By Eric F. Coppolino

Lies Of Our Times | St. Louis Journalism Review

Edited by William Schaap

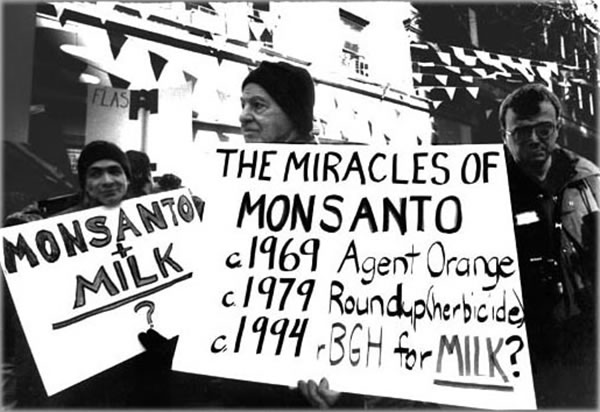

This is an article about how lies become the truth. You may be familiar with the work of Dr Peter Montague, editor of Rachel’s Health and Environment Weekly. In 1991, Montague was sued by a Monsanto scientist, William Gaffey, for libel after reporting a U.S. government finding that the scientist had falsified cancer research for the company. This article is the story of the libel suit. After years of legal battling, with the help of some of the nation’s most effective citizen activists and anti-dioxin lawyers, Montague began to get on top of thing, and then Dr Gaffey died. The story of his fraudulent studies lives on in infamy, as does Monsanto, the world’s leading purveyor of biotechnology. Thanks to my editor at Lies Of Our Times, William Schapp Esq., and my research assistant, Hilary Lanner, as well as Carol Van Strum, Paul Merrell, Esq., Rexford Carr, Esq. and others.

The article that led to the legal action ran in the March 7, 1990, edition of Rachel’s Hazardous Waste News (RHWN), a weekly newsletter published by the Maryland-based Environmental Research Foundation, which Montague heads.

The portion of the article dealing with Monsanto’s dioxin health effect studies cited as its main source a February 23, 1990, internal Environmental Protection Agency memorandum by EPA scientist Dr. Cate Jenkens, alerting the agency to allegations that the research was fraudulent.

Jenkens attached to her memo a portion of a legal brief from an unrelated dioxin contamination lawsuit against Monsanto, from which Montague also quoted. The brief accused Gaffey of concealing the cancer deaths of nine dioxin exposure victims in his study.

The study, which was published in the journal Environmental Science Research (Vol. 26, 1983, pp. 575-91), was co-authored by Judith Zack, another Monsanto scientist. Known as the “Zack-Gaffey study,” it is one of three Monsanto studies conducted in 1978 and 1979 that have been sharply criticized for alleged fraud in methodology and use of data. The three studies were key to substantiating denials of adverse health effects of the Vietnam era herbicide Agent Orange due to its containing dioxin, and have helped form the basis for the prevailing notion now accepted by the mainstream media and much of the public that dioxin is not the wide-scale health threat it was once thought to be.

These three studies have been reported on or published in Scientific American, the Wall Street Journal, Science, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), and other publications generally considered reputable.

Missing Data

Gaffey has testified that he possesses none of the data or research to prove that his study is valid, and claims that Monsanto has the information. Monsanto, in turn, said that the data are in the hands of Gaffey’s former attorneys, Coburn and Croft, who are currently representing Monsanto in this case, and who, Montague’s lawyers say, failed to turn over the data to Gaffey’s new lawyers. Monsanto has become directly involved in the case because Montague’s lawyers are seeking Gaffey’s data and additional information from the company’s files that they believe would prove that the Zack-Gaffey study is fraudulent, as alleged.

While Monsanto is resisting court orders to turn over its files to Montague, numerous documents which emerged in other litigation against the company lend support to the allegation that the study contains manipulated, misleading data. One is a 1984 internal Monsanto memo about the Zack-Gaffey study written by Marcie Strauss, a company official, which lists the names of the dead workers and attempts to account for observed discrepancies in the Zack-Gaffey study. For example, Strauss attempts to explain why some workers were counted as deceased in one of the Monsanto studies and as alive in another. In the Strauss memo, Monsanto denies allegations that the study was fraudulent or the data manipulated.

The three studies concluding that dioxin does not cause cancer, including the Zack-Gaffey study, were conducted in 1978 and 1979 and then released by Monsanto one at a time between 1980 and 1984. They all relate to a 1949 chemical accident in Nitro, West Virginia, that involved an explosion in a pressurized chemical reactor that produced 2,4,5-T, one component of Agent Orange. The Nitro accident exposed hundreds of workers to the herbicide, which Monsanto acknowledges contains small amounts of dioxin, an extremely toxic chemical byproduct of the production of 2,4,5-T.

Dioxin Health Effect Denials

Monsanto used the Zack-Gaffey study to support a 1980 claim that Agent Orange exposure does not cause cancer. At the time, Agent Orange and dioxin were at the center of numerous national controversies, including the Love Canal disaster, Vietnam War veterans’ lawsuits against government and industry, and citizen lawsuits again spraying national forest lands with 2,4,5-T. The EPA was on the verge of canceling the 2,4,5-T product registration because of health concerns, while at the same time the Veterans’ Administration was engineering its now well-documented coverup of the Agent Orange health effects.

“Monsanto Company today reported that no apparent relationship exists between TCDD, the toxic dioxin contaminant in ‘Agent Orange,’ and the cause of death of 58 employees exposed to it during 2,4,5-T herbicide production at the company’s Nitro, W. Va., plant,” the company said in an October 9, 1980, news release about the Zack-Gaffey study.

The same study was presented by Gaffey at an October 1981 environmental science symposium. It was then published in an issue of Environmental Science Research devoted to the symposium proceedings.

It did not become public record that the Zack-Gaffey study had been challenged as fraudulent until the legal brief quoted by Montague was filed in 1989 in a lawsuit titled Kemner v. Monsanto. The claim was based on Monsanto documents that emerged during the Kemner lawsuit, which dealt with a dioxin-tainted chemical spill in Sturgeon, Missouri. Eighteen months later, Jenkens, the EPA official, wrote her memo, which, along with the attached Kemner brief, was sent to Montague by two separate sources, one of whom worked for the EPA.

“For years, industry scientists have been claiming that there’s no evidence that dioxins cause cancer in humans,” Montague wrote in the lead to RHWN No. 171, for which he now faces libel charges. “Now there is mounting evidence that such claims rely heavily on studies that are fraudulent…. A scientist with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says Monsanto falsified data in important studies that Monsanto used to support its claim that dioxin does not cause cancer in humans.”

Montague went on to note that, “In fact, excess cancers have occurred, but it appears that the data have been manipulated to hide the facts.”

Montague then quoted the 1989 Kemner brief Jenkens attached to her February 23, 1990, memo: “Zack and Gaffey deliberately and knowingly omitted 5 deaths from the exposed group and took four workers who had been exposed and put these workers in the unexposed group, serving, of course, to decrease the death rate in the exposed group and increase the death rate in the unexposed group.”

In the same issue of RHWN, Montague also attacked other dioxin studies, including a study produced by Monsanto by Dr. Raymond Suskind and V.S. Hertzberg that was published in JAMA (Vol. 251, No. 18, 1984). Suskind and Zack co-authored a third published Monsanto dioxin study (the Zack-Suskind study) relating to the Nitro incident.

A year after the newsletter was published, Gaffey filed his suit in federal court in Missouri, where he lives, alleging that the statement from the Kemner brief quoted by Montague was “untrue and libelous.”

In an amended complaint filed in 1992, Gaffey alleged as libelous Montague’s statement, “In fact, excess cancers have occurred, but it appears that the data have been manipulated to hide the facts.”

These two statements form the crux of Gaffey’s libel lawsuit. Under libel law, the plaintiff has the burden, in the first instance, of proving that the allegedly libelous statements are false. While Montague hopes, indeed, to demonstrate that the statements are true, he will be cleared of the charge unless Gaffey can prove they are false.

Journalists routinely rely on quoting government and court records as sources. Court records, in particular, are considered “privileged” information, and are extremely solid ground on which to build news reports. However, Gaffey’s suit draws much of its substance from the argument that Montague incorporated the views in those documents as his own, rather than merely quoting from the documents.

Montague’s saying “It appears” the data were manipulated is allegedly actionable as being Montague’s own statement of fact, rather than that of his sources. Still, in a case like this, in addition to demonstrating the falsity of the statement, the plaintiff also has the burden of proving that it was made either with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard for its truth or falsity.

Whether it is viable or not, one effect of Gaffey’s lawsuit was to silence coverage of Jenkens’ memo and the allegations of corporate fraud that it exposed. In the months following the memo’s release to the press, numerous newspapers in the U.S. and Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and elsewhere paid serious attention to the issue. The March 23, 1990, Atlanta Constitution carried a page-one article entitled, “Dioxin Research Attacked, EPA Says; Internal Federal Memo Accuses Monsanto of Manipulating Results.”

The March 27, 1990, Australian carried a story titled, “Agent Orange Case Papers Demanded,” reporting that the government was demanding the record of the Kemner case. Yet press coverage in the U.S. and abroad dried up once the libel case was brought against Montague. Even the suit itself has been covered only by alternative, specialized press such as Corporate Crime Reporter and Environmental Action, and has been ignored by the major media.

The Dioxin Story Grows

Industry and the media rely heavily on the three Monsanto studies on the Nitro incident when making the claim that dioxin is not especially dangerous. And, through repeated use and referencing, the studies have played a major role in creating the prevailing notion that dioxin is not the significant health threat that it was once thought to be.

In 1979, after Monsanto released information about the Zack-Suskind study, the Wall Street Journal published an article titled, “No Excess in Deaths Found in a Study of Dioxin Exposure” (October 23, 1979, p. 48). While the Journal quoted Monsanto officials, no other view was given on the issue of dioxin as a carcinogen. The full study was later published in the Journal of Occupational Magazine.

Shortly after the Zack-Gaffey study was published in Environmental Science Research in 1983, the journal Science published an editorial downplaying dioxin’s impact on health based on research done in the wake of several dioxin accidents. “Some of the accidents,” wrote editor Phil Abelson in the January 26, 1984, issue, “notably one in 1949, occurred long enough ago that were cancer to be associated with them, it would now be evident. Some 121 workers were involved in the 1949 accident, and while ironclad proof of a null effect is missing, so too is a basis for believing that TCDD is a dangerous carcinogen in humans.”

When Abelson’s views were challenged by a reader in a later issue, he pointed his audience to his sources in an editorial reply. One is a report by a panel charged to conduct a dioxin review by the American Medical Association (AMA). The AMA report, which was co-written by Suskind — a Monsanto consultant and a member of the panel — relied heavily on the three Monsanto studies. Another source was the proceedings of the dioxin symposium covered in Environmental Science Research, including the Zack-Gaffey study.

Three years later, Scientific American ran a major feature by Fred H. Tschirley largely downplaying the dangers of dioxin (February 1986). Writing about the 1949 Monsanto accident in Nitro, Tschirley stated, “The total number of deaths in [the exposed] group did not differ significantly from that expected in the population at large, and there were no excess deaths due to diseases of cancer or the circulatory system.” While Tschirley did not directly reference any of the Monsanto studies co-authored by Zack, Gaffey, or Suskind, the findings match exactly those in one of the Monsanto studies, which were the only retrospective studies done on Nitro workers.

With Science, Scientific American, JAMA, and the Wall Street Journal on board, it’s no wonder an entire religion has been based on the alleged safety of dioxin.++

11 thoughts on “Dioxin Critic Sued :: Monsanto’s William Gaffey vs. Peter Montague of the Environmental Research Foundation”