Dear Friend and Reader:

Saturday, June 16, 2012 was the 50th anniversary of the publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. This is the book that not only started the modern environmental movement; it defined the notions of the ‘environment’ or ‘ecosystem’ as we think of them today. Though it’s difficult to believe, prior to Silent Spring, those concepts did not exist in public consciousness.

Today, most people have heard the book’s title, though I’ve been asking around and so far I have not found anyone younger than I am who knows what it’s a reference to.

A marine biologist and avid birder who became a naturalist author, by the time Silent Spring was published, Carson had already written three bestsellers and had won the National Book Award For Nonfiction with her 1951 book The Sea Around Us. Her writing career grew out of working for the publications office of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, where she was editor in chief.

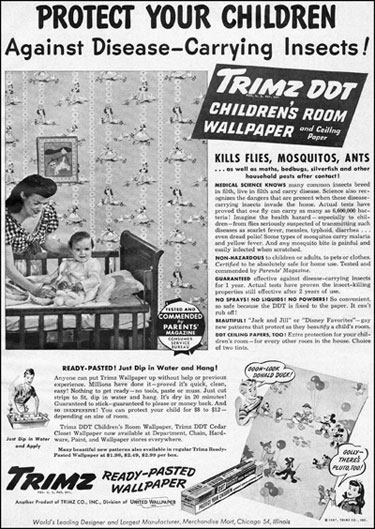

Following up a longstanding interest, she began to focus her efforts on pesticides in the 1950s. This was the era when chemistry was going to solve every problem and save the world from the evils of nature. But Carson was suspicious, and had been collecting data about potential problems since before World War II. Her research resulted in Silent Spring, which exposed the dangers of broadcast spraying of insecticides and herbicides, principally DDT.

The military, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and various industries were busy pouring tons of the stuff onto cities, towns, suburbs, farms and wilderness areas, telling everyone that it was perfectly safe. In one propaganda film, a British public health official is trying to convince an African chief and his tribe that DDT isn’t toxic. At the time it was being used to kill malaria mosquitoes. He has the chemical sprayed onto a bowl of hot cereal, which he then eats. But the chief refuses to accept that the insecticide is safe. (See the sixth film in the queue, “DDT So Safe You Can Eat It.”)

Carson was the first to note that DDT not only killed insects; it acted as what she called a biocide, often wiping out the entire ecosystem where it was sprayed. The interconnection between the levels of nature is what we think of as ‘the environment’.

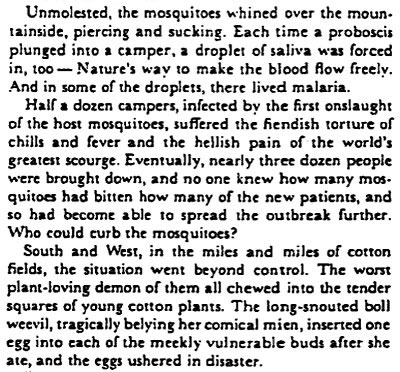

In an effort to kill mosquitoes or gypsy moths, spray airplanes would drop the chemical onto vast forests. Writing with a vivid appreciation of the beauty of nature, Carson describes how contaminated leaves would fall to the forest floor and be eaten by worms, who would then be eaten in large quantities by birds. The DDT would concentrate in the birds’ bodies (through a process called biomagnification), poison them, and then the forests would fall silent — hence the book’s title.

Until this time nobody had explained from a scientific standpoint that all of nature was related in a complex web of life. Though Carson had been making that point in her earlier books, when she pointed out that those webs of life were being murdered by the chemical fogs, people started to notice.

“These sprays, dusts, and aerosols are now applied almost universally to farms, gardens, forests, and homes — nonselective chemicals that have the power to kill every insect, the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’, to still the song of birds and the leaping of fish in the streams, to coat the leaves with a deadly film, and to linger on in soil — all this though the intended target may be only a few weeds or insects,” Carson wrote.

A condensed version of the book was first published as a series in The New Yorker, at the suggestion of E. B. White. Carson had suggested that he write the book; he said she should write it herself. The first segment appeared June 16, 1962, by which time Carson was already suffering from metastasized breast cancer, which had delayed the final draft. The book itself came out that autumn.

Reaction from Government and Industry

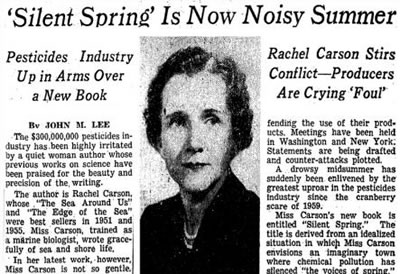

Industry and government response to Silent Spring was immediate and scathing, declaring a kind of national emergency and attempting to discredit Carson as an hysterical nature freak. The response of industry only pushed the book higher up the bestseller list.

“In any large-scale pest control program we are immediately confronted with the objection of a vociferous, misinformed group of nature-balancing, organic-gardening, bird-loving, unreasonable citizenry that has not been convinced of the important place of agricultural chemicals in our economy,” said F. A. Soraci, director of the New Jersey Department of Agriculture. He was right about one thing — clearly Carson was not convinced how wonderful these chemicals were.

As Silent Spring rippled out into the world, the slings and arrows came flying in. She was accused of being part of a cult — that freaky religion of people who love nature. Carson wrote “not as a scientist but rather as a fanatic defender of the cult of the balance of nature,” said P. Rothberg, president of the Montrose Chemical Corporation of California, a manufacturer of DDT. Notably, in Silent Spring Carson never calls for a ban on DDT, only its carefully controlled use when necessary.

“In November 1962, the Manufacturing Chemists’ Association began mailing monthly feature stories to news media, stressing the ‘positive side’ of chemical use,” wrote Frank Graham, Jr. in a 1970 book called Since Silent Spring. “Similar material was mailed to about 100,000 individuals. The National Agricultural Chemicals Association doubled its public relations budget. It distributed thousands of copies of reviews that were critical of Silent Spring.”

Graham noted: “The target of a considerable portion of this material (including ‘fact kits’ which presented the answers wrapped up in the questions) was the medical profession.” In other words, they tried to convince doctors that the chemical was safe — a tactic chemical manufacturers often used years later with dioxin, a waste byproduct of chemical manufacturing, orders of magnitude more toxic than DDT.

Regarding Carson’s book as “an opportunity to wield our public relations power,” Monsanto Chemical Company, a manufacturer of herbicides, pesticides and PCBs, published a long parody of Silent Spring entitled The Desolate Year, portraying nature as evil and depicting the horrors of a world without chemical pesticides. The company distributed 5,000 copies of it to newspaper editors and book reviewers all over the country.

Monsanto had reason to worry. At the time, the company was making most of its money on chemicals similar in behavior, composition and toxicity to DDT, called PCBs, and subsequent lawsuits revealed that the company was lying to everyone about their dangers.

The writing and the message of Silent Spring were so powerful that the book got the attention of then Pres. John F. Kennedy, who referred it to his Science Advisory Panel. They studied the scientific assessments in the book and a year later determined that Carson’s work was based on valid toxicology. This led to a 1972 ban on DDT in agricultural use in the United States — though not until after 600,000 tons of the stuff had been dumped on the environment. Once the DDT issue was raised to public awareness, many other events followed, which helped raise awareness of toxins and begin the process of regulating them.

In 1964, Swedish scientist Dr. Soren Jensen, inspired by Carson’s work, was studying DDT levels in human blood when a mysterious group of chemical compounds kept recurring in his samples, interfering with his analyses. The chemical was so pervasive that his first task was to determine whether it was natural or synthetic.

Finally concluding that it was some sort of artificial pollutant, Jensen set to work to find out what it was. A two-year investigation established that the mystery compound was chlorine-based and chemically similar to DDT. Jensen knew it wasn’t a pesticide, though, because he found it in wildlife specimens collected in 1935, years before chlorine-based pesticides were in general use. All of Sweden and its adjacent seas were contaminated, he discovered; even hair samples taken from his wife and three children showed traces of the compound, with the highest levels in his nursing infant daughter. The mystery pollutant was everywhere he looked.

Eventually, Jensen told me in a 1993 interview for Sierra magazine, “I was convinced that what I had to deal with were chlorinated biphenyls, but I didn’t have the faintest idea where such compounds were used in the society.” Searching the literature, Jensen learned of PCBs’ industrial uses. A German chemical manufacturer provided Jensen with a sample, which he analyzed and found to match the “peaks,” or chemical readings, found in a massively contaminated white-tailed eagle.

“The circle was closed,” Jensen said. “There was no doubt that the unknown peaks came from the use of polychlorinated biphenyls, which I gave the name PCB.” As a direct result of Carson’s work on DDT, PCBs were banned by the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) of 1976, just four years after the ban on DDT. Both chemicals are so persistent in the environment that they still turn up in samples of human blood and breast milk. Through nursing, humans receive some of their highest lifetime doses of these compounds, which gradually build up in the body. Yet the problem with TSCA and its successors is that federal regulators will not allow the words “fetus” or “embryo” into the language of the law.

Attention was, and still is, focused on the outer environment. For example, by 1970, just eight years after Silent Spring and six years after Jensen discovered PCB contamination of the whole environment, even Sports Illustrated was writing about toxins issues.

In a landmark article called Poison Roams our Coastal Seas, Robert H. Boyle wrote that samples analyzed independently by the magazine “disclose that the reproductive process of at least four different fish populations may be threatened by high residue levels of chlorinated hydrocarbon pesticides in the eggs. High levels of DDT residues (a combination of DDT, DDD and DDE) are in the eggs of striped bass from California, from the Hudson River, New York, from the Rappahannock River, Virginia, and in the eggs of bluefish caught off the coast of South Carolina. Moreover, the eggs of the California and New York bass have high PCB residues, an industrial compound that has escaped into the environment by accident.”

Well, I guess that depends on what you mean by accident. Read the whole story here as I told it in Sierra magazine in 1994.

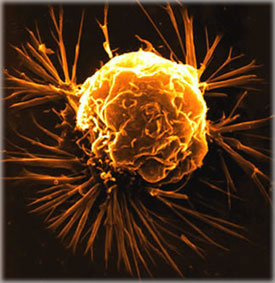

Endocrine Disruptors: The Hormone Ecosystem

Dr. Theodora Colborn is sometimes credited with writing the modern version of Silent Spring, a 1997 book she co-authored, called Our Stolen Future. Colborn studies the issue of persistent toxic compounds not from the standpoint of their impact on the outer environment, but rather their effects on the human endocrine system, which regulates hormones that influence reproduction, emotions and every organ in our bodies. All of these chemicals are carcinogenic, though that’s considered a high-dose effect. At extremely low concentrations — for example, the parts-per-trillion level — the chemicals function as hormonal toxins.

Colborn’s work, developed in the decades after Silent Spring, determined that thanks to DDT, PCBs, benzene-based plasticizers including BPA and many heavy metals, we are all swimming in a sea of hormone-disrupting chemicals. Unlike natural hormones, hormone disruptors tend to be extremely persistent, lodging in the liver and other organs, creating cascades of reactions.

Because a healthy body is so dependent upon endocrine balance, hormone disruptors are associated with nearly every medical condition. These include reproductive issues, miscarriages, birth defects, endometriosis and many forms of cancer.

I reached Colborn this week and asked her thoughts on Rachel Carson’s work. “Silent Spring acknowledged that the entire ecosystem was being destroyed, that DDT was affecting all life on Earth and there was nothing that was not being affected. Carson was using her research on animals that was quite strong,” she said.

“Rachel Carson began to create an awareness that we should have had innately. We became aware of the obvious things around us. Yet we could make these chemicals that we could not see. If humans are going to survive they are going to survive because they’re going to understand what they’re actually doing when they’re fooling around with chemicals that were never in the environment before. It’s taking us too long and too many people too late to realize this.”

Colborn noted that “There are two places in Silent Spring where Carson has just one sentence: I wonder what’s happening to the babies in the wombs of the women who are exposed to these chemicals. If she only had a chance to live three or four more years, she would have caught on to the endocrine disruption and the transgenerational transmission of these chemicals.” The effects of many endocrine disruptors can be passed down for seven generations (scientific validation of the name of the chlorine-free paper product brand, which is based on an Iroquois concept).

Had she lived long enough, Colborn speculated, Carson would have made these discoveries on her own. But she died at the peak of her influence of complications arising from breast cancer in April 1964.

“I myself never thought the ugly facts would dominate, and I hope they don’t,” Rachel Carson wrote to a friend as she finished writing Silent Spring, quoted in the 1980 book Speaking for Nature by Paul Brooks. “The beauty of the living world I was trying to save has always been uppermost in my mind — that, and anger at the senseless brutish things that were being done. I have felt bound by a solemn obligation to do what I could — if I didn’t at least try I could never again be happy in nature. But now I can believe I have at least helped a little. It would be unrealistic to believe one book could bring a complete change.”

This was probably the most erroneous prediction that Carson ever made. Her one book did bring a massive change in the way pesticides were used and regarded by both governments and people. For a time, it even seemed possible that precautionary policy — that is, avoiding danger and factoring in for worst-case scenarios — would replace reckless uses of “economic poisons.”

Rachel Carson’s Astrology: Sagittarius Full Moon

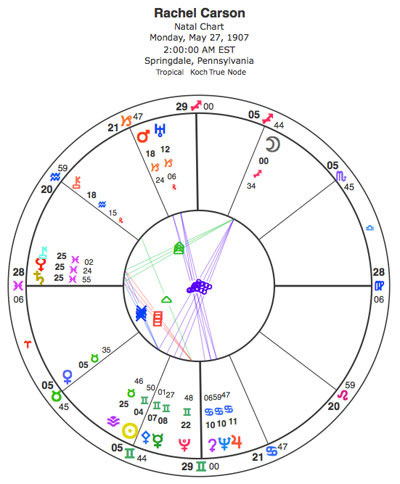

We have Rachel Carson’s birth chart thanks to a data collector named Mark Penfield. The data receives a rating of C, which means “conflicting” or in this case, rectified from an approximate stated time. Though I could not contact him, I checked out Penfield’s bona fides and learned that he’s got a knack for chart rectification, that is, tuning up an approximate time, or working from no available birth time. The chart itself looks functional to me (and I’ve worked with it before — just have not written about it till now), so I’m going to go with Penfield’s data.

Carson was born in 1907 with the Sun in Gemini and the Moon in Sagittarius. She’s a Full Moon baby, which is another way of saying she’s standing in a spotlight and brightly illuminated from within. She’s accustomed to living with contention and polarity, and (as both a Gemini and Full Moon person) had many distinct sides of her nature that she could express.

Gemini almost always bestows a gift for language, and it was the language of Silent Spring that made the scientific findings so compelling. Carson had more than the Sun in Gemini — she also had a conjunction of Pallas Athene and Mercury, which accounts for her precision, her clever strategy and most of all, the political impact of her work. Whenever Pallas is in the scene, look for the political and legal dimension of things. In fact, her words did change the law of the land; she was personally responsible for the banning of DDT and directly precipitated the banning of PCBs.

Finally, she was among the Greatest Generation cohort which was born with Pluto in Gemini. Her words influenced the legal, political and scientific levels of society only because they resonated with the millions — a function of Pluto. All of these Gemini planets are in the 3rd house (even the Sun counts, because it’s just one degree away). That’s the house of writing, with which she was obsessed enough to do very well.

She had her Moon in Sagittarius, which grants both a wide vision and a kind of eternal optimism. Sagittarius is the sign that addresses the cosmic level of reality in a worldly way. Carson could see the large picture — nature itself — and then reflect it back to people in clear words and ideas. Though she would have been unlikely to use the word, the Sagittarius Moon is like a homing device for spiritual themes. Yet her sensitivity and discipline as a writer and scientist kept her from being preachy.

Barbara Hand Clow once wrote that the 4th house is the one that addresses sensitivity to the environment — and in this house we find a cluster of planets in the sign Cancer. That would be extra specially sensitive. Once again we see evidence of bringing her soul into the work. She has a triple conjunction of Ceres (the Earth mother) plus Jupiter and Neptune. It is fair to say that she felt the Earth as a living thing but also as an expression of deity. She never used those kinds of words, though her writing vibrates with the feeling.

Now let’s put the parts together. For example we can see how she was a disciplined scientist (Mercury conjunct Pallas Athene in Gemini) and at the same time she was an empath for the Earth (Ceres-Neptune-Jupiter in Cancer).

Notice how this blend of influences — the planets in Gemini giving the gift of language, and the planets in Cancer bestowing sensitivity and emotional impact — describe Silent Spring so perfectly. All of these planets are deep beneath the surface of her chart. She was coming from the inside out with every word.

If we look at her ascendant, we get a perspective on what a complex woman she was. She has late Pisces rising. In that ascendant is another triple conjunction — this one extremely unusual, comprised of three slow-moving planets that cannot get together in the same place more than every few centuries. And on the day she’s born they are in a less-than-one-degree conjunction.

The three points are Saturn (essential to understand in any chart), Nessus (a Chiron-like centaur planet, dealing with the dark side of human nature and the influence of karma) and Eris (which in Pisces could focus a spiritual search with the power and reach of the Gulf Stream). The presence of Nessus is particularly striking, since it’s so closely associated with consequences. One of its key phrases is, “The buck stops here,” and in many ways the pesticide buck really did stop with Carson. I doubt that one person ever caused more damage to the profits of chemical companies.

Yet there is astonishing tension in that conjunction — the very slow-moving Nessus-Eris conjunction is contained by Saturn like a pipe bomb. It’s a good thing she was so disciplined or she might have exploded. We can infer from this conjunction that she knew she was dealing with vast forces, though she had the gift of being able to focus and make her point. It was unusual then as now for a book to get the attention of the president of the United States, who then takes action. That kind of concentrated impact can have its roots in a conjunction this powerful.

One other thing, of the many placements we could discuss in this chart: she had Venus in Taurus in the 2nd house. To me that says healthy self-esteem, and some confidence that she was making a valuable contribution to the world.

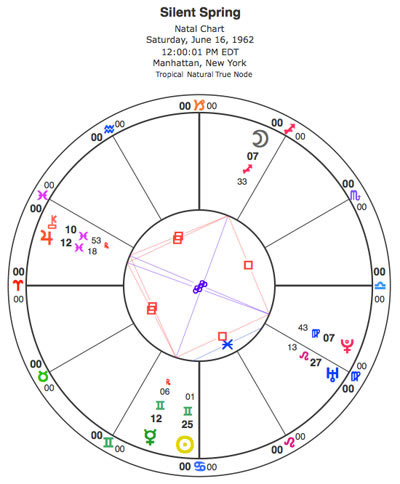

Silent Spring Astrology: The Dawn of the Sixties

Let’s take a look at the astrology on the day that Silent Spring first came to public consciousness, serialized in The New Yorker magazine. That was in 1962, at the dawn of what we think of as the 1960s. This was a time when many revolutionary ideas were brewing, and strangely, it was a time when ideas had impact. This is shown in the astrology by planets in the mutable signs, which are all about ideas. Mutable signs are also movable (as in psychically mobile), and they tend to be receptive, both of which are essential to actual learning.

I’ve greatly simplified the chart to show one aspect structure — a grand cross in Gemini, Virgo, Sagittarius and Pisces (the four mutables) that was in effect the day Silent Spring first hit the streets. Certain elements are fast moving, others are slow moving — and the combination makes a unique chart with real impact.

The backbone of the cross is Pluto in Virgo opposite Chiron in Pisces, one of the distinctive aspects that lasted all through the 1960s. Chiron, to the left side of the chart, is in a conjunction with Jupiter — which focuses Jupiter like a laser and brings it down to Earth. We have an image of applied ethics, or what you might think of as practical spirituality, shown by that aspect.

I realize I keep using the word spiritual in this article, because that’s the theme that keeps coming out of these charts again and again — a deep connection to life and existence, yet with its roots in the unseen world. Carson was a mystic in the deepest sense of the word, and her ability to bridge the worlds of mysticism and science is something that today we would describe as ‘shamanic’. Yet she is not cobbling these things together as if they were separate; rather, they are emerging from the same deep inner place.

Then there is Mercury (the green kid with the horns). As in Carson’s natal chart, both the Sun and Mercury are in Gemini. Mercury is making many aspects — the closest being a square to Jupiter (the orange 4); and then squares to Chiron (orange key) and to Pluto (red golf tee). Mercury is retrograde, which challenges some of the conventional wisdom of this condition. This is definitely the beginning of something that will have huge impact. And as you might expect of a mutable grand cross, there is going to be some controversy (what The New York Times described as ‘Noisy Summer’).

How do we interpret Mercury retrograde? For one, this is the chart of the pre-release of the book, and Mercury retrograde indicates a revision process. The actual book comes out several months later. Next, the impact was unexpected; Carson never believed the book would have the kind of impact that it did. So we have Mercury in full-on trickster mode, in Gemini and retrograde (notably, just a few days before it stations direct, acting like a spring). This also supports one of my key phrases for Mercury retrograde — the truth comes out.

Last, the Sagittarius Moon passes through the neighborhood that day, meaning that Silent Spring, just like Carson, came out on the eve of the Sagittarius Full Moon. The publication chart has many resonances with Carson’s natal chart, which is a way of saying something that proved to be true — Silent Spring was a true reflection of her life’s work.

The chart demonstrates the power of a grand cross, or planets placed at the four corners of a square. And, published just prior to Uranus ingressing Virgo and the start of the Uranus-Pluto conjnction (exact for the first time in 1965), the book became one of the intellectual foundations of the 1960s era.

Its publication is credited with starting the grassroots environmental movement, which led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Yet while Silent Spring directly led to the banning of DDT and PCBs, there are many new chemicals that are just as bad or worse when it comes to hormone disruption. One of the most problematic is BPA, or bisphenol-A, which finds its way into nearly every bite of food that’s wrapped or contained in plastic. There are brominated biphenyls, very similar to PCBs, used as flame retardant — and these are nearly ubiquitous.

“Where would we be without Silent Spring?” asked Theo Colborn, whose work picked up where Rachel Carson left off. “Probably in a much bigger mess.” That is saying a lot, particularly given that the environmental movement seems to be at a low ebb right now, while the tide of toxic compounds is rising every day.

Yet that may change. Chiron is back in Pisces, and Silent Spring is about to have its Chiron return. Says Dale O’Brien, “Mythically, Chiron was the defender of nature, rising to action to single-handedly drive off the wild centaurs who were destroying the environment for their carefree enjoyment. In the chart of Silent Spring, Chiron in Pisces conjunct Jupiter indicates that Silent Spring has become perhaps the main inspiration for the ecology movement. ‘Movements’ in my astrological opinion can only happen when outer planetary bodies are in a mutable (moving, moveable) sign. Chiron’s return here can revitalize the ecological movement.”

Lovingly,

![]()

Additional writing and research by Carol van Strum. Photo research by Sarah Bissonnette-Adler.