Dear Friend and Reader:

Astrology is based on the premise that the shape of the solar system reflects the shape of consciousness. If that’s true, the edge of the solar system would represent a boundary or edge within the psyche, a place where familiar territory ends and the unfamiliar begins. Over the years, this boundary has moved gradually outward. For as far back as anyone was looking at the sky, the boundary was Saturn, the most distant visible planet. The edge moved outward with the first discovery of a planet — Uranus, in 1781, and with that discovery, the age of science and industry had officially begun.

Next came Neptune, which was finally observed to be a planet in 1846. Neptune for its part was a strange discovery — Galileo was the first to see it, way back in 1612, though neither he nor numerous astronomers who followed him actually understood what it was, even though they noticed it was moving. Such is the elusive nature of Neptune.

After its discovery in 1930, Pluto was the furthest known object orbiting the Sun. It was discovered by accident, when astronomers were busy looking for something much larger, something they’ve yet to find.

Over the years, different astronomers had theorized that there were swarms of small objects beyond Neptune, though by 1992, only Pluto had been found. Most astronomers accepted that it was the outer edge of the solar system. There didn’t seem to be a lot of interest in searching, either. There was no grant money available for the project; it was not as glamorous as studying the known planets. At that time, a lot of attention and resources were going into the Cassini mission to Jupiter and Saturn, as well as to Hubble space telescope projects that involved gazing out to the edge of the universe.

Jane X. Luu, then 29 years old, was doing postdoctoral work in astrophysics, collaborating with Prof. David Jewitt at the University of Hawaii’s observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. They were researching small objects in our solar system, such as comets and asteroids. (One theory about this possible new region of space was that it served as a reservoir of comets.)

They had a question: why did space beyond Pluto seem so empty? In the true spirit of science — curiosity — they decided to look around.

“To us it was of scientific interest,” Luu recalled in an interview last week. “In terms of prestige, we had never wanted to study any planet. Grants are easy. Why study something that lots of other people study? We were going to do things that nobody else wanted to do.”

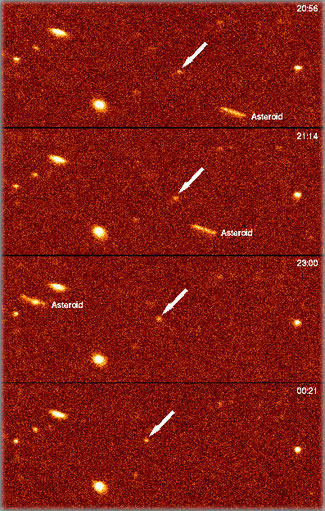

So, they spent their time peering off into the edge of the solar system, looking for anything that was moving. Mauna Kea is an ideal ground-based observatory because it’s sitting on top of a dormant volcanic mountain 4,200 meters above sea level, where the skies are often clear, and where there’s minimal light pollution or smog. Plus, it’s a smooth mountain, so there’s relatively little atmospheric turbulence — the bane of astronomers everywhere. They were using the University of Hawaii’s 2.2-meter telescope, a dependable old beast that had been in operation since 1970.

On the night of Sunday, Aug. 30, 1992, just before 11 pm local time, they pointed the telescope toward the southeastern skies and focused on a faint object. In fact it was so faint, it’s amazing they saw it against the backdrop of the stars. Over the next 90 minutes, watching on a monitor connected to a digital image captor, they noticed that the object was moving — which meant that it wasn’t a fixed star.

Jewitt and Luu had discovered the first-known object orbiting our Sun beyond Pluto. After 62 years of being the presumed edge of the solar system, Pluto’s reign was very quietly over. However, it would take a long time for the news to spread. The object they discovered was not especially large, and these particular astronomers are not media hounds.

The discovery was given the provisional designation 1992 QB1 — a technical reference that notes when it was discovered, and that it was the 27th object found in the second half of August of that year, nearly all of them asteroids of various kinds. (The second centaur planet, Pholus, had been discovered earlier that year, and the third, Nessus, would not be discovered till 1993. Centaurs are small planets located inside the orbit of Neptune.)

1992 QB1 has a nearly perfect circular orbit, which means it’s very stable. (The stability of its orbit is evidence that this region of space is not the origin of comets — they probably come from a region further away.) QB1’s orbit is nearly parallel to the solar equator, which takes it around the Sun in just over 289 years. That’s about 39 years longer than Pluto takes to orbit, though Pluto has a wildly elongated path, which meets the plane of the solar system on a steep angle.

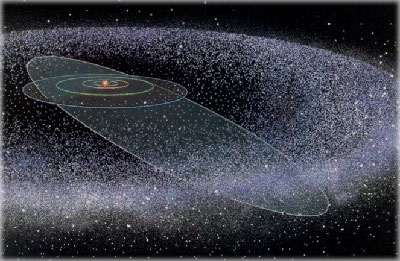

Because it was beyond Pluto, 1992 QB1 was also the discovery of what became known as the Kuiper Belt, named (or misnamed) for Dutch astronomer Gerard Kuiper. QB1 was the observation that demonstrated that there are indeed objects beyond Pluto within our solar system. If there was one, there would be more. There are about 1,000 known today, and Jewitt has predicted that there are as many as 70,000 — probably a conservative estimate based on an actual calculation.

Imagine the Kuiper Belt as a plane extending into space, similar to a ring of Saturn, though surrounding the Sun, out beyond all the larger planets. The discovery represented a radical step in the understanding of the solar system, though its significance isn’t fully appreciated. Among astronomers, many other discoveries get more attention (Eris, for example). Studying these small bits of planetary matter give us a glimpse into the early history of the solar system.

Among astrologers, 1992 QB1 seems to get the least attention of any minor planet. This is in part because the minor planets are not a popular topic in astrology, and even among astrologers who specialize in the new discoveries, QB1 leaves most of them without a starting point because it doesn’t have a name. The names of newly discovered planets almost always come from the astronomers (who don’t generally ‘believe in’ astrology, or think about it much). Yet astrologers depend on these names to help them suss out the meaning a new planet might contain.

Jewitt and Luu had proposed the name Smiley, after the fictional character George Smiley in the spy novels of John le Carré. Smiley is a kind of anti-James Bond — a quiet, disciplined espionage agent rather than one always running around with his gun drawn. But the name had been used on a main-belt asteroid honoring Charles H. Smiley (1903-1977), who was chairman of astronomy at Brown University. Jewitt and Luu did not propose another name, and they have no plans to.

When other bodies were discovered with orbits similar to QB1, they started to become known as the cubewanos, a pun on Q-B-1-ohs. This is some insurance that 1992 QB1 will always be its name. Once its orbit was confirmed and it got a place in the Minor Planet Catalog, its proper name became (15760) 1992 QB1. This always reminds me of Asteroid B-612 from The Little Prince.

Last week I asked Jane Luu if she would share some impressions about her now-famous discovery.

“A lot of people don’t like it, because it started all the trouble for Pluto,” she said. The discovery of QB1 led to many other astronomers looking for objects in the Kuiper Belt, and one of them — Eris, discovered in 2005 — led to Pluto being reclassified as a Kuiper Belt object. “They should think of it as a new frontier of our solar system. It’s just like exploration way back in the 1500s. It’s about mapping new worlds.”

I asked how they financed the project. “We did it by lying and stealing, the usual way things are done,” she said. “We didn’t get any money for it. We would get telescope time to do other projects, and we would use it to do this. We’re good astronomers; we publish a lot and we’re productive, so nobody could accuse us of wasting resources.”

The region of space that Jewitt and Luu discovered was named for Gerard Kuiper (1905-1973), who in his writings referenced the possibility of a swarm of objects in the outer solar system.

“Kuiper anti-predicted the Kuiper Belt,” Luu explained. “He said it would be gone by now. It’s near Pluto and he thought that Pluto was going to scatter everything away. It was all conjecture. He had no numbers to back up anything. He was just guessing.”

It seems ironic that someone who predicted that something would not exist got that thing named after him. “Most people would be happy,” Luu said. “He got something for nothing.”

To correct this, it’s sometimes called the Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt (or in England, the Edgeworth Belt, though you rarely hear this), adding the name of Kenneth Edgeworth, an Irish astronomer, economist and engineer. In the 1940s, he proposed that there would be a disc of icy bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. “Edgeworth was obscure,” Luu said, “but he did not anti-predict it, like Kuiper.”

Why wasn’t the Kuiper Belt discovered sooner? It took 62 years from the discovery of Pluto, during a phase of history with increasingly spectacular telescopes. “These things were always out there, but people didn’t look for them,” Luu said. “People are not good at finding things they don’t expect to see. What you look for you will find. But sometimes it takes a bit longer than you expect, if it exists.”

Now, many of the most interesting new discoveries are found in the Kuiper Belt. Some are more of the nature of Pluto (called plutinos, with orbits around 250 years) and many others are of the nature of QB1 (the cubewanos, or classical Kuiper objects, with orbits closer to 290 years or longer). Plutinos are named for underworld deities. One example is Orcus, named for an Etruscan [ancient Italian, pre-European] underworld god who predates Pluto. Cubewanos are named for deities associated with creation and resurrection (Quaoar, a Native American creator god, is an example).

There are other categories, which are sorted by how many orbits the smaller planet makes compared to Neptune. For example, Plutinos orbit twice for every time Neptune orbits three times. There are other categories with other resonances to Neptune.

Whatever the math involved, David Jewitt and Jane Luu proved one thing: that space is not empty beyond Pluto; there’s something there. For astrologers, so invested in what these things mean symbolically, this is rich territory. Or it should be, anyway. Most people’s consciousness stops at Pluto, if it even gets there, which is a significant limit, given the level of fear involved. One irony is that many astrologers don’t believe in the minor planets. Yet the discovery of QB1 led directly to the reclassification of Pluto as a minor planet, complete with a minor planet catalog number — now known as (134340) Pluto.

Beyond Pluto — Beyond the Edge

I’ve been developing my own impressions of QB1 since 1998, when I was given an ephemeris by centaur specialist Robert von Heeren, who I met when I was living in Munich. He didn’t share any ideas about QB1, just a folder with a stack of printed pages that contained the ephemeris he had calculated himself. [You can see Tracy Delaney’s version here, on Serennu.com.]

For me it was news enough that something existed outside the orbit of Pluto. So let’s start there, since it’s a reference point. Each time a planet is discovered beyond something that’s been the long-established edge of the solar system, we experience a paradigm shift, both in our understanding of the planets, and how they work astrologically. History turns a corner. There also seems to be an extension of the presumed limit on human potential.

Mythologically, Pluto is the Roman god of the underworld. His temples were rarely visited by anyone; he was not a popular figure. As the lord of death, he was portrayed as a kidnapper, who traveled under a cloak of invisibility, a power granted by his helmet.

Astrology usually associates Pluto with the topic of “death and transformation.” Many would consider this a polite statement. Everyone who has lived through a Pluto transit consciously knows that they can be challenging. Indeed, they can be devastating, though we become deeper, more soulful people. As minor planet specialist Martha Lang-Wescott has said, we often miss Pluto transits when they’re over.

In history, I associate Pluto with what I call the Death Works era. The mechanized, chemical-infused death orgy known as World War I preceded the discovery of Pluto by about 16 years, though once Pluto was discovered, things really got cooking. Hitler came to power just three years later and turned genocide into an industrial process. When he was done, Stalin took over and outdid him with the gulag system and many, many more murders.

The rest of the 20th century was pretty much one long war; just naming a few, there was Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia and then Pol Pot’s genocide; there was the “Cultural Revolution” in China (the wide-scale enforcement of orthodox communism); there was a long massacre in Central America and a simultaneous one in East Timor; there were the genocides in the Balkans, there was Bush War I, and an ongoing, seemingly endless war in Africa. The 21st century began with the Sept. 11 incident, which was used to propagate wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. As Noam Chomsky wrote in The Culture of Terrorism, the way to impress Congress is to show them how many people you’ve killed; then you get funding to kill some more.

I don’t blame Pluto for this, though I think that Pluto represented for many people a limit on their consciousness. The limit involved (and for many still involves) the idea that death is the ultimate power, and could be used to get anything, or to gain any advantage. In this toxic belief system, death is the end, it’s the scariest thing, and whoever wields it can feel like God, or at least a god (and not such a creative one) for a while. Death and all the anxiety around it are often substitutes for sex, for love and for a conscious, willing sense of transition. Pluto can represent obsessive forces, and one manifestation is an obsession with death.

Psychologically healthier people have a more functional relationship to change, and to growth, other themes that Pluto represents. Yet even for them, the shadow side of Pluto can be frightening, because it involves investigating the spaces in ourselves that we’re taught to deny, and to be terrified of. Then gradually we integrate the fear of change, and the changes themselves. Through this process we evolve; we can learn to center ourselves in soul consciousness. Yet most people go kicking and screaming.

There has to be a better way. Chiron, discovered in 1977, did a good job of beginning that conversation of a better way; it was the first planet ever discovered that became associated specifically with the healing process. Chiron is also associated with holistic consciousness. Chiron, the “inconvenient benefic,” is gentler than Pluto, and it’s more consciously associated with healing and transformation rather than death and transformation.

Power in the style of Chiron is what you gain from going through your challenges consciously, and what you gradually accumulate as you address your sense of wounding, and develop the power to heal yourself (and possibly assist others). The gradual development of Chiron as an astrological tool was a big step on the way to what 1992 QB1 represents, which is a conscious, preferably willing, process of change. Chiron has taught us a lot about Pluto, and I think 1992 QB1 will have a similar role.

Researching the earliest notes I have on 1992 QB1, I found this comment in an article called Worlds Beyond Neptune, published on Planet Waves in 2003: “QB1 may have associations with the Phoenix-like process of arising into new incarnations within our current lifetime, which often happens as a result of near-death experiences or with the experience of ‘ego death’.”

There’s a lot here about letting go of fear, which is part of every healing process. QB1 shows us that there’s something on the other side of what we’re afraid of, and of the fear itself. Our prior model of the solar system seemed to be saying that there was nothing on the other side of Pluto, of death; last stop, game over.

When Pluto later came to represent what some astrologers call evolutionary process, its reputation improved slightly, though it still seemed to stand for an involuntary imperative. As many have noted, one reason why Pluto transits can seem so scary is the feeling of not knowing what’s on the other side — or fearing that nothing is there.

This new discovery whispered that there was more, and that it was worth letting go of the fear, and I think that QB1 shows a way of doing that. In the chart, think of it as pointing the way beyond your perceived limits about death, which remains a thought so terrifying to most people that they cannot even consider it. Now in the metaphor of the solar system, we have something in the model that says there is more; that there exists something beyond this perceived edge, which we can access if we want.

As I began to explore that idea, I began to understand QB1 as representing anyone who would help people move through processes where this kind of transformation or release was happening. I associated it with those who help people be reborn at the end of their lives — that is, an advanced kind of hospice work. There are some practitioners actually doing this now — though the work is controversial, because it defies the medical establishment, the hospice industry and the funerary industry.

Midwives as well seemed to be involved in the process of birthing new people, and taking women over the transition into a new phase of their lives, which is often like a form of reincarnation. Midwifery is a profound service, and a sacred trust. Midwives guide women through what is in truth a near-death experience, and if it goes well, a baby is born and the mother is reborn.

I was also familiar with the work of Betty Dodson, who developed what she calls orgasm coaching: consciously helping women learn to orgasm (something more necessary than you may think). I began to associate QB1 with certain kinds of sexworkers, the ones who understood that they were doing a service to humanity through their work. This came into focus during a reading for a client in Paris who had 1992 QB1 exactly in her ascendant, and who was designing an evolved form of prostitution with a focus on helping people liberate their sexuality. There’s a need in the world for well-trained sexual surrogates, who would help people past their inhibitions, phobias and fears — and there are people who very quietly do this for others.

What all of these had in common involved taking people over a threshold, so I started to associate 1992 QB1 with the thresholder. As I developed the idea in my fictional stories, the thresholder began to emerge as someone adept in all of these methods of healing and transformation.

Their actual role is to guide people into self-awareness, which is another way of saying into relationship with themselves. I call this process coupling. This is not about coupling with another person, but rather that of becoming acquainted with, and friends with, and lovers with, the inner alien with whom we live.

These ideas meshed elegantly with a subtle, egoless (nameless) planet orbiting silently outside the realm of Pluto, off to the edge of the solar system. Thresholders show us what’s beyond the edge, taking us into new territory and introducing us to the dimension that exists there. One day Dale O’Brien, familiar with my ideas, wrote to me and said the name is obvious. 1992 QB1 is your cue to be one.

It would make sense that 1992 QB1 was discovered on the first degree of the zodiac — the Aries Point. Aries is the sign of “I am,” though the Aries Point connects us to a collective reality. Indeed, 1992 QB1 relates to experiences, fears and inevitabilities that we all have in common. We all cross the threshold of the birthing process, then we do it over and over again. Many of us do it with help; assistance really is necessary here on Earth, with all its adversity.

If we look out at the current political landscape, it’s easy to see how this core, essential human material is harvested into a commodity, used against us, sold back to us or forced on us. This can only happen if we don’t take ownership of what’s within us; if we’re afraid to encounter the edge, and lack the faith that there’s something on the other side.

This is less likely to happen with those familiar with themselves, and who have taken the step toward meeting their inner stranger, that being who lives on the other side of a psychic boundary. You could say that QB1 represents the truth that there is life beyond the body, and beyond whatever you’re going through now.

Lovingly,

I am reading this in 2023, although it was written in 2012, and it amazes me that these fantastic educational informative explorations by Eric have no comments! Well, until now.

I’m also amazed. Were the old comments deleted? This is a brilliant article. Particularly from the perspective of the post Covid world. I will now be including 1992 QB1 in my chart investigations.