Originally published June 4, 2020 | Link to Original | See related letter | Alternative Photos (not published) | Read part one of this series

Dear Friend and Reader:

A few weeks ago hanging out in the backroom of 30th Street Guitars, master luthier Matt Brewster mentioned that the Woodstock festival was held during the Hong Kong Flu pandemic. All public sources agree that this outbreak of H3N2 influenza-A killed a million people worldwide and 100,000 in the United States between mid-1968 and 1970, during which time the festival occurred.

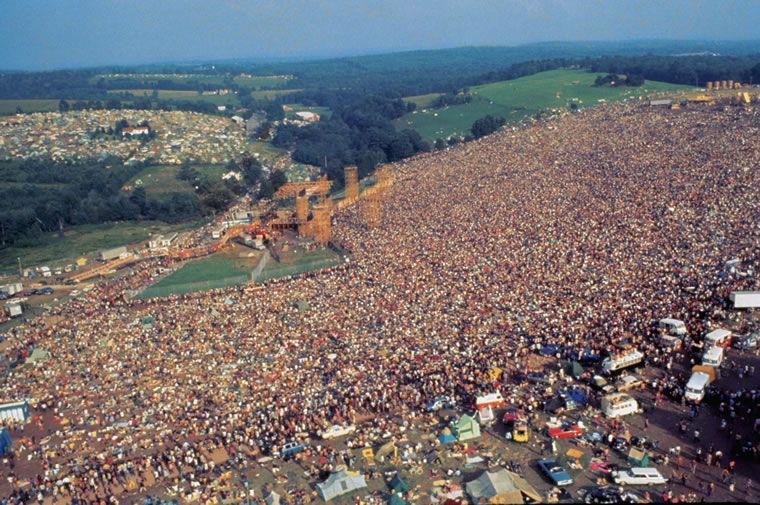

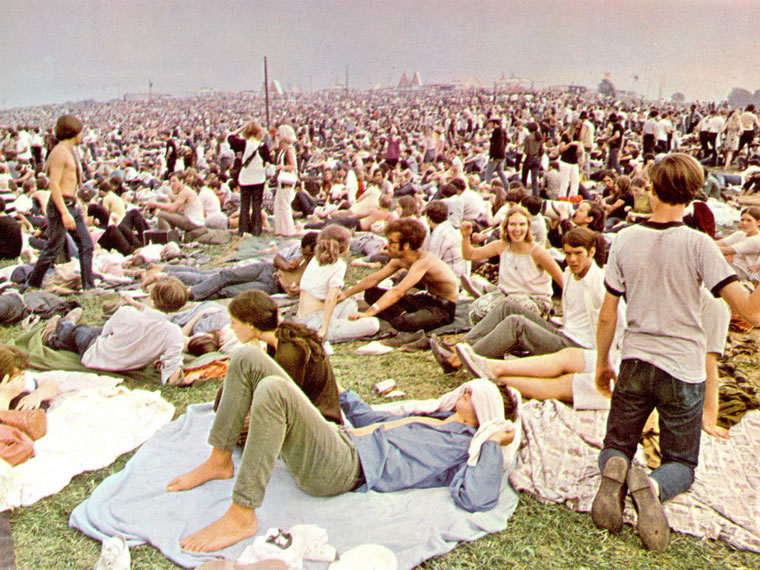

I posted a photo of the crowd to Facebook mentioning this fact, unaware I was wading into one of those seemingly pre-packaged, ready-to-snap shitstorms. My post got 157 comments, including a good few of the “there’s no comparison between then and now,” “you’re comparing apples to oranges” (about which I finally wrote an essay), “it wasn’t really in the middle,” and the “you’re an idiot” variety. People posted numerous articles “debunking” the claim from self-styled factchecking websites. Problem is, it actually happened. Even Snopes cannot make the whole Woodstock festival or a global pandemic vanish.

In that mysterious Facebook way, an audience of plebes spontaneously morphed into a panel of elite epidemiologists. They were quick to remind me that back then, more people smoked cigarettes and didn’t wear seatbelts, either. True, true. I knew that.

Not everyone thinks the way society has handled the threat of the “novel coronavirus” was responsible, helpful, effective or for that matter, even meekly sane. Not everyone thinks that living in constant fear or hiding in one’s home is a good idea, including and especially as a public health measure. That was demonstrated several weeks ago when we learned personally from New York’s Gov. Andrew Cuomo that 66% of new hospital admissions in New York City were people who had isolated themselves.

As for no comparison between Covid and H3N2, well, there was an outbreak going on that had already killed a lot of people, not just the potential for one. During this event, 450,000 kids packed onto a manure-infused cow grazing pasture, with thunderstorms much of the weekend — the perfect situation to “catch cold,” but the show went on, and history has not recorded even one person who got sick. Had social distancing been enforced, the festival site would have sprawled out to Pennsylvania.

Yes, there were some scientific differences between the pandemics — but not enough to account for the vastly disproportional responses: doing nothing, versus shutting down the culture entirely and pushing everyone apart from one another — for what was essentially the same type of issue. In this article, I will do my best to account for some of those differences.

Before I go on with this historical account of the 1969 Woodstock festival, its contemporary pandemic and the environment wherein they occurred, I would share this thought. Lest anyone take the message that a bunch of hippies from 1969 are encouraging bad behavior in 2020 (such as attending civil rights protests), my message to my readers is to take care of yourself. This includes thinking for yourself. There are many ways to bolster your immunity and your resistance to pathogens and toxins, which despite “freedom of speech” cannot be discussed openly. I have done my best to offer some ideas in the article Why You Need To Know How to Take Care of Yourself. Your neighborhood homeopath, naturopath or herbalist will have good information for you.

Was Anyone Worried at Woodstock?

There was a pandemic happening at the time of the festival. But was anyone worried? Were they all so very very brave, willing to risk death? In all my research into the festival over the years, I’d never heard mention of it even once. So I went to my trusted elders for guidance. Monday, I wrote to Bob Spitz, author of the definitive Woodstock history Barefoot in Babylon, and asked if Hong Kong Flu was a consideration at the festival. He replied right away.

“The short answer is ‘no’. But I have no idea what you are referring to.”

No idea, as in none at all?

Just to make sure, I drove all the way to Woodstock (the town, not the festival) to get my prepaid copy of his book at Golden Notebook on Tinker Street, which was offering face-covered, socially distant curbside pickup service. I asked that the book be sterilized, and that all references to sex, marijuana and LSD be edited out, but they did not offer that service.

The topic is not listed in the index; it goes right from “Holtzman, Jac” to “Hooker, John Lee,” without mention of Hong Kong, or Taiwan or Japan or the flu or anything.

So then I went right to the top, and contacted Michael Lang, who against all odds, dreamed up, founded and pulled off the festival. He emailed me and said, “It was not an issue then.”

Growing more perplexed, I thought I would ask an artist. They’re perceptive. My go-to was Elliott Landy, the official photographer who documented the concert from the stage, and backstage. Elliott knows me from my horoscope column.

Elliott wrote back an hour later. “You should know that neither my wife, who was there, nor I, ever heard of it at Woodstock.”

I consider professional photographers to be among the most situationally aware people I’ve ever met. They pay attention to everyone and everything. Elliott was in personal contact with the organizers, and mingling with rock stars and their managers all weekend. He would have noted concerns about a deadly pandemic. Never heard of it. Hmmm. Seems nobody had.

So Jerry Garcia wasn’t demanding you cover your face with a rag? Janis Joplin wasn’t telling her bass player to back off and not breathe so much? Melanie wasn’t insisting that you stay home and save lives? Pete Townshend wasn’t The Boy in the Plastic Bubble? Grace Slick didn’t want you to stuff a sock in your mouth? There were no plexiglass dividers in the hospitality tent? No influenza crisis area staffed by the Hog Farm? No electric guitar sanitizing stations? How the heck did everyone survive?

Pandemics Yesterday and Today

Despite current claims that we are experiencing The Very Worst Thing Ever, Hong Kong Flu was a significant global pandemic, as Covid is claimed to be. It was a problem beginning in July 1968, and would presumably be a serious problem in late August 1969, as influenzas come in waves. They’re also spread by droplets, as the “novel coronavirus” is said to be. Respiratory viruses are also believed to be spread by aerosols (dry particles), as Covid is believed to be. To my thinking, it would seem they are directly comparable.

In 1969, nearly all grandparents remembered the “Spanish Flu” outbreak of 1918, which killed an estimated 675,000 Americans in a much smaller United States, including many young people. The 1957-58 “Asian Flu” pandemic of H2N2 influenza-A was in the living memory of everyone at the festival. That killed between 70,000 and 116,000 Americans in a country about half the population as today’s — so for statistical comparison to today, we can double the death toll.

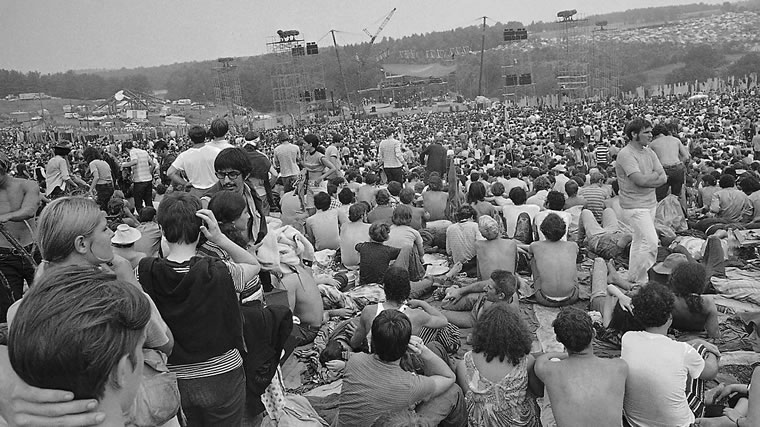

The concept of an “influenza” outbreak should have been deeply troubling. Yet as if nothing was going on, there were all those kids and young adults packed in together, commingled with mud, passing joints around, sharing beers and sandwiches and cans of Coke, many of them naked and hugging and kissing and having sex and even breathing the same air. Nobody even washed their hands, much less sang Happy Birthday twice while doing so.

Did anyone catch the flu? Does anyone know or anyone care? If they did, do they even remember?

Where the comparisons end, though, is that in 2020, world war was declared against a presumed virus, based on sketchy statistical death projections promising millions of bodies. Every school system, college and university was shut down. Every sports league has been shut down. Broadway went dark, as did nearly every theater in the world. Restaurants, bars, social haunts, shopping malls, movie theaters and brothels — all closed. Every 24-hour dive and diner from Portland, Maine to Portland Oregon, closed. And every concert, music festival and tour has been canceled. As far as I can tell, you can’t even have band practice many places.

The Megadeath Threat (and You Could Be a Silent Killer)

The initial estimate, first proposed by a Neil Ferguson of Imperial College London (later fired for violating social distancing rules), proposed that 70% of the world could get the virus, with a death rate of up to 3% (I have also read 7%, consistent with SARS). This was soon after repeated by Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor, which gave it real traction in the news. No serious doubts about these numbers were expressed. The worst-case scenario was sold and purchased at full retail value; more like extortionist rates.

In response to the threat of tens of millions of corpses, a series of stock market crashes in March took out 30% of the market’s value in advance of any problem manifesting in the United States. Right before Earth Day in late April, the price of oil fell below zero to about minus $30 a barrel due to lack of demand (the one bright spot in this mess, though not a good sign for the petrodollar).

Part of what led to the lockdowns was that people were informed they could be a superspreader. Yes, it could be you: just like that lady in Korea who almost killed her entire church! or the lawyer in New Rochelle who almost killed the whole synagogue! Anyone at all could become Smackwater Jack and shoot down the congregation — and not even know they were doing it. The new church shooter doesn’t need a gun, and could be you.

Kids were, and still are, being told they can kill their grandparents (or anyone) with a hug. There was a lot of hugging going on at Woodstock. This current paranoia is on the level usually requiring hospitalization and heavy medication, but it became normal and in essence mandatory to think this way. Just like nobody noticed the Hong Kong Flu at Woodstock.

What was the one certain difference between then and now? What could be behind such astronomically different responses to what was essentially the same thing? How about: in the 1960s, people were not so spooked by one another. In 2020, people acted exactly how they had been conditioned to become: terrified of everything. And how did that happen?

That Was Then. This Is Now.

Nobody at Woodstock had Instagram, Twitter and Facebook going off every 20 seconds, reminding them of the alleged body count and “case” count ticking up by the second, all but demanding that they be terrified and if not you’re insane.

There were no 24-hour cable news networks committed to driving up ratings, delivered to living rooms and phones, ensuring that everyone panic. Those news reports running around the clock, competing with one another, must present this as the greatest horror movie ever to come to life, or else what’s the “news”? Another boring pandemic just like the last one everyone forgot about?

In the Woodstock era, people were still aware of being physical beings, physically responsive to one another. They did not wake up and check their news feeds for instructions about what to think and feel. They were not electronically processed renditions of themselves, driven out of body by over-involvement in digital technology, afraid of one another, and mortified of physical existence. Everyone was not a presumed rapist or terrorist.

People were at a festival to have fun and to physically be together because that is what you did; there was nothing else. There was no such thing as doing something “virtually.” That was the whole point: to gather, in one place, for real — and be real; to feel the beauty and strength of being together, at the biggest combined peace sit-in and darshan ceremony in history.

They had real things to worry about, too, such as getting drafted into the Vietnam War and coming home in a body bag or without legs, or having to kill innocent people halfway around the world, and/or being sprayed daily with Agent Orange and dioxin. They were not in Vietnam. That became reason to celebrate. You can only do that when you know you’re alive.

The Case of the Viral Virus

What happened with the “novel coronavirus” is that the concept of a deadly virus went viral, in the age and medium of viral. It did so not only through droplets or aerosols but far more significantly, by spreading a panic at the speed of light through the extended central nervous system known as the internet. This network is extremely sensitive to fear-based thoughts and ideas. It’s a special place where even your oldest friends can turn into shrill assholes when they disagree with you.

For some reason, animosity, anger and fear are conducted through digital systems much more easily than friendly thoughts or beauty. People talk about the dopamine hit delivered when someone “likes” your post. The truly addictive internet drug is cortisol, the stress hormone, as stress has a way of reaffirming how stressed you’re supposed to be and why your anxiety is so important and helpful to the planetary condition.

Initial news reports spreading panic around the clock were rife with images of sickness, death and disaster; of emergency rooms and ambulances; of doctors and nurses either wearing environmental gear or complaining that they didn’t have any. These were relentless, horror-inducing and inescapable for anyone connected to the network, which is pretty much everyone, all the time. Troops of disinfectant-wielding soldiers dressed like the band DEVO were seen marching through the streets of every Asian city spraying some unidentified toxic chemical on everyone and everything.

Yet this problem is about far more than the content that is delivered by internet and digital television — it’s about what the communications conduits do to our relationship to ourselves, to one another, and to existence.

Newspapers deliver the news slowly; they are easy to ignore, and were even then in the Woodstock era, especially if there weren’t any around. You must go to them, find a quiet spot, and read reflectively. They are not available everywhere all the time. They do not lurch at you or vibrate in your pocket 100 times a day. The 1960s was the age of Walter Cronkite on Monday to Friday evenings for half an hour (originally, for just 15 minutes). He spoke to you in a calm and reasoned way, and went home. There were no TVs at Woodstock, and barely any telephones. Some newspapers got there, mostly for the purpose of organizers reading about their own festival.

Utterly Transformed and Distorted

Many times, I’ve quoted philosopher Eric McLuhan: “The body is everywhere assaulted by all of our new media, a state which has resulted in deep disorientation of intellect and destabilization of culture throughout the world. In the age of disembodied communication, the meaning and significance and experience of the body is utterly transformed and distorted.”

It was into this “utterly transformed and distorted” relationship to our bodies — cultivated and sustained over decades — that the concept of the “novel coronavirus” was inserted. It was not merely injected into a communication system. It was broadcast through a communication system that had already transformed people, pushing them further into disembodied experience.

That term is a fancy way to say paranoid, disoriented and irrational. Acting as if the reality of the physical world does not matter, or if it does, the only thing real is a pathogen that can kill you and nothing else matters. Acting like a ghoul or zombie. Or a mummy, wrapping one’s face in cloth, or a bank robber from the wild west, wearing a bandanna to cover one’s face.

Acting as if you have no idea who you are, or what is good for you — a state which would seem to facilitate instantaneous terror at the least threat, in a world where anything at all may be contaminated with a deadly virus. Anything except the bandanna you leave on the kitchen table.

We saw pictures of Italy: Milan emptied out, looking like the neutron bomb had gone off. The usually-teeming Spanish steps of Rome vacant of any people. Reports of so many deaths they could not bury the bodies.

Then just like that, it was gone. “In reality, the virus clinically no longer exists in Italy,” said Alberto Zangrillo, the head of the San Raffaele Hospital in Milan in the northern region of Lombardy in a May 31 interview on Italian public television.

That region was the most seriously affected in Europe, and now we’re being told that the virus clinically no longer exists there. Just like last week’s viral cartoon or cat playing the glockenspiel. Given that coronaviruses usually take 18 months to burn out, that’s a strange development.

Italy, so recently the horrifying epicenter of the crisis, has also rolled back its death toll, saying that 88% of those people had other illnesses and would have died anyway. In Sweden, which did not lock down, only 7% of the population tests positive for antibodies. In New York City, which did lock down, 20% of the population tested positive for antibodies. In England, so few people are “infected” that there may not be enough “infection” to test a vaccine.

This has not stopped England from banning visitors to one’s home, in effect, prohibiting sex with anyone but one’s live-in or spouse. Even that is being described as “high risk” behavior.

And as if that were not over the top enough, how about this advice from some medical professors at Harvard: avoid kissing, shower before and after sex, and even wear masks while having sex. “Abstinence and masturbation were ranked as ‘low risk’ sexual activities, while sex with people within a household, and sex with people from other households were ranked as ‘high risk’ activities.”

In their study, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the researchers, led by Dr. Jack Turban, wrote: “For some patients, complete abstinence from in-person sexual activity is not an achievable goal. In these situations, having sex with persons with whom they are self-quarantining is the safest approach.” Is it a surprise that the study was partly funded by Gilead, a company involved in manufacturing Covid drugs?

It’s time to study how this perverse, psychotic insanity passes for helpful or normal. Clearly, we are not in Woodstock anymore.

My observation after three months of total immersion in this issue is: If the medical establishment and government were really concerned about public health, they would advise people on the topic. They would take people off of medications now known to make Covid deadly. I remain curious how discussion of universal health care became discussion of one syndrome and vaccines for it.

Making the World More Like it was Already Becoming

At the time the coronavirus novel became a bestseller, the world was already socially distancing — through “social media.” Many were already sitting at restaurant tables texting others rather than conversing. Many were already spending more time on Facebook than with their families and their actual friends. There were public service campaigns featuring celebrities urging people to have device-free dinners. Presumably those ads were necessitated by a lot of devices at the dinner table.

Many people were already stuck at home with few social options, and only the internet to keep them company. Coronavirus rules have basically shoved everyone onto the internet for everything they were not already there for. It is astonishing to think that “going away to college” now consists of sitting in one’s bedroom and trying to study. The internet was already a viable way to avoid life experience. Now it is required. Colleges and universities still don’t know whether they’re opening, and some are considering becoming permanent remote learning institutions.

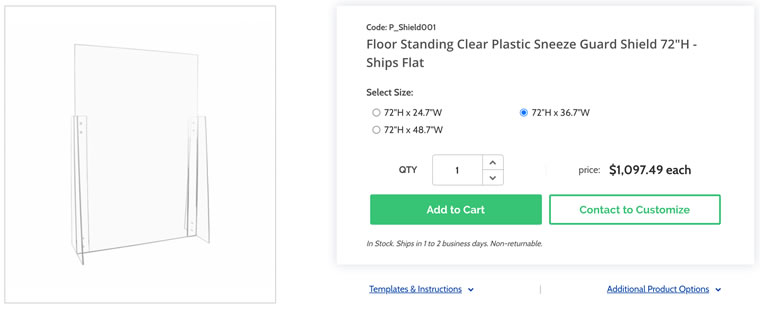

The physical world is taking on the same isolation. Now, everywhere you go, you see a new plexiglass barrier, “separating” you from someone. Given that viruses can go around things, this is purely symbolic, but it’s being accepted without question. Social distancing rules are still in place. There are little stalls and stickers on the floor everywhere. There are one-way aisles in many stores. Everywhere, people’s faces are covered and among many, there is a nervous, chilly quality in the air.

People who work with the public say there is a hostility present that reminds me of the callous way people treat one another on Facebook or Twitter. It’s a little like people have been transformed into the internet versions of themselves, cloaked by distance, fear and veils.

We are Being Trained by Robotic ‘Dogs’

Marshall McLuhan in his analysis of media effects noted that we become like our tools. Our tools are currently robotic. Very nearly every transaction in life is processed through a robot, meaning the artificial intelligence of the internet. We are therefore conditioned to be that way with everything we do.

Those are the mental patterns that we are taking on and emulating. This is usually an unconscious process, which includes adopting computing metaphors for all aspects of life. However, in case you want to be fully woke, some places are using robotic “dogs” to enforce social distancing. We are sure to see more robots doing the policing in the next few years. There are plenty of invisible ones being used.

Marshall’s son Eric, who lived through the computer age, noted, “At electric speeds, we, not messages, are sent. It is an old observation that on the phone or on the air you are in more than one place at a time, minus the physical body that you once used to define identity. The cybernaut abandons his body and physical identity and self (including gender) whenever he embarks on each trek into cyberspace. The conditions for disorientation are complete: out of body, out of time, out of space.”

We think people were tripping out at Woodstock. In fact, they were all there the whole time, hanging out with one another, the music and the mud. History has recorded not one single violent incident at that festival. Contrast with the supposed Woodstock revival in 1999 — the first “Woodstock” of the digital age (and the last ever attempted) — which was held on a fenced-in former nuclear bomb warplane base, which devolved into looting, rape in the mosh pit, and other hostility and violence.

When We Don’t Know Who We Are — And When We Do

The week I’m writing this, the lockdown has peaceful demonstrations that have degraded (or been pushed) into violent protests in many cities across the United States, ostensibly related to the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. That, in turn, evoked all the prior incidents of unarmed people of color being killed by the police.

It is easy to see this as the expression of frustration and a response to racial and social injustice. The background anger about the economic situation, which is disproportionally affecting people of color (as is Covid) is obviously present as well. Consider, though, that Marshall McLuhan proposed, “Violence is always a quest for identity.”

Identity is the very thing that has been destabilized in the world of digital immersion. It’s not that people waltz around saying, “I don’t know who I am. I forgot who I am. I need to search for my soul.” That would be tremendous progress. Ask any Buddhist monk. Notably, finding oneself was a theme of 1960s spirituality, and you hear nothing about that quest today.

Disembodiment includes unconscious loss of identity, which attempts to find relief in killing people, looting and riots. The police are suffering from the same issue; many are on a rampage of their own. White supremacists are also enraged, and seeking violent “solutions.” Everyone is affected by the digital environment, whether or not they participate directly (and nearly everyone does).

Human contact is perhaps the only thing that could satisfy the quest for identity prior to resorting to violence, so restricting contact with one another — and in England, making it illegal — is only going to stoke violent responses to life situations.

The Woodstock Festival, though not specifically planned as such, was a sane and healthy response to the violence and horrors of the Vietnam War. The thought of an equivalent “pandemic” as the one we are in now didn’t even cross people’s minds at the time. They were not afraid. They were bigger than a pandemic. They knew who they were or were on a quest to find out. People knew they had that option, and they used it intuitively. It was the thing to do.

This year, a war was declared against a “virus.” America loves to declare wars: on drugs, on cancer, on terror, on countries and on its own citizens. One way to view the participants of Woodstock was as refugees of America’s endless wars.

Now, in our time, the war has come home to the streets, by way of the internet. As Marshall McLuhan noted, “World War III is a guerrilla information war with no division between military and civilian participation.” What I find perplexing is that despite our communication tools, they are being used more to spread fear and spy on people than they are being used to offer actual information about how people can take care of their health.

“With Covid-19, the virus is delivered physically, but the much greater effects were delivered virtually via social media,” Andrew McLuhan, Eric’s son and Marshall’s grandson, said this week. “We may even be able to eventually say, regarding Covid-19, that not only did the effects precede the cause — the effect has vastly outgrown any biological cause. That’s a first, certainty on this scale.”

With love,

Planet Waves (ISSN 1933-9135) is published each Sunday and Thursday evening in Kingston, New York, Planet Waves, Inc. Core Community membership: $197/year. Editor & Publisher: Eric F. Coppolino. Web Developer: Anatoly Ryzhenko. Associate Editor: Amy Elliott. Assistant Editor: Joshua Halinen. News Editor: Spencer Stevens. Client Services: Victoria Emory. Illustrator: Lanvi Nguyen. Finance: Andrew Slater. Archivist: Morgan Francis. Technical Assistants: Cate Ryzhenko, Emily Thing. Proofreading: Jessica Keet. Media Consultant: Andrew McLuhan. Music Director: Daniel Sternstein. Bass and Drums: Daniel Grimsland. Additional Music: Zeljko. Additional Research, Writing and Opinions: Samuel Dean, Yuko Katori, Kirsti Melto, Amanda Painter, Cindy Tice Ragusa and Carol van Strum.