By Eric Francis

With Maria Henzler, additional research & translations. Reported from Erfurt, in the former East Germany and written in Munich in September 1998. This is part two of a series. Originally published in Rob Brezny's Televisionary Oracle magazine in Sept. 1998.

WE ARRIVE as the last few volts of daylight

By Eric Francis

With Maria Henzler, additional research & translations. Reported from Erfurt, in the former East Germany and written in Munich in September 1998. This is part two of a series. Originally published in Rob Brezny's Televisionary Oracle magazine in Sept. 1998.

WE ARRIVE as the last few volts of daylight drain from the late-evening sky. The vacuous, unlit, anonymous streets of the city are cobblestoned and narrow and one-way, jarring and agitating with that distinct 19th century medieval Napoleanic vibe, and we vibrate over the cobblestones in a crazy right-angled pattern searching for an eternity before we finally arrive at the tiny, as in two-room, hotel where we were expected hours before. East Germany. It still exists.

Looming over the city, as we rattle through the cramped and insidious back-alleys, jamming to sudden stops at dead-ends and getting newly lost every six minutes, are a pair of millennium-old High Gothic Roman Catholic cathedrals; not one, but two of them, lurking on a hilltop, with their many spires thrust black and angry against the backlit sky. And they are following us everywhere we go. It's worse than the shadowy images of late-night horror films. This is the living nightmare of art history students everywhere -- to be stalked by two Gothic cathedrals, as if it were the night before the final exam.

And lucky us, our hotel is right across the street from these divine masterpieces, right at the base of the hill. And when the bells, which weigh in at around 10 tons each, get gonging -- and they gong and clang over and across all the centuries at once, right in front of your face -- it is an experience of transcendental negativity; it is the sudden onset of nightfall in the broad afternoon. They are dark and mean and out of tune and it's just torture. And the monks up there

like to ring them. Sometimes it feels like it's never going to stop. One of these things, at 11.5 tons, is the oldest, largest, meanest free-swinging bell in the world. I would just love to take the clapper home for a souvenir.

Now, I too was wondering why there were a pair of High Gothic Roman Catholic cathedrals next door to one another, and it took a few days to get to the bottom of it. The Marian Dom came first. That was started in 1154, replacing the old Marian Church, which I guess fell down. Then in 1288, the local diocese had some saint's bones, those of St. Severus. Erfurt wasn't really in the district, but they wanted to keep the city in the fold, so they sent the bones over as a kind of marketing gesture. And what do you do with saint's bones? You build a cathedral, because every set of relics gets its very own. Government efficiency. And because it wasn't such a very big hill, the cathedrals are so close you can practically paint graffiti onto both at once. They are four meters apart at the closest point.

We have come here, of all the great vacation spots in Europe, following the trail of some black-and-white photos of a semi-nude woman taken on the sly in a tiny Roman Catholic church, and investigating the geyser of bullshit that erupted in their wake. [See Eric's report in

the August issue to catch up on the nudie-nun scandal.]

Germany is a culture where public nudity is just fine, but one where blasphemy still exists as a law. You can peel it all off and sun your privates on the banks of the Isar during business hours in downtown München, and not only do you not get arrested, nobody hassles you. Normal magazines display all kinds of nudity, on the cover and all. And one's first experiences on European beaches, Germany included, are filled with a kind of child-like delight owing to the exquisite array of breasts one can freely survey in the context of the beautiful women to whom they belong.

But Ewald Schadt, the photographer, is under criminal prosecution for committing

Beschimpfenden Unfug, "insulting nonsense" in a place dedicated to the worship of God. It's Adam and Eve all over again. As soon as God is around, you have to don the fig leaves. Our delving into the mystery school known as German law has revealed the astonishing fact that there are no real freedom of speech protections in the new Federal Constitution. Passed in 1948 and supposedly protecting everyone from the horrors and atrocities of the Holocaust that ended in the spring of 1945, the Brave New Constitution puffs out its chest and promises that "there shall be no censorship," but it also flatly guarantees protection of everyone's "personal honor" -- thereby creating a civil-rights loophole about the size of Siberia.

It turns out that the courts, if they want, can jail you for up to three years for saying or depicting just about anything potentially controversial on the subject of religion that doesn't come straight from the Bible or the

Academy Bulletins of the Bavarian Academy for Teacher Training. And Ewald's shots, for example, the one of his sensuous blonde model laying in repose upon the church's altar, right where the priest usually keeps the communion wafers and the cup of wine, that altar, clad in high-heels, black stockings up to her thighs and wearing some kind of lingerie on top, above which her fierce nipples leer outward, apparently did not qualify as kosher.

|

Photograph by Ewald Schadt |

It's Friday night, and tomorrow evening there's an opening of Ewald's other photography in an art gallery connected with the hotel/café where we're staying. Public exhibition of the infamous church shots is now strictly forbidden. But no sweat -- much of Ewald's work, the rest of which is so far still not contraband, explores that strange interzone where sex and religion converge, or perhaps from where they emerge. In one series of his photographs, a pair of nuns explore the delights of sado-masochism before the altar. In another image, a nude woman stands before an outdoor crucifix, seeming to be caught in the act of privately examining her nipples. Dangling above her head are the bottoms of Jesus's feet, nailed to the cross. It is mind-bending. Under German law, were it correctly applied, Ewald could probably receive several life sentences for his portfolio; were there a peace-time death penalty here, he'd be crucified upside-down.

We finally meet up with Ewald and our guide, Bernhard, and head over to Noah's Tavern, which has a little ark sticking out above the door. For a country that allegedly had no religion for 40 years, the place is dripping with it. I don't expect to be on the job so soon, just a few scant moments after enduring an unguided 10-hour safari of boondock Germany. The Autobahn was a sweltering parking lot for hundreds of kilometers, so we drove on secondary roads. In Hof, the last city of the former West Germany, it's clear that we're not in Kansas any more. In the west, in places like Munich and Freiburg, really, everywhere, civilization is meticulously maintained. Buildings that went up in 1621 gleam in the sun, adorned with pots of absolutely perfect red flowers in every window, and seem to pop off the pages of

Richtiges Deutchland magazine. Everything, flower pots included, was just painted, taken apart and repaired last week or last year at worst, every door hinge is oiled regularly, the streets are swept and washed, and you've never seen anything so quaint in your entire life except maybe the Germany exhibit at Epcot Center.

And if you're hungry, there is a terrific variety of food: bratwurst, knockwurst, fleischwurst, bloodwurst, tonguewurst, ziegewurst, liverwurst, weinerwurst and weisswurst; in short, the best wurst anywhere. And bread. Each bite of the bread is a solid meal in itself.

But here in the east, on the other side of the old Iron Curtain, the candy-coating seems to have been cracked off of reality. In fact, it never went on. In the cities, many buildings are ancient and unmaintained, and there are abandoned ones and even empty rubbly lots. The vacant streets look like somebody dropped the neutron bomb, that clever nuke that eliminates the pesky people and leaves the buildings in good working order. Nazi architecture stands in all its glorious Goulden's Spicy Brown mustard-yellow splendor, all the dingier for collecting half-a-century of coal grime and car exhaust, alongside which are erected assorted architectural travesties of the old East Germany, the DDR, mixed in with everything else built from the Middle Ages to the 1940s -- everything, that is, that survived some of the most thorough precision saturation carpet bombing runs in history. Maria explains that after the war, the DDR couldn't afford to rebuild or even clean up in some places. So it was as if time had frozen, and East Germany became a huge time capsule, sealed in from the rest of the world like an ant farm. When the reunification came in 1989, they finally started collecting the debris in some places, throwing away their plastic cars, and building a modern nation.

In the rural areas, tiny little towns appear just like they looked on May 9, 1881, a day when nothing much happened. The whole place exudes that distinctive "where in God's name are we" feeling from every corner.

But one good thing is that in the east, they've discovered rock and roll. I have never been more music-starved in my life than these five months in Germany. We walk into Noah's Tavern, past one of Ewald's images on a poster announcing his opening the next night. It features the nude torso of a beautiful young woman, upon one of whose breasts has been painted an intricate puzzle design, gazing out innocently, and she's towering over the spires of a cathedral -- an Ewald Schadt classic -- and as we walk in and sit down, Bob Dylan plucks and brays across eternity:

Now at midnight all the agents

And their superhuman crew

Come out and round up everyone

Who knows more than they do.

They bring them to the factory

Where the heart-attack machine

Is strapped across their shoulders

And then the kerosene

Is brought down from the castles

By insurance men who go

Check to see that nobody is

Escaping to Desolation Row.

In Germany it's hard to get anybody to talk honestly about the Holocaust. One of my missions in coming here was to find out how it happened, how so many tens of millions of people were arrested, imprisoned, shot, tortured, gassed and cremated, just like that; how it went on and on for years, ending with a massive, morbid free-for-all in the final months when the SS knew it was over. I did not expect to interview some retired old Gestapo guys for the "inside story," but rather, I thought it might be possible to discover something in the culture that would help explain it. When I raised the subject, people would often look at me sheepishly and tell me how ashamed they are of their country's conduct, but fortunately that's the past. And yes, we learned all about it in school. But that's about it. Not a shred of the cynicism you'd expect to see. No anger. Just, you know, sorry about that, it was terrible, let's have lunch. But Bernhard, who says he's one of 40 Jews still living in Erfurt -- his mother was a Jewish concentration camp survivor -- has a little more to say.

A writer, artist and political activist born here in Erfurt and raised entirely under the DDR, he began documenting Nazi crimes at the age of 18 in 1968, the same year Russian tanks rolled across nearby Prague and blew everyone's mind, and the year he sat in jail for six weeks under "protective custody" for playing music at an anti-Soviet demonstration one afternoon. His speaking voice rings deep and thick like those 11-ton bells up the hill wish they could. He starts right in with something that is quite unbelievable.

An abandoned lot behind apartment houses on Feldstrasse, in Erfurt, in the former East Germany. This was the location of one of the earliest concentration camps, called a 'protection arrest camp,' located directly in the center of hundreds of private residences.

The Holocaust, he says, began right here in Erfurt, where the first concentration camp, or

konzentrationslager, was put into a dense city neighborhood quite early on. "Some people were killed there," he explains, but mostly they were interrogated and tortured; one of the favorite Nazi torture methods of the early days was hanging people from poles by their arms, which were tied behind their backs. "People said they heard cries and screaming. They needed one pillow more for the night because people were shouting down there. It was an old factory in the middle of these houses where this happened, and everyone that lived on the first floor could directly look into this concentration camp." The infamous Buchenwald, which he says is about 20 kilometers away, came a few years later.

I have seen a lot of images from the Nazi regime, because as a student I taught at the Holocaust Education Center in John Dewey High School, in Brooklyn. But a concentration camp in a city neighborhood? I asked the journalistic Dumb Question of the night: Why didn't people do anything?

"Because they thought it was right. Because everything that the law says is right. And people still think that way. This is proven, because how can a totally communist country become a totally capitalist country in one day? If the country were to become communist again, everybody would become communist. If it were to be fascist, everybody would be fascist."

Yet Erfurt, in particular, has a reputation for dissent; if you're fishing for dissidents, look where there are a lot of reactionary arch-conservatives. A major city, I learn that it was where Martin Luther, the white one, attended seminary, and where he launched his tirade against the Roman Catholic Church, writing, in a 1517 letter, "These unhappy souls believe that if they buy a letter of pardon they are sure of their salvation; also that souls fly out of purgatory as soon as money is cast into the chest." Ooooch. One of Luther's position papers, on which he demanded public debates, inquired of Church authorities, "Why does not the Pope, if he has the power, out of Christian charity, empty purgatory of the suffering souls all at once?" Ouch.

Now a Martin Luther doesn't come strolling along every day, but Erfurt maintained its reputation, its kind of freaky-and-free-despite-it-all vibe, and some say that's why Hitler -- in addition to his National Socialist (Na-Zi) party being strong in Thüringen, the "green heart of Germany" -- chose Erfurt to begin the rounding up of political dissidents, anti-Fascists, priests, artsy-fartsies, what were called "work-shy" people, and anyone else who potentially threatened him. He was obviously insecure. It's clear that once Adolph and his boys had their foot-holds in place, kicked with steel-toed boots into the absolute destitution of the German economy and the grave desperation of its people in the early 1930s, the idea of "public support" became rather negated by public terror. In other words, say or insinuate anything against the Nazis and you're off to Buchenwald, blond hair and blue eyes notwithstanding. And many millions of people were arrested and murdered for far less. So dissent was not what you'd call a major factor in the early years, and effective organized resistance finally came much later.

Back to our main story: I don't think that what happened to Ewald Schadt, that is, the cops coming into his house and taking away his nude church pictures, is the worst civil rights violation in all of human history. It is disgusting, it has a kind of Gestapo vibe and the fact that the church was behind it is sickening. But personally, I was more freaked out about how casually people here took it when I told them the story, even copping the attitude that well, if a nude woman in church offends people, they have

a right not to be offended and so the cops should

do something about it. And my position was, keep thinking like that, and you're just inviting back in the worst of all karma, which I imagine they would have had enough of by now, all things considered. My position was and is that those pictures are a clear social and political statement, and therefore a form of dissent, and dissent, more than anything, needs to be the single most protected thing if you call your society free. Especially, needless to say,

Deutchland über Alles. But if I discovered one thing here, it's that I've got some American blood.

Saturday night arrives and Ewald's opening begins and the gallery upstairs starts filling up. The crowd is a sampling of the Erfurt intelligentsia, employed, intent, smart-looking people, all about 40ish, nobody saying so much, just taking it in, all with the college-grad little silver-framed glasses and a little gray hair and hands-in-the-jeans-pockets look. It's high summer and some of the women are in simple dresses. Everyone is standing amid Ewald's work, poking around, exploring his shots of women in places like grain factories and steam-pipe rooms and so forth, all done with a strange swirly effect he creates by his smearing the developer onto the prints with his hands.

My personal favorite shot is hanging near the stairs, one from the nudie-nun series. It portrays a pious Sister standing in front of a gothic-looking brass candelabra, reading aloud from an ancient huge Book of Old, which is laid open across one of her arms. Her floor-length habit is open, unzipped all the way down the front, and she wears her clerical blouse and collar. Follow a line upward from her feet, up her black leather boots, which are exposed by the open front of the habit, go up, and up, and up to the top of the boots, which are about eight inches above her knees, and of course one's eyes cannot help but keep going, and there before you, looking at you, is her shaved vulva. Meanwhile, as if you didn't notice, she keeps reading aloud from her book.

The program begins with our guide, Bernhard, reading a little erotic literature to warm up the crowd. He recites with that basso-profundo rolling out from behind his enormous mustache. He looks like the archetypal proletariat. Ewald sits next to him in some kind of elk or buckskin pants and with one of those cowboy shirts with snaps and rivets all over it, with his arms folded. Bernhard is reading some old s/m stuff; it's in German of course. He goes on for a while. Maria whispers in my ear what's happening, and it starts kind of sexy and then suddenly, as it continues, everyone is being treated to a graphic description of the experience of a guy being strangled to death whilst he watches someone fuck his wife, and it goes on and on like this for forty-five eternal and never-ending minutes, in the middle of which someone starts playing guitar in the background for a theatrical effect, and the people, all the ones here who are hip and unorthodox enough to come out to something like an erotic art opening, are just standing there with their faces dull and frosty-white deciding, one by one, not that it's weird, not that they may be in the wrong place, but they are absolutely without question in the wrong place.

It is a short-lived event. When Bernart finally ends his presentation, and after Ewald says a few words, it was like someone had opened a canister of C-S gas and the place evacuated, without cash changing hands, no pieces sold, no books sold, no prints sold, and it's lonely -- the only people left are the nude nuns and the owner and a few friends, and now the owner desperately wants me to interview her. She insists. It's her time to Face the Nation.

I bring over my microphone and notebook and do my duty. She is, I learn, pleased with herself for having staged this radical event, and, not only that, right across the street from The Marian Dom and St. Severus to boot! To her, this is the Ultimate Statement against those monsters, and she's pulled it off; she has sinned, and behold, she has not gone to hell. It is vividly clear from what she says, that, if nothing else at all has happened this evening, she has at least accomplished one thing: maintaining her reputation as someone who is not afraid have a reputation. It is quite a depressing night.

Early afternoon Sunday and we're going to meet Bernhard for a tour of some Nazi artifacts. Two o'clock comes and we walk a few blocks. First he takes us to what remains of the old Erfurt synagogue. We explore the gutted building, and I wonder what they said to one another here during those years. Then we ride a streetcar across the cityscape, and then another, toward a place called Ilvers Gehoffen, which is now part of Erfurt but a century ago was its own town, and we get off the trolley and walk, stopping to peek into the apartment house where Bernhard was born. He said he hadn't been back here since the late 60s when he was investigating Nazi atrocities. The neighborhood has that neutron bomb feeling.

|

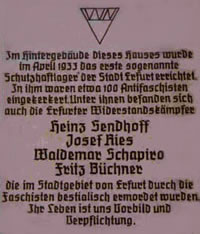

Plaque on Feldstrasse, Erfurt, in the former East Germany, dedicated to four murderd anti-fascists in the Erfurter Resistance Warriors who were imprisoned here in April 1933, less than three months after Hitler took office. At the bottom of the plaque is the inscription that 'Their lives should be an example and obligation to all of us.' |

We come to Feldstrasse, an ordinary-enough looking depressed urban street, with a row of small apartment houses. The neighborhood reminds me of somewhere in the desolate Bronx. In the middle of the block, on the front an apartment building, between two first-floor windows, is a memorial plaque, informing rare passers-by that on the other side of these buildings was a "protection arrest camp" where 100 anti-fascists were imprisoned, tortured and interrogated, and where in April 1933 four leaders of the "Erfurter Resistance Warriors" -- Heinze Sendhoff, Josef Ries, Waldemar Schapiro and Fritz Büchner, were imprisoned and, somewhere -- it's unclear where -- "killed like animals." This was less than 12 weeks after Hitler took office. We are aghast at the swiftness of this. There is a big garage door near the sign leading under the apartment houses and into the warehouse on the other side, which is now occupied by a metal company.

We walk around the block to the right, and behind the row of houses is a large and mostly-vacant city lot. There are a few dilapidated buildings and a lot of old bricks lying around with weeds growing. The metal company's building is behind a fence; there's also a brick building that looks like an old slaughterhouse you might see along the lower west side of Manhattan. This was it, this whole place. We are standing in what we believe was the very first Nazi concentration camp.

Normally we are used to seeing the terrible results of the Holocaust; these are the humble and all-but-forgotten beginnings. I doubt whether any other Americans have come here. The warehouses are indeed surrounded by numerous apartment buildings. Bernhard explains that there was an exercise yard for the prisoners, which we are now standing in. And here, he said, as we walk, was a very popular cinema where the good citizens would watch movies right next door to where prisoners were being tortured. We ponder this one for a while. At a little café across the street from the ruins, the Marmara Imbis Turkish Bar and Café, people are drinking coffee on the street.

The psychology becomes very clear. Put the thing where everybody can see it and hear it. And naturally, nobody will complain. And if you lived in one of these apartments, on a hot summer night when the windows were open, you certainly might want another pillow to bury your head. As we walk around surveying the scene, taking photographs, faces start to appear in those windows and eyes stare at us. I know that they know exactly why we are here, and the way they are gawking at us their anger is clear. We are acknowledging what they must somehow both deny and yet live with every day of their lives. Nothing changes here.

We walk to a street car and head back to the hotel. I don't know it at the time, but I am slipping into shock, and it will be some weeks before I come out of it.

An hour later, Maria and I decide to take a walk. More discoveries await us. Across the street from the hotel, next to the pair of High Gothic cathedrals, is another hill, a higher one, with a wall on top, and we're going to take a look at what's up there. The hill is called the "Zitadel of St. Peter and St. Paul." It is a compound; the wall is new, we learn, built around 1700 after it was temporarily conquered by some guy named Johann Phillipe von Mainz in 1665. We pass through an archway with several layers of iron gates, the kind that can chop you in half or spear you with inch-thick spikes if they slam down on you. The structures are made of granite blocks like the ones in Grand Central Station. It is an actual citadel; clearly Johann would not be back.

We are now inside this, I don't know, this

environment. It's different in here, and we start to look around. At one side are some crumbling wooden buildings that look about 75 years old. We creep around the back spaces, astonished. The feeling is just dark. The feeling is

anything could have happened here and probably did.

In the back, behind the decaying wooden buildings, we find a few ancient stone tunnel-ways leading down to somewhere covered by locked, black iron grates. And then we see a strange thing: a man in a monk's robe, hooded and carrying a torch, leads some people down one of the tunnels. We watch as their torch-light slowly disappears around a corner and down into the Earth. These passages apparently lead back to the two cathedrals.

From here, we walk between some buildings, through a kind of back alley, and it feels like the abandoned back yard of the Third Reich. We come out at the other end and there is a stone building with a tiny sign informing us that it was a

kreigsgericht, a wartime court for capital tries -- death penalty trials -- under Hitler. There is some relationship between the Feldstrasse warehouse camp and this place and Buchenwald, which opened in 1937, but it's not clear what the relationship is at first. Anyway, Buchenwald is at this point a vague notion, something further out on the horizon and impossible to conceive of.

I have been to many eerie places in my life, particularly to the scenes of environmental catastrophes, and this is the feeling. It's a disaster zone. It looks normal. It's neat and clean. But there is something invisible in the air and you've got to be dead not to feel it. It's clearly a very old place. There are two other main structures up here. One is a now-abandoned church, really a little stone cathedral, that was begun in 1104. For many years this was the biggest and most beautiful church in the region. The other is an enormous military-looking structure made of brown stones, three stories high, that was built by Napoleon, who was one of the many conquerors over the centuries, and who used Erfurt as his central organizing point for Eastern Europe. These buildings were also used by the Nazis. Again the feeling comes on:

anything could have happened here.

The desolation is interrupted when we see the guy in monk-robes again, and then a third time, and now he's not with his guests. I introduce myself. Maria has to translate. His name is Brother Hajo, and he knows the history, and he's willing to talk to us for a while. The stone church, which was started in 1104, was part of a Benedictine monastery for women founded in 836. A guy named Bishop Bonifacius built the first church on this hill in 742, a church constructed of the wood of the sacred tree where the nature-god Wodan was worshipped for countless centuries. This was what old Bonifacius, a traveling Irish bishop, did for a living: he went around on his missionary work chopping down sacred trees, informing the people that their God was dead, but not to worry, that there was another God, thus converting the local Pagans to Christians. Hajo says somebody finally killed him.

But the key date in this Zitadel's history, as far as I am concerned, is Feb. 8, 1933, just one week after Hitler assumed office as Reichs Chancellor, on Jan. 30, 1933: the day when the most awesome missionary of all took over the government, hoisted up his broken cross, and the citadel became the first

konzentrationslager. Here it began: the place where the earliest prisoners of the Reich were taken, political prisoners mainly, prisoners of conscience, locked inside the Zitadel of St. Peter and St. Paul. Very few lived to tell the story.

Tomorrow we go to Buchenwald, a small city built by the blood of its own inmates a few years later, carrying out the same traditions, with the SS imprisoning and murdering people for what they said, for what they believed, for their political ideas and photographs and religious convictions, only on a scale you cannot imagine, and the sight of which nothing in this world can prepare you for. But now: Now it's time for coffee. We hike over to Noah's Ark and drink a few cups and talk about life and our relationship for a couple of hours, and it's a nice warm night when we come out and walk back toward the cathedrals. But something is different.

We hear music. It is a live orchestra, with the timpani drums bouncing off the cathderal walls. And the behemoths are illuminated, blazing blue and red and green, and the steps leading to the things are now a huge stage, covered with cloth, and set before it are grandstands and an audience of several hundred people. There is a woman in a vast gold dress, and it's the grand finale of

The Fairy Queen by Leonard Bernstein, pouring out to the whole place with its gusts of love and celebration through the ancient darkness.