Dear Friend and Reader:

When Mohonk Preserve wants to expand its land holdings, they often depend on the services of a man named Robert K. Anderberg, a former trustee of the Preserve and currently general counsel of the Open Space Institute (OSI). [The Preserve recently lost another case involving an attempted land acquisition; see related story.]

Anderberg’s land acquisition playbook includes purchasing the mortgage out from under a neighbor and foreclosing on them, setting up front companies to do transactions, buying land from someone who doesn’t own it, claiming land by adverse possession (squatter’s rights) and setting the Preserve’s neighbors up for costly litigation, sometimes pitting them against one another.

There are many examples of this over the years where Anderberg acted as land acquisition agent for Mohonk Preserve. Several of them focus on one particular property formerly called Smitty’s Dude Ranch.

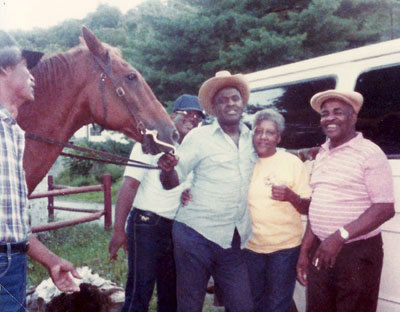

Once owned by Wilbur Smith, it was a mecca for hippies and nature lovers, who would turn out in droves every weekend and hang out naked by the stream. But by the mid-1980s, Smith was in foreclosure and was facing the potential auctioning off of his land. The end of an era was drawing near. Mohonk wanted the land and was watching carefully.

When I interviewed Smith for Woodstock Times, he told me that at the time, he was exhausted from repeated attempts by the Mohonk Preserve to take his property or prevent him from using it. He didn’t have the money or the skills to defend himself, so he sold the ranch to Karen Pardini and Michael Fink, his old friends who were frequent visitors to Smitty’s. Ultimately they saved him from foreclosure and made sure that he got at least some money from the sale of his property rather than none at all.

In 1985, while Smith was still owner, Seward Weber, the new executive director of Mohonk Preserve, filed his last quarterly report of the year. “A major challenge and opportunity faces the Preserve in that the first and second mortgage holders on Smitty’s Ranch plan to foreclose on that property about the middle of December,” Weber wrote to his board of trustees.

“Bob Anderberg is studying ways the MP might obtain this land which I am sure everyone realizes is of critical importance to us since it is contiguous, large (over 200 acres) and contains the most attractive stretch of the Coxing Kill including a waterfall,” he wrote.

At the time, Anderberg was a trustee of the Preserve and had been since 1981. His role, as it is today, was land acquisition.

In his report, Weber explained why Mohonk should own Smitty’s. “Most of the land is undevelopable and should come to the Preserve just because it would round out our boundaries in that area.”

Weber proposed that most of Smitty’s Ranch should be turned into a camping area that could produce income for the Preserve. Then he wrote, “There are perhaps 40-50 acres along Clove Road suitable for three or four large house lots which, if sold, could cover a substantial fraction of the purchase price of the property.”

Weber explains that Anderberg has a “promising” approach to getting the land, by forming a separate corporation funded by “a few wealthy individuals” who would loan it the money necessary to buy the land at auction.

“Once it owned the property, the corporation would donate the undevelopable areas, including the Coxing Kill frontage, to the Preserve and develop the land on the road into lots with deed restrictions or conservation easements” to ensure that building proceeded “in a manner satisfactory to the Preserve.”

The loans would be paid back and Mohonk would own part of Smitty’s and develop the rest. That is to say, the Preserve’s plan was to develop much of the property into a camping area and private homes.

The plan did not work out that way. Smitty was able to delay the procedures and two years later Pardini and Fink bailed him out of foreclosure. But Anderberg would persist in his efforts to get the land. He had by that time left the Mohonk board, taken a job as general counsel for Open Space Institute, and was also general counsel for a small conservancy called Friends of the Shawangunks, which serves as a land-acquisition agency for Mohonk.

In 1994, Anderberg, working with Mohonk’s surveyor Norman Van Valkenburgh, approached Smitty’s ex-wife Mary Lue Smith and told her that she still owned a portion of the ranch, the deeds for which Smitty had kept in her name.

“I realize all this may come as a surprise,” Van Valkenburgh wrote to her in making his offer, knowing she had conveyed all her land to Smitty’s second wife Ruby decades earlier.

They offered to pay her $5,000 for what they described as 30 acres of “landlocked” and “inaccessible” property, leading her to believe this acreage was different from the land she had sold years earlier.

In her testimony, Mrs. Smith admitted she was surprised someone thought she still owned land, but she agreed to meet with Van Valkenburgh. He went to her home with the quitclaim deed and a check for $5,000, accompanied by Anderberg.

According to Smith, Van Valkenburgh described the lawyer and top official of Open Space Institute only as a notary who would witness her signature.

In an affidavit, the 75-year-old Smith testified that Anderberg and Van Valkenburgh “misled and tricked me into having me execute the paper” for a parcel that included road frontage and was part of the larger property she had conveyed years earlier.

With the Smith quitclaim deed in hand, Friends of the Shawangunks then attempted to “prove” Mary Lue Smith had retained an interest by pointing to a copying error in the 1965 deed, which omitted a description of the 30 acres.

But Mohonk Preserve’s documents indicate that the Preserve had been aware of the clerical error for 20 years. In particular, a July 5, 1974 letter from what was then the Mohonk Trust to Smitty warned him of the error in his deed, stating, “one or more pages have been left out.” They urged him to file a corrective deed with the county.

Then two decades later, Anderberg tried to get the land based on that mistake. Judge Vincent Bradley said it was “patently obvious” the deed was in error. Bradley in his decision said that Pardini and Fink had standing to bring a fraud claim.

Around the same time, Anderberg arranged for the purchase of another portion of the former Smitty’s Ranch from someone else who didn’t own it.

In a March 24, 1993 memo from Anderberg to Van Valkenburgh, and Glenn Hoagland, Mohonk’s executive director, Anderberg writes, “One of the landowners on Rock Hill, a Gloria Finger, is interested in selling a portion of her acreage to the Mohonk Preserve.”

The land that Anderberg chose to purchase from Finger (from among three different options), however, was always part of Smitty’s and was now owned by Pardini and Fink. Van Valkenburgh, the surveyor, drew a line around the approximately 75 acres at the west end of the ranch, filed the map with the county clerk and the Planning Board, and the Preserve paid Finger $82,000 for land worth more than $2.5 million. She lost none of her own land in the transaction.

With the backing of its title insurance carrier, First American Financial of Santa Ana, CA, the Preserve then sued Pardini and Fink for that property, ultimately losing the lawsuit after nine years of litigation.

Anderberg had tried other tactics to acquire the Smitty’s Ranch property. For example, When Smitty still owned the ranch, Anderberg recruited Anita Gehrke, Fink’s sister, to help acquire the land.

Gehrke was friends with Smitty and Anderberg felt that could give him an advantage. “He knew Smitty hated him and Mohonk, and therefore would never sell the property to either of them,” Gehrke said. “So he came right out and asked me to front for them — to purchase it with their money. I decided there was no way I could do this and deceive Smitty.”

When Fink came up with the money to make the purchase directly from Smitty, saving him from foreclosure, Gehrke got a call from Anderberg, who was furious at her and her brother — about which she has testified at trial.

“I want you to call your brother and tell him that I’m going to be breathing down his neck the rest of my life,” Anderberg said to Gehrke in a phone call. “I’m going to do everything in my power to take his land from him. Tell him to watch what he’s doing. Any mistake he makes, I’m going to be watching,” she recalled him saying.

“He told me he had coveted the land his entire life and that he and [a wealthy actress who would fund the project] were going to put houses down by the stream on sensitive wetlands areas,” Gehrke said.

That’s the same area that Seward Weber described as “most attractive stretch of the Coxing Kill including a waterfall.”

In one other well-known case, Anderberg was attempting to acquire land owned by Louise Haviland adjacent to the Preserve. Haviland had purchased her land directly from its prior owner, who was holding a private mortgage for her.

Anderberg personally purchased the mortgage, and after he did so, took advantage of a provision allowing him to call in the note — that is, to demand that Haviland pay him back all at once. When she could not do that, Anderberg brought a foreclosure action against her and her tenants, ultimately taking possession of the land and selling it to Mohonk.

On Thursday, I called up the Land Trust Alliance, a national organization of land conservancies based in Washington, DC, and asked it if its code of ethics approved of these kinds of practices.

Robert Aldrich, the communications director, told me, “Land trusts don’t do that, to the best of my knowledge. The whole thing about land trusts is that it’s a voluntary agreement between the land owner and the land trust.”

I guess Mohonk has its own definition of “voluntary.”

Lovingly,