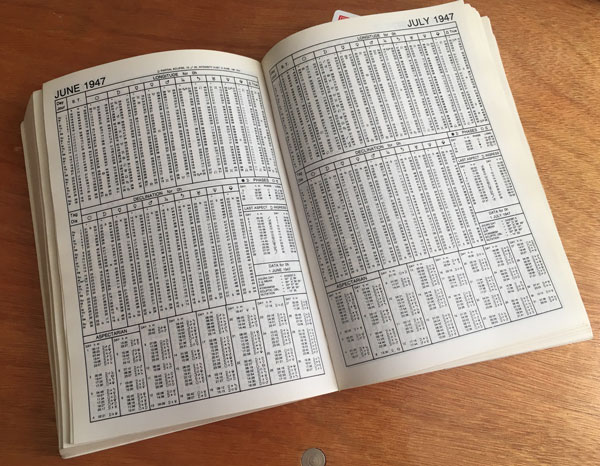

“If you want to be an astrologer,” Flo Higgins had told me once (in her best authoritative Saturn square the Sun tone of voice), “you need an ephemeris.” This is a big thick book that lists the placements of the planets. It looks like a huge trigonometry table, about 1,000 pages, each covered with tiny numbers with the occasional astrological symbol thrown in for relevance. You look up the date in one column, and you see what’s going on with the planets in the other ones. If you know the astrological glyphs it helps a lot.

From then on, when I read the Patric Walker column, I did so with the ephemeris open and a notebook out. The same day, I also acquired a pack of the Thoth Tarot by Aleister Crowley, which is rich with astrological signification and illustrations; this became my astrology picture book.

By day, I proceeded with my work as an investigative reporter, digging ever deeper into the conspiracy to poison the college dorms and the planet. By night, at my new girlfriend Hilary’s house, I would analyze horoscope columns and sort out the Thoth Tarot. Once again, newspaper reporting and astrology were happening in the same place and time.

My articles about environmental toxins began to get more complex, and also more damning. I began taking my own samples and proving that the state was lying. That year, 1994, I won a first-place state award for my investigations.

I had also become involved in a federal First Amendment lawsuit against the campus, which had attempted to ban me from the premises in order to slow my progress covering their toxic buildings. The lawsuit had pressed on for a year.

One day, seemingly out of nowhere, the state threw its cards down on the table and agreed to a $20,000 settlement (and a written apology). The New York Times did a second article. You can find links to all of that coverage here.

In the summer of 1994, one of my articles forced the state to do a partial cleanup of one of the dorms. Under the same extraordinary astrology — which I would not understand until a year later — the summer culminated when my Sierra magazine article came out, documenting the 50-year history of PCBs.

“What happens next will more than compensate for recent financial and personal disasters.” To say the least.

Postscript to SUNY New Paltz

In the year before I was known first statewide and then internationally as a journalist, there were a quiet couple of semesters in New Paltz where I was actually a graduate student, took courses and taught two sections of Freshman Comp.

I read my poetry at public gatherings, and felt one potential direction my life could take, as an author and English professor.

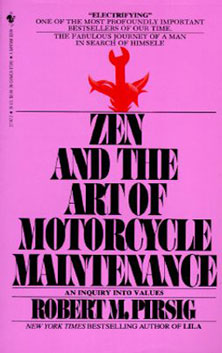

In my Comp 2 sections, the students voted unanimously to ditch the curriculum, and instead read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by R.M. Pirsig.

Much of this book takes place in an English composition section at Montana State University at Bozeman, taught by the author. He has a lot to say about learning how to write, and how to think.

My apartment was in the attic of a little farmhouse at the edge of the woods across from the campus, and I lived there with my two cats, William and Ling Ling. That time of my life is so different from the era dominated by the electrical accident, which is still, sadly, how I remember the campus. The central issue is the administration’s atrocious treatment of students, housing them in dioxin and PCB-contaminated dorms, and lying to them about it.

“You look at where you’re going and where you are and it never makes sense, but then you look back at where you’ve been and a pattern seems to emerge.” — Zen

Of the Jackie Stallone Psychic Circle

Everyone’s seen ads for those Psychic Hotlines on TV. They usually feature a woman, sitting in a room full of candles and wearing a black gown, with the cards spread before her, wisely advising a client on the phone. Have you ever called one? Would you ever? It would never have occurred to me. But one day, I found myself working for one.

When I reached my limit on writing articles about environmental poisoning, it was late autumn of 1994. A few months earlier, I was looking for work, and saw an ad in the Village Voice classifieds, and thought, for a moment, that I might tap my tarot card reading skills. I sent in my resume, passed the “reading test,” and was hired.

I didn’t bother logging in, though. After a few weeks, I forgot that I even had the pass codes dial into the phone system. However, after months of refreshing my tarot skills and studying astrology, I felt like I could at least try, and I needed something else to do. So I dialed the codes into the telephone and activated my account.

Half an hour later, the phone rang.

First I heard a kind of audio trademark, a little puff of music followed by someone saying “Jackie Stallone Psychic Circle.” Then the caller said they wanted a reading. So I read the cards.

It took about five minutes, and the person seemed happy and the reading seemed to help.

I hung up, and then a little while later, the phone rang again, and it was another random person from anywhere, reaching my little apartment in the woods of Rosendale, New York. This apartment was set on the grounds of an old cement mining and refining operation, so the property was surrounded by countless caves and mines, which would soon factor into my astrological studies.

Talking to absolute strangers who had no idea who they were talking to was odd enough. I knew that I could read cards, so I trusted myself to do it. The issue I had was that readings cost the caller $3.95 per minute. My pay was a 10% commission – actually, 35 cents per minute, around $21 per hour if I worked continuously, which seemed unlikely.

I was uncomfortable with the price of the readings; a 15-minute reading cost the client nearly $60, which seemed outrageous, particularly compared to Flo Higgins getting what already seemed like an exorbitant $40 an hour. After taking a few calls, I could tell that the clientele consisted basically of poor people being lured in by television ads late at night.

The next day I called up the company and talked to the manager, a guy named Virgil Curry. He was friendly and sincere, and he knew a lot about the esoteric arts. He asked me real questions. Technically he was my boss. I interviewed him, and explained how everything worked. (After working for Flo Higgins, it was hard to be intimidated by anyone.)

What became obvious was that when a client dialed the phone, somebody somewhere was going to answer and provide them with some kind of advice. So, I decided that it might as well be somebody who could actually do the work honestly — that is, without playing tricks such as frightening people to make the calls longer.

Virgil liked me, I could tell. It made sense that he was a Pisces. He seemed sweet and gentle. In our first call, he made me an offer — in exchange for being willing to work all night, I got my priority rating bumped up to the highest level. Now when I logged on, the calls came through quickly, sometimes with just a few moments between hanging up and the phone ringing again. I would log in at about 11 pm when the ads started running, and would work through the night.

Suddenly I was making $400 a week, a lot more than I was making writing about PCBs, which seemed to run at a loss most of the time. I could afford all the astrology books and charts I wanted. And food and better food for my kitties and that kind of thing. Plus, not having to think about PCBs, dioxins and toxic dorms was an incredible relief.

I spent many nights working like this, studying astrology in the slow moments, and putting to work what I was learning with the constant stream of new clients who were seeking advice.

Pregnant With a Space Alien’s Baby? Not So Much.

One night, I got confirmation that I had made the right choice in taking the job. The phone rang, and it was a very young woman, probably under the legal age to be calling. She was shaken up, and said she’d just gotten off the phone with another operator from my company who told her that she was pregnant with a space alien’s child.

This might seem ridiculous, but I had to take her seriously. No other possibility occurred to me.

I was confronted with a scared person whose faith had been abused by an authority she trusted. And when many people seek advice from an oracle like tarot or astrology, they may, consciously or not, consider it to be coming from a “divine” source, giving it all the more power.

I took her at face value, and asked her basic questions: had she had sex with anyone lately? No.

Did she remember any kind of an “alien abduction,” even in a dream? No.

With those facts accounted for, I read her cards. She was not frantic, just really nervous. She was willing to reason through the situation, and she trusted me enough to help her do that.

It was not difficult to straighten out. For one thing, her own intuition had told her to pick up the phone and call for a second opinion, so she was seeking reassurance of what she probably knew. I saw no suggestion of pregnancy in her cards, much less from some extraterrestrial being. In fact, I saw nothing amiss. I told her this, plain and professional. She seemed reassured, I told her nobody had the right to scare her like that and that I would report it to the phone line manager, who I knew — and the session ended.

This was the first in the genre of “read the cards again because somebody screwed up” sessions. Basically, any prediction that any caller did not like was a screw-up. The prediction would need to be replaced with the idea that we have the power to choose, and the cards can help us see the options. This is good reasoning, and even people who call insisting to be told the future can be reassured by this line of thought.

Many intense situations happened those long nights and early mornings. Once a woman in her 20s called, saying she was facing surgery for breast cancer. She was deeply shaken and fearing for her life, and facing the grief of losing her breasts at a young age. We worked with the cards for a few moments, but mostly we talked. We soon maxed out the 40-minute per-call limit, but clearly, we were not done. The call got cut off. It felt tragic just leaving her like that, and I hoped I had done the best I could.

Then the phone rang. It was her. Against significant odds, she dialed again and reached me a second time, and we completed our session.

Emotional Crisis, Spiritual Crisis, Poverty and Sickness

A number of women called over those months describing the same situation: they were taking care of four or five kids by different men, and the latest man had left them. Others called facing numerous kinds of psychological, spiritual or emotional crises, or poverty, or sickness. Most of the clients were women, driven to pick up the phone by television commercials promising them information, love, money or relief from their pain.

I began to feel like I was working for some kind of bizarre national mental health hotline, and was grateful for my Course in Miracles training, which I soon realized was the foundation of the work that I was doing. The Course provided me with a spiritual foundation as well as provided basic information for how to handle people in crisis.

And from doing three years of therapy, I had acquired some of the tools I needed to carry on the conversation in a helpful way. I knew the limits of my work in certain regards, but also knew that there were real openings for healing if I was willing to be present, pay attention, and use my skills as a card reader judiciously.

There seemed to be times when tarot cards were not appropriate at all. One call came in from a young woman who wanted to know if it was okay if she got sexually involved with a much older, wealthy man who was promising her “diamonds and jewels.”

The obvious implication was that she’d be getting gifts in exchange for sex. I can still feel how excited she was about this, and how she pronounced the words “daaamonds and jeww-els” with a southern drawl. This one threw me. I don’t think I touched the Tarot deck. After pausing for a moment, I asked her if she felt she was doing the right thing, and she said yes.

“Well then, it seems like you’ve made up your mind. Good luck…”

One night the phone rang and the caller asked to speak to Jackie Stallone. I said that this was the name of a psychic hotline, but that she didn’t actually work for us reading cards. I explained that I was just one operator among many and that I was in the middle of nowhere in the middle of night in upstate New York, and that Jackie was nowhere to be found. The woman insisted — paying $4 a minute for the privilege, in 1994 dollars.

The television commercial said that she could speak personally to Jackie. I said she wasn’t here. She kept insisting. I looked around the house. “Well, she’s not in the bathroom, she’s not in the closet,” and so on, which seemed to convince her. I might have thought it was a joke, had she not been so earnest and, well, naïve.

Eventually, I began to work astrology into the sessions. I did that using a little pocket planet calculator that I bought for a dollar at a junk store.

It looked liked a normal calculator, only you would enter a birth date, such as “093066.” Then the little screen would spaz out for about 10 seconds and you would get a row of four numbers between 1 and 12.

These numbers each represented a sign of the zodiac. The four different numbers represented the Sun, Mercury, Venus and Mars, which would fall into one of the 12 signs. These are four of the most basic elements you can use to suss out a personality — what are called the personal planets.

Unfortunately the calculator did not give the position of the Moon, but you need the time of birth for that, since the Moon moves so fast. But having the Sun and three planets turned out to be very helpful, and taught me a lot.

A caller would say something like, “I’m having trouble with my husband,” and I would ask for his birth date, and enter it into the little $1 calculator, listening to them talk. A moment later I would have the husband’s personal planets and make up a little story. “Well, he seems like an intense, somewhat possessive person [Mars in Scorpio] but he’s not really very emotional [Sun and Venus in Aquarius], and he seems to not say very much, though he’s always scheming [Mercury in Capricorn], and…” Usually that would be a close enough description to actually seem plausible, because it was.

When astrology starts to work, it’s a really strange feeling, because you know something that you really have no business knowing.

Reading and Reading Quickly

I got a lot of practice reading for people — and doing so quickly. There seemed to be two tricks to the work. The first was gaining the caller’s confidence in the first 15 seconds, or else they might hang up. Hang-ups would drive the call average down and that could result in getting fired. Unethical readers could start by frightening the client, which is obviously not the right thing to do.

So, really making a clear statement about the nature of the first card or two was essential, which took getting that flash of a message the instant the first card appeared in front of me — and saying the first thing that came into my mind.

Another approach second was asking a clear question based on the cards, and thus getting the person talking about what was bothering them — then actually helping them based on that information. I realized that the cards and astrology were very powerful tools for asking the right questions, rather than just making statements. In other words, you can ask an accurate question and that’s often a lot better for the client than making a potentially accurate statement.

Eventually, I learned to work these two techniques in the opposite order, and built an entire astrological technique on using the chart to make inquiries — which I’ll explain soon.

For the purpose of this work, I developed my own tarot spread, based on a traditional one, called the Celtic Wings. It’s illustrated off to the side. You can read about how to work with it here, and even try it out using this easy tool.

In the process of all this, I was learning a lot about my tools, and about people. If the astrology was interesting, the people were far more so. Working for the hotline was like high-speed, decently paid, midnight astrology boot camp. In all over that winter I must have done 500 readings.

Yet it was strange work, in part because of the diversity of the calls, and in part because I was not accustomed to being so close to the problems that people were facing. And unlike my last project, investigative journalism, I didn’t have to prove anything with reams of documents. I merely needed to make contact, listen and offer empathy and insight.

And I didn’t have to stick my head inside contaminated air vents and take samples of toxins.

David Roell: The Astrology Center of California

In the era when I was working for the Jackie Stallone hotline, I discovered a guy named David Roell, who had an astrology bookstore in southern California. He always had a full-page ad in The Mountain Astrologer, for which I would later be a writer.

This was during the winter of 1994-1995. I didn’t have astrology software; David had a chart casting service that I used copiously. He had every book you could imagine, and I spent most of my money casting charts and purchasing books.

I would do this by phone. Dave had a lot to say. He was lonely where he was, I think around Oxnard somewhere, in a neighborhood without a lot of people. My calls to him would turn into extensive astrology classes.

I would call his toll-free number, 1-800-475-2272, night after night, and get donated lessons the entire winter, each of which went on as long as I could keep going. I learned a lot of astrology from Dave. He explained every book he sold me, and answered my questions on many, many charts.

He had read a lot of books. I am sure he holds the unofficial world’s record in English for reading astrology books. The benefit of that among others is that he could navigate around the history of astrological ideas and traditions, and he took me with me. This was mingled with his love of music, as a listener and as a composer. I think he may have identified as a musician first and astrologer second. There’s been this coincidence where all of my astrology teachers have been musicians and/or composers.

Dave was also a repository of knowledge about Eastern religion, Theosophy, Magick, various matters of psychic affairs, H.P. Blavatsky, occultism in general, ghosts, reincarnation, UFOs and numerous other subject areas, and had something intelligent to say about all of it. In me, he had someone valuable: I was willing to listen and listen well.

More than being an opinionist, which he definitely was, he was a historian and theorist. That is what Aquarius is famous for – coming up with theories. Usually they were interesting; sometimes they were funny – he believed that Porphry houses should be banned. He would not say why.

He also warned me about some untrustworthy people in the astrological community, filled me in on backstory I would have no other way to find out, and explained the political ropes of the profession. Starting way back at the beginning, I had some vital intel and took it under advisement, paying attention but never publishing a word of it. He was the also the source of many contacts for me – he knew everyone’s email dating back to the beginning of the medium, and their phone number. Every astrology journalist should know someone like this.

Then after these conversations, all night I worked for the Jackie Stallone Psychic Circle reading tarot cards. That winter was one of the most interesting times of my life. Mars was retrograde in Leo and Virgo. Pluto was in the very last degree of Scorpio. The Uranus-Neptune conjunction was beginning to drift apart. That winter and spring is one of the few times I am actually nostalgic about.

One day at the end of a phone call, he said, “OK, you’re ready. Hang out your shingle and be an astrologer. Charge $50 an hour. And don’t undersell your tarot. Charge the same for that.” And that was it. He had graduated me. This was some time in early 1995.

I was determined to be an astrologer and clearly it was meant to be. I had seven years of prior preparation, therapy, spiritual training and esoteric studies including tarot prior to these conversations, but still, astrology is not exactly easy and it’s a big responsibility. I am not sure I would have had the confidence after just one year of focused study to do it professionally.

I have always found the astrologers I resonate with to be generous with their knowledge; I could make a long list, and it was those examples that influenced me to model my career the way that I have. But David was a little unusual and never seemed to run out of time for me. Over the past 19 years I’ve called him countless times, any time I had a difficult case or needed to get some insight on an astrological issue.

One year, I made a pilgrimage to my godmother’s hometown in Sicily, I put my feet on the ground, recorded the time, called him and gave him the data and he faxed back one of the most interesting charts I’ve ever seen to my little motel in Piazza Armerina — one of the charts that for me proves astrology.

The Moment of Astrology

This is a method called horary astrology. It is the master art of our trade. It was David who made the point that you can find out anything you need to know from horary astrology, which is the astrology “of the hour,” usually associated with the asking of a question.

He is the person who recommended that I read The Moment of Astrology, a book about horary, which is one of my favorite books, ever.

The book, by Geoffrey Cornelius, begins with the story of a magazine called The Humanist, which in the 1970s had circulated a petition that said that astrology was bullshit. Not just astrology, but horoscopes in particular. The magazine had collected the signatures of 186 scientists (including 10 Nobel laureates), who — without any use of the scientific method or any research at all — had declared astrology unscientific and therefore invalid.

My background was covering scientific fraud. As a writer in that field, my motto was, “Where’s your data?” Well, clearly these 186 scientists had none to offer; they just shared their view. As an investigative reporter, I had made clear in my writing that there is a difference between a scientific finding and the opinion of a scientist. That idea came in handy right then.

In this book, I read that the whole effort to debunk astrology had been orchestrated by the editor of The Humanist, a man named Paul Kurtz. I gasped. I was stunned.

Paul Kurtz had been my first professor on my first day of my first class when I arrived at SUNY Buffalo in 1981: Introduction to Philosophy. When I showed up for university, I walked into his classroom about five minutes late. We he was a good professor, we became friends, and I was an A student.

Paul Kurtz, said Cornelius, was pretty much the nemesis of astrology in the 20th century. In fact, the most successful agitator against our craft in several centuries. And I knew him personally — long before I had a clue what astrology even was. Once again, I felt like fate had placed its gentle hand on my shoulder.