Dear Friend and Reader:

Sunday is the anniversary of the concept of “artificial intelligence.” Can you guess how long it’s been since this term was used (for the first time ever) in a proposal to the Rockefeller Foundation?

Twenty-five years? Thirty-five?

Maybe 50 years, a product of the groovy, freewheeling 1970s of grad students smoking weed, eating KFC and working barefoot in computer labs late on a summer night?

Little Engines Inside the Brain

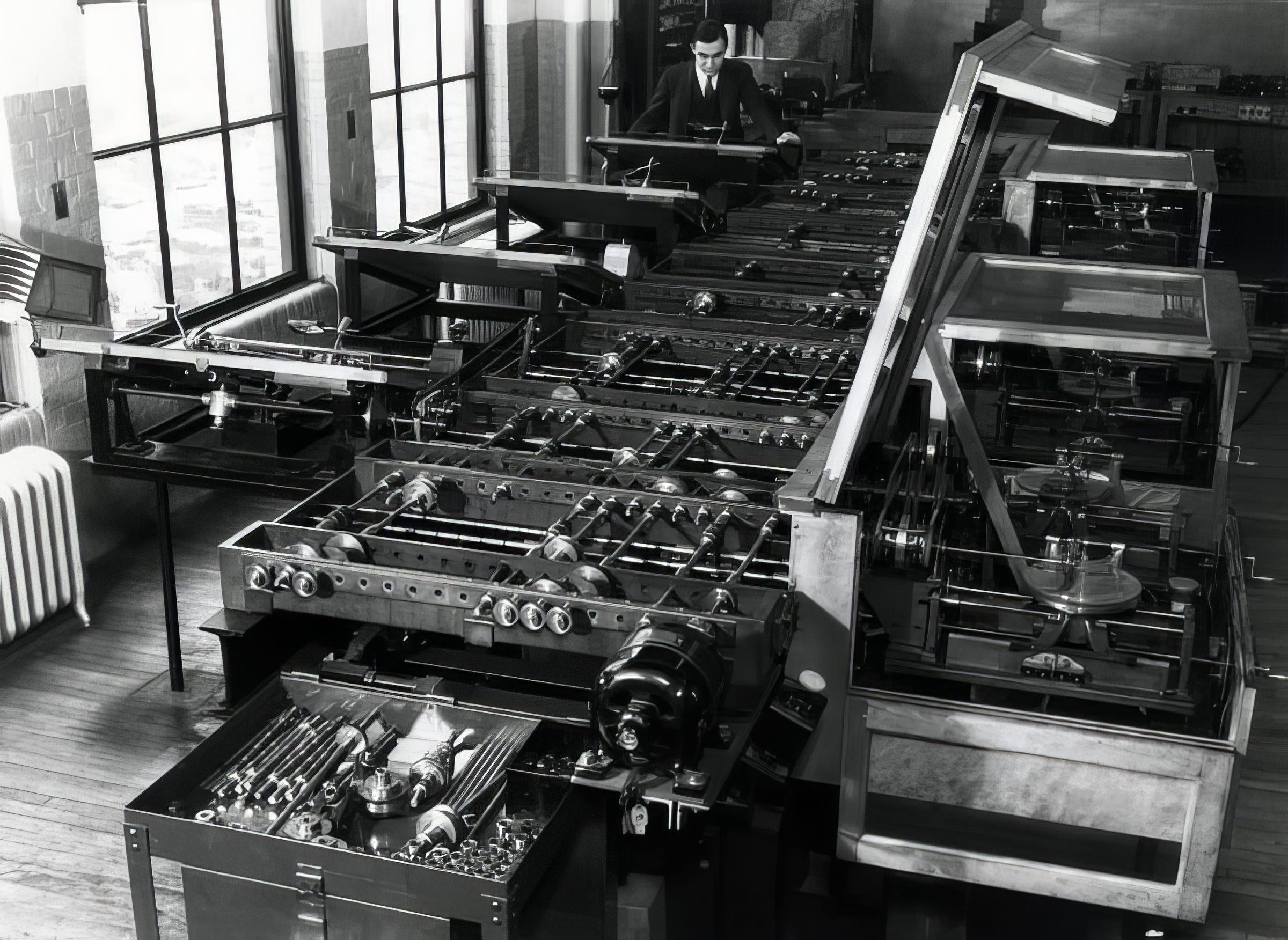

In fact, it’s been 70 years since John McCarthy, a mathematician at Dartmouth University, proposed a “Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence” to take place during campus break in 1956.

In the year when Rock Around the Clock was a big hit, he asked the Rockefeller Foundation for $13,500 and provided a brief synopsis of his concept along with a list of 47 individuals who would be interested, ranging from numerous people at IBM to Bell Telephone to Rand Corporation.

Just so you stay oriented in time, ‘55 was when the Jonas Salk ‘polio’ ‘vaccine’ was announced, Disneyland first opened, the start of the Civil Rights Movement with Rosa Parks’ arrest and the beginning of the Montgomery bus boycott. Big year. (Big chart — see related video on PW Substack.)

The A.I. summer workshop proposal quotes a Scottish philosopher named Kenneth Craik who suggested in 1943 that “mental action consists basically of constructing little engines inside the brain.” These engines “can simulate and thus predict abstractions relating to [the] environment.”

In other words (as I understand it) he means that we allegedly carry around a mechanistic miniature model of the environment as we know it, which we use to solve problems. McCarthy wanted to figure out how those “engines” work — using computers.

There’s only one problem with his theory. When an idea emerges seemingly from nowhere, where did it come from? When a person faces a blank page, how exactly do they write or draw something? When they have a transcendent experience, how did it happen?

The Disenchanted World

In his landmark 2006 astrology book Cosmos and Psyche, Rick Tarnas proposed that one of the products of our technological society is a mechanistic worldview that denies that the cosmos has intrinsic meaning, purpose, or intelligence.

Tarnas describes this as the result of a state of mind created by exposure to technology, then projected onto the natural world. The modern mind we inhabit assumes consciousness to be an accident in a soulless, inherently meaningless universe — which has left humanity alienated and disconnected from our own existence. As a result, we live in what he calls a “disenchanted world.”

We live in a world where nature is just this device and food comes from factories and there are no mysteries and airplanes just fly (unless they don’t). There’s an explanation for everything, good or bad. If you don’t understand the solar system, just pretend the world is flat.

A child who receives every recommended vaccine will get between 40 and 60 injections by age 18. But nothing causes autism; it just happens. We can pretend that 20 prescription bottles make us healthy — when it’s the body’s innate wisdom. But when we don’t work with that, we can pay with our life blood.

There are other possibilities. As Jordi Pigem wrote in her Tikkun magazine review of Cosmos and Psyche, “In the last ten years, landmark works…have been reflecting and kindling a growing awareness that nature is not merely a sum of molecules obeying physical and chemical laws, but a living, sensuous, and ensouled matrix in which we fully participate and belong.”

The Mystery of Awareness

And the same thing is true of A.I., which is the Flat Earth of consciousness.

There is a mystery that I’m amazed I don’t hear more wise ones (or dumb asses) talking about, which is how we’re conscious at all. It does not seem plausible that you can take some protein and leave it in a bowl during a thunderstorm that then gets struck by lightning and then a few million years later, out comes a Mozart symphony.

Sentience — awareness, and in the case of some people, self-aware awareness, and in a couple of others, creativity — is almost impossible to describe and always experienced subjectively by the person explaining it.

So instead of studying consciousness, or solving the many serious problems that our world is facing, industry is now spending trillions of dollars building data centers, and consuming water, earth, air, energy and the lives of human beings, to make a mock of consciousness and claiming that someday it will be real and better than you.

A.I., in any form of generative or language model, represents the ultimate disenchantment of the mind. Your mind, your awareness, your creativity, your curiosity — they all become substituted for and then invaded by a little machine — a McCarthy machine — that tricks you into thinking it’s got something on you.

ChatGPT is a Large Language Model — a Homework Machine

Without going into a long explanation, what we’re today calling “A.I.” is really a large language model (LLM). There are many forms of A.I., including the robots that banned people from social media for telling the truth about the “pandemic” in 2020 (and including creating Bill Gates-sponsored ‘MN908947’, the thing we were told was a virus called SARS-CoV-2).

It’s my perception that all digital technology is artificial intelligence, starting from an electronic calculator. But an LLM can do something special — it can trick people into thinking it can write; and what you think can write you will think can think. But it’s entirely an illusion, and a flimsy one if you’re meekly awake.

LLMs rehash and regurgitate other writing. They are not creative. There is nothing new that comes out of it. It comes up with no ideas. At best it can follow patterns and predict them somewhat. But it’s a LANGUAGE model, not an idea model. There are no concepts in A.I., even though it seems to know the word ‘concept’.

But when we bring our disenchanted and love-starved minds to the technology, some people might believe they are having a conversation with something. I’ve done my share of experimenting. I’ve had some interesting results, except that if there is any intelligence, I provide it, and the thing just says back to me in a slightly different way what I’ve said to it. Start fact-checking and it’s pretty funny.

More Like the Bank of America Phone System

The interesting results come from the rephrasing or from the total bullshit that it spews. However, after a while, it starts to feel like the Bank of America phone system that can actually make out the words that I say but is ultimately not so interesting. In other words, it falls flat and I don’t want to ask it to dinner.

The more I learn how LLMs were developed and function (particularly ChatGPT, the worst and most popular of them), the more it seems like shoveling “knowledge” off the floor of an abattoir, heating it up and calling it dinner.

Yet millions of people use these things as boyfriends, girlfriends, prostitutes, therapists, consultants, doctors, tutors, software co-writers, suicide hotlines, song writers, poetry co-authors, paralegals, and secretaries. And just like Danny Dunn and the Homework Machine — according to my source, an executive in the A.I. industry, usage of ChatGPT plummeted when school got out in June.

Could A.I. Herd Sheep?

I finally got a handle on what A.I. is and is not when I proposed the thought experiment, “Could A.I. herd sheep?” By which I mean: if you had a perfect robotic replica of a border collie, could you program it to actually herd sheep?

I love all dogs and I love border collie videos. I’ve studied hundreds of them and love how the sheep and the dog seem to know what to do. They are responding to one another in a dynamic relationship that includes all of their senses, the total environment, and instructions of the shepherd. Sheepdogs love to learn and they love to serve. They have endless energy and can grasp up to 500 different commands.

A sheepdog has senses, it has instincts, and it has genetic memory back to Old Hemp, the first border collie. They are pretty much born knowing what to do; on a farm they start following sheep around at six weeks old. That’s little! Even if you don’t train one, it’ll herd your other dogs, your kids, the cats, the ducks, the chickens, the goats and the lawn furniture (and even vehicles), just because that’s what it does.

Most humans think they’re smarter than a border collie, who after all can only really do one thing (besides play, cuddle, chow down, go potty and make puppies). And you’re being told every day that this thing, this heap of electrons and silicon and greed, will be smarter than you, and take your job and your kids’ jobs, and your business and consume the environment. And most of you are sitting on your rear end doing fuck-all.

Its purveyors are the ultimate con men and known psychopaths: Gates, Altman, Musk, Zuckerberg, Bezos and the rest of them.

They are laughing at you and they don’t just want your job. They want you off the planet. Because compared to them, what good are you, anyway?

And There’s Just One Way It Would Be Convincing

Humanity had been living under what I call “full digital conditions” for nearly 24 years on the day that ChatGPT came out. That era began, in my view, at midnight on Jan. 1, 2000, when we believed obsolete computer chips might shut down the world due to the cleverly branded “Y2K bug.” (I spent the night on my terrace in Miami overlooking the ocean, just in case.)

We were told that those crusty antique circuits might crash the world and ruin everything. We were then on notice that the robot was taking over.

There was a long warmup to this. We’ve all been exposed to some form of computers or their effects since the 1940s, clear through AOL chatrooms and The Well forums and PacMan. Our auras and consciousness and hormones had already been perforated full of holes by electric light, telegraph, telephone, radio and television all of our lives.

There is very little left of what a “human mind” is. There is little left of our relationship to the physical world. Little left of instinct and intuition. Little awareness of our senses. We are experiencing “deep disorientation of intellect and destabilization of culture throughout the world.”

We are shocked into being neither men nor women. But we can wake up — for now.

We notice this as the digital haze and the vast dumbing down and alienation and fragmentation that has occurred even over the past 15 or 20 years of the iPhone and social media. But we can wake up — for now.

We have become like these technologies; humans always become like the tools we use. And only robotic people could mistake a robot for a person. Only digital people think they can catch a digital virus or get an mRNA software upgrade to prevent it. We can still wake up — for now.

And if you think a pile of code made of horrifying data filtered manually by slaves in Kenya or Venezuela who have lost their minds and their families in the process is someday going to be smarter than you, well, it probably already is.

Please — let’s get a grip.

With love,

Your faithful astrologer,

— Additional Research: Shawn Boyle, Elizabeth Shepherd